The National Research Council, the first and central piece of Canada’s federal research effort, has played a key role in the development of world-changing inventions. But after a tumultuous few years that saw a shift in its mandate, the NRC faces another evolution in its role, Ivan Semeniuk reports.

In a week dominated by news from the battlefields of Europe, few were paying attention to a small committee signed into existence by the Canadian government on June 6, 1916.

Known officially as the Honorary Advisory Council for Scientific and Industrial Research, the nine-member group of academics and industrialists was tasked with marshalling the scientific and technical capacity of the nation.

There was only one problem: There wasn’t any.

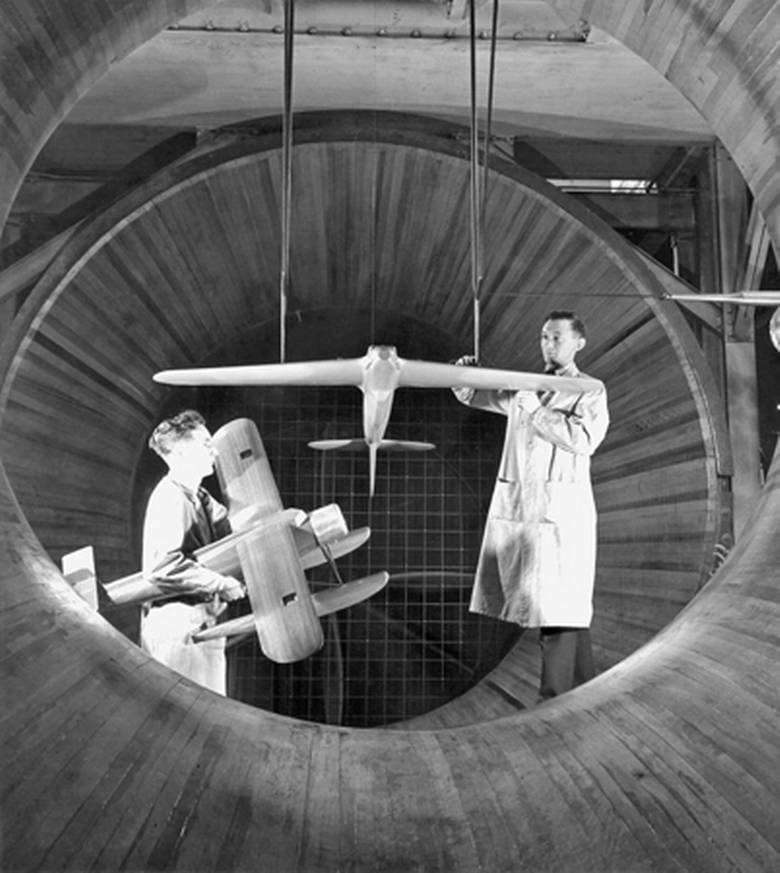

Scientist study aerodynamics in the NRC’s first wind tunnel, built before the Second World War. NATIONAL RESEARCH COUNCIL OF CANADA

What followed, over the next several years, was the group’s evolution into the National Research Council, the federal government’s own research and development enterprise and, in many ways, the foundational core of a national science culture in Canada.

One hundred years later, the NRC is still with us in a vastly expanded and very different form. With an annual budget of $1-billion (four-fifths of which comes directly from the federal government), it is a coast-to-coast enterprise with about 50 research facilities and institutes across the country. Its nearly 4,000 employees, divided among scientific, technical and administrative staff, work in areas as diverse as astrophysics and human health. Along the way, it has fostered inventions, nurtured Nobel Prize winners and provided a home to some of Canada’s most creative and unsung geniuses.

Yet the NRC’s role in a changing global research landscape is far from secure. The organization’s past few years have been among its most tumultuous, following a shift in mandate that saw its resources more directly aimed at serving Canadian business. The president that led that transition under the previous Conservative government is now on leave and a planned reorganization is in limbo. With its future leadership and guiding vision on the table, the NRC is now facing the prospect of another evolution in its role, within the Liberal government’s yet-to-be-unveiled innovation agenda.

Sources close to the government say that there is no doubt the NRC will be part of the plan and that Ottawa is on board with the idea that the organization needs to have a foot in both basic research and applied science in order to be an effective catalyst for innovation. The latest federal budget bolsters the NRC’s Industrial Research Assistance Program, which provides advice and support to small and medium-sized businesses doing industrial R&D – an activity where Canada lags, according to international indicators.

