High demand for counselling is changing how Canadian campuses get students the help they need – but many still feel they’re falling through the cracks.

Julia Burnham knows the symptoms well: a simple stop in a busy coffee shop or crowded bus ride can prompt the sudden, frantic feeling that she can’t get enough air. For years, she has suffered from full-body anxiety attacks that can leave her sobbing in a workplace bathroom, or urgently seeking the safety of her bedroom. A numbing depression follows, which can keep her housebound for a day or two.

The fourth-year university student may seem like a perfect candidate for school counselling services – the kind that postsecondary institutions have been offering for more than 60 years. But in fact, with her multiple diagnoses of post-traumatic stress disorder, panic disorder, social anxiety disorder and major depressive disorder, Ms. Burnham is exactly the kind of student that many universities now try to refer to resources outside of their counselling centres.

For the past three years, Ms. Burnham has been paying $120 a visit to an external Vancouver psychologist – rather than relying on services University of British Columbia students can access without charge. (Counselling services can be funded in part by annual student fees.)

The number of young people seeking mental-health help, in Canada and worldwide, has been rising for years, and the phenomenon is stretching school resources. Under the strain of appointment gridlock, student criticism and, in some dire cases, suicides on campus, postsecondary institutions are rethinking their strategies to handle the mounting need. At UBC, that has meant a new-found focus on referrals. By taking students with more enduring needs out of internal counselling, the thinking goes, more students can be seen by the school team, and those who require more complex support will get the help they need.

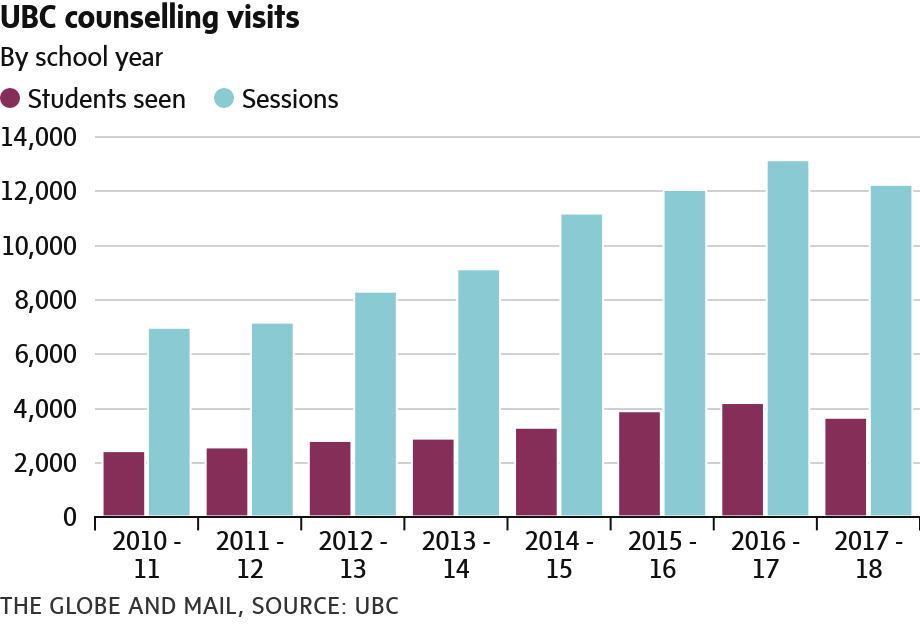

The strategy is getting the university its intended results: Data out of UBC showed a drastic shift last year, bucking upward trends of other large schools such as the University of Toronto and Queen’s University. The number of students in UBC counselling, as well as total appointments, dropped for the first time in at least seven years – by 542 students (or 13 per cent) and 906 sessions (or 7 per cent.) Dr. Cheryl Washburn, who directs UBC’s counselling services, says the drop is “directly tied” to the increase in options outside their centre, including more access points for services, online programs and resources in the wider community.

The numbers at counselling services tell a success story, but the experience of some students show there is a hidden cost. The increased demand on mental-health resources is not contained to just universities. The health-care sector is also feeling the squeeze, meaning public health practitioners are backed up, too. “Demand for care continues to exceed the supply of clinically active psychiatrists,” says Mathieu Dufour, co-chair of the Coalition of Ontario Psychiatrists. Some students seeking help off-campus, including from external psychiatrists, have been referred back to their university campuses for care.

For students who are able to pay out of pocket, options expand to include psychologists or psychotherapists – but with a going rate of more than $100 an hour, and sparse coverage under student health-care plans, these services are only accessible to economically advantaged students.

“I was really fortunate that I was able to afford the luxury,” Ms. Burnham reflected, pointing out that she’d also paid less than most patients, as her psychologist offered students pricing on a sliding scale. All told, offset marginally by a $300 allowance from her student health-insurance plan but mostly shouldered by supportive parents, she’s spent approximately $2,500 seeking help since her first year.

Unlike other students with continuing needs, Ms. Burnham wasn’t referred to her psychologist by UBC counsellors – she sought one out directly, in an effort to avoid long waits and repeated recitations of her history with mental illness, only to be referred to an external resource anyway.

“I don’t have the emotional energy to go through another process and re-explain everything to these people that may or may not actually help me in the end,” she said.