But exactly where the NRC will fit in as Canada responds to global challenges such as climate change, public health and security remains an open question.

“NRC has done well when it has evolved – when it’s looked at the context and understood that it might well have to change,” said Janet Halliwell, a Victoria-based consultant on science and technology policy who once worked at the council

She is among those who argue that the government still needs its own research entity to perform functions that no university or industry lab would.

An obvious example is the research that underlies national construction and engineering standards – a role the NRC has played since the Second World War. Another would be large-scale testing facilities, such as a wave-making system recently approved for a facility in Newfoundland to evaluate the performance of marine vehicles and structures in heavy seas. The NRC also serves as a natural point of contact with the science agencies of other countries on research efforts that may require international collaboration.

After a blossoming during the postwar boom, the NRC had an enormous footprint that touched virtually every avenue of Canadian research. In the decades that followed, it helped mount major efforts in experimental science, such as the Sudbury Neutrino Observatory, and launch Canada’s share of the Internet. Its facilities also proved crucial for commercial applications, from high-performance speakers to computer animation.

The Falcon 20 is the world’s first civil jet powered entirely by biofuel. Research experts at the National Research Council will analyze this information to better understand the environmental impact of biofuel. NATIONAL RESEARCH COUNCIL

Both Atomic Energy of Canada Ltd. and the Canadian Space Agency began as spinoff branches of the NRC. So, too, the medical and natural-science-based granting councils that today fund most of the university-based research in Canada.

But this budding-off of functions may have had an unintended side effect by making the NRC’s role less clear. For most of the lifetime of the baby-boom generation, the council’s best-known function was as keeper of Canada’s official time signal, broadcast daily on CBC Radio. Beyond that, its various roles and projects across many fields of research with varying degrees of connection to industry, academia and other government departments have made its role harder to see and understand.

Dick Bourgeois-Doyle, the council’s secretary-general, said he was surprised to learn, soon after he joined the organization in 1987, that it was NRC scientists in Halifax who took on the public-health crisis that erupted when toxic mussels from Prince Edward Island killed three people.

“These guys were working 24-hour days, sleeping on cots and living off pizza, trying to solve this issue,” he said. “I thought I knew the NRC.”

Since then, the scope and quantity of university-based research in Canada have expanded, which has led some to question whether the NRC is still relevant.

But if there were no such entity, the government would probably have to invent one in order to have a handle on what kind of emerging science might be useful for solving national problems and supporting industry, said Paul Dufour, a science policy analyst in Ottawa.

“You need to have that in-house to be able to assess the validity of the knowledge that you’re using,” he said. “Basically, it’s the ability to have a crap detector built into your research base.”

NRC’s greatest hits

EARLY DAYS

One of the NRCs early accomplishments was to develop a wheat strain that eliminated the damaging fungus, wheat rust. NATIONAL RESEARCH COUNCIL CANADA

Science and technology in service of a growing nation was the core preoccupation of the Honorary Advisory Committee for Scientific and Industrial Research, established in 1916 and soon to become the National Research Council. Early projects reflect the nation’s agricultural and resource-based economy, including the effort to develop crops with resistance to wheat rust, a damaging fungus responsible for a significant loss of production at the time. The council also oversaw a program to turn lignite, a low-grade form of coal mined in Saskatchewan, into a viable fuel source for heating, rail transportation and generating electricity. In 1920, the NRC pioneered the development of aerial photography in Canada by improving ways of keep airborne cameras steady while in flight. It also successfully tackled the problem of discolouration in canned lobster, which aided the Maritimes fishery. In 1929, the council launched the Canadian Journal of Research, the nation’s first peer-reviewed scientific publication, which later split into several different journals.

GOING TO WAR

The ‘Night Watchman’ radar instillation ay Herring Cove, N.S., was the first coastal-defence radar system. NATIONAL RESEARCH COUNCIL CANADA

The NRC came into its own with the opening of dedicated laboratories and research facilities during the 1930s, and an acceleration of efforts to prepare Canada for modern warfare. Its first wind tunnel was built in Ottawa at the request of the Department of National Defence. Among other projects, the tunnel was used to study the aerodynamics of aircraft skis. Scientists were brought into the NRC for a range of military-related research, from developing fabrics and gas masks to protect soldiers from chemical weapons to working out ways to prevent German mines from magnetically sticking to the hulls of Allied ships. After the outbreak of the Second World War, Donald Hings, creator of the first walkie-talkie in 1937, was asked to redevelop his invention for military use. The NRC supported the development of the first G-suit for pilots and also devised the first operating radar system in North America, called the Night Watchman, which was deployed at Herring Cove near Halifax in July, 1940, for coastal defence.

BOOM TIMES

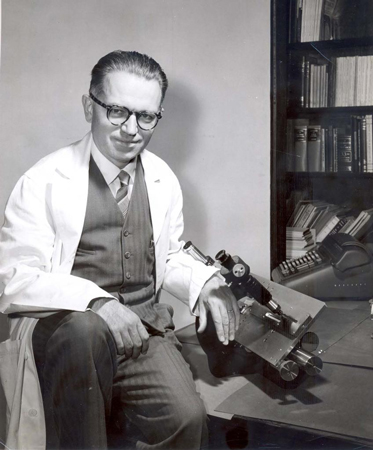

Hugh Le Caine, a pioneer of electronic music, with the Sackbut, the first voltage-controlled synthesizer. NATIONAL RESEARCH COUNCIL CANADA

During the postwar boom, the NRC was the powerhouse of Canadian research and development, spawning technical innovations across a wide range of fields. The period saw the development of the crash position indicator, a radio beacon for downed aircraft that was the precursor to the black box. In 1951, researchers working with the University of Toronto’s Banting Institute developed the world’s first external heart pacemaker. Research at NRC also aided the development of canola, now a multibillion-dollar crop, the construction of the St. Lawrence Seaway and the engineering behind the Avro Arrow fighter jet. This golden era in the NRC’s history was personified by creative inventors such as George Klein, who built the first practical electric wheelchair, and Hugh Le Caine, creator of the Electronic Sackbut, the forerunner of the music synthesizer.

SUPERSTARS AND SHIFTING PRIORITIES

Originally from Germany, Gerhard Herzberg fled before World War 2 and spent 10 years at the University of Saskatchewan. He spent three years at the University of Chicago before joining the NRC in 1948.

NATIONAL RESEARCH COUNCIL CANADA

The NRC played a role in the careers of several Canadian Nobel laureates, including Gerhard Herzberg, who won the prize for chemistry in 1971 for research into the structure of molecules. Dr. Herzberg was one of a number of superstar scientists whose work came to fruition at the NRC and who helped to build an international reputation for Canada in science. Others included Keith Ingold, known for his work on free radicals – chemicals associated with the aging process in animals – and Harold Jennings, who in 1982 patented an effective vaccine against meningitis C suitable for children as well as adults. It was during this era that university-based research became an increasingly larger part of Canada’s science effort, and the NRC hived off its role as the primary funder of academic science, while still supporting “big science” facilities, such as astronomical observatories. Fluctuating budgets began to take a toll in the eighties and nineties even as the council established new centres to advance research in focused priority areas such as fuel cells, nanotechnology and environmental toxicology.

21ST-CENTURY REDIRECT

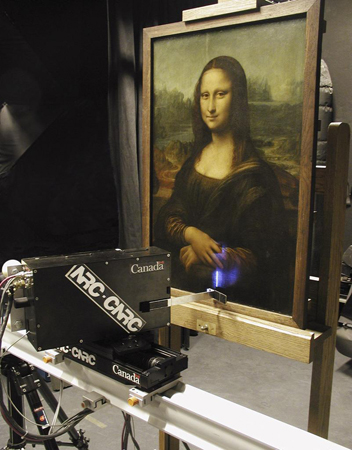

In the early 2000s, the NRC continued to gain worldwide attention with some of its technical advances, including Paul Corkum’s work generating the shortest-ever pulses of laser light to capture high-speed processes in molecules. In 2004, 3-D imaging technology developed by the NRC was used to scan theMona Lisa to reveal details about Leonardo da Vinci’s painting technique. In 2012, the council flew the first civil jet aircraft powered entirely by biofuels. But with the research landscape diversifying and the economy under pressure from globalization, the NRC’s evolving role in national research has also been the subject of scrutiny by successive governments. The Industrial Research Assistance Program, launched in the 1960s as a way to support research in Canadian industry, has grown in prominence. In 2013, a controversial change of focus under the previous Conservative government was aimed at making the NRC an industry-facing provider of research services. Early indications from the current Liberal government, which is preparing to launch a new innovation agenda for Canada, suggest further changes are in store.

IVAN SEMENIUK

Science Reporter The Globe and Mail

Last updated: Tuesday, Jun. 07, 2016 7:50AM EDT