Counselling services in universities originated around the end of the Second World War, when veterans returning to campuses required specific educational and vocational supports. Decades later, the purpose of the centres is to address more broadly students’ mental-health needs. The increased demand for mental-health support on campuses can be attributed to a miscellany of factors, from changes in parenting styles to decreased stigma and increased awareness of students’ mental health. Some experts point out that increased technology use can be tied to changes in brain development and modified sleep patterns; some believe young people today are less adept at emotional self-regulation than past generations, feeling pressure to succeed, but lacking the proper mechanisms to cope with failure.

Cross-country data compiled by The Globe and Mail give a glimpse of the mounting pressure in university counselling offices. At the University of Toronto, a rise in appointments has vastly outpaced the rise of the overall student population. Its population went up 8 per cent from 2012 to 2017; in the same time frame, appointments rose approximately 40 per cent. Prior to last year’s drop, UBC’s counselling appointments had risen constantly for six years, up 89 per cent from 2010-11. The number of students being seen increased by 74 per cent in the same span.

Dalhousie University in Halifax moved to a new service model for health care in 2017, meaning they’re creating new metrics and a new baseline for tracking purposes. But data released by the university in 2015 showed a five-year increase in counselling demand, up by a total of 68 per cent. “And it’s not slowing down,” they wrote, noting that of the 1,248 students seen for initial consultations in 2013-14, 763 were put on a wait list averaging 20 days in length. Mental-health appointments at Queen’s University in Kingston have increased by 73 per cent in the past five years, far outpacing the school’s 13 per cent enrolment increase over the same time period. And at McMaster University, in Hamilton, the counselling service logged more than 11,000 visits last year – 40 per cent more than they documented in the 2012-13 school year.

The escalating demand has forced postsecondary institutions to consider anew what lies within their scope. “Colleges and universities are not treatment centres,” declares a joint action plan, In It Together, released by four Ontario postsecondary groups in 2017. Schools’ core mandate is higher education, and they would stand with their students, they said, but couldn’t meet the challenge of mental-health demand alone. The report claimed that acute and long-term mental-health support falls within the mandate of health-care providers and community agencies. They cited the pressure schools are under, and appealed for a distinction to be drawn between their “triage role” and the actual administering of long-term or acute care.

At McMaster, dean of students Sean Van Koughnett says they’d have lineups out the door if their counselling staff tried to handle all the cases that required continuing treatment. They were lucky, he explained – they had resources nearby, such as St. Joseph’s Healthcare. The hospital is strapped by demand itself, but he believes they’re still better-positioned to handle complex cases.

“The demand became such that it just wasn’t something that we should try to continue to manage, or could manage,” he told The Globe in an interview. They’ve tried, hiring four full-time counsellors and one part-time counsellor in the past two years with funds from both increased student fees and the previous Ontario government. A new wellness centre is set to open within the next year, because even if he had access to more funds, Mr. Van Koughnett says he just doesn’t have the space to put more staff right now. Their increased appointments were a better indicator of capacity than demand, he cautioned, as staff have been continually going “full tilt,” adding appointments only with more staff to shoulder the load. “It’s something we’re constantly wrestling with, as to how much we can do,” he said.

Anecdotal evidence from mental-health professionals suggests that students are arriving at school clinics with more intricate cases than ever before – and not all schools have found success in referring their most acute cases out to community resources. For the past two years at the University of Toronto, health and wellness centre director Janine Robb says she’s observed a trend where external resources and external psychiatry will refer patients back into the school’s care – “because they have the designation ‘University of Toronto student,’” she explained in an interview. “So, we’re getting more complex and acute students, which doesn’t really fit with our short-term model. It’s been a real task of negotiation.”

She says that nearby care systems such as Toronto’s Centre for Addiction and Mental Health will see students in emergencies, and will admit them as needed. “But there’s no long-term follow-up generally available,” she said. “This is ridiculous,” she added, noting that the age of most university students is such that, with early and effective intervention, the long-term burden of mental illnesses can be reduced.

“It’s really hard, if we need a student to have long-term care, to actually find that care for them.”

That returns the pressure to U of T, where counselling staff have taken to dividing up bigger offices to create more spaces to work in. They, like many other universities, have adopted a ‘stepped care’ approach. That dictates that treatment starts with the least intrusive, least intensive tactic. Not all their efforts related to mental health have gone smoothly: last summer, a new policy drew criticism from students and the Ontario Human Rights Commission alike. (The policy can place mentally ill students on mandatory leaves of absence, if the administration becomes aware of a risk where that student might harm to themselves or others.) “I don’t think it would have been a first priority for a university to be providing this much mental-health support,” Ms. Robb said, speaking broadly of the school’s efforts. “But we also have to support our students in the ways in which it’s needed. I think we do the best we can.”

The sheer volume of students is a challenge in Toronto. Four hours north, at Nipissing University in North Bay, assistant vice-president of students Casey Phillips sees the institution’s smaller size as an advantage. “Sometimes, [larger schools] might not have a student brought to their attention,” he said. “Or, because of the plethora of services that are available, navigating those might be sometimes more of a difficulty.”

They saw 30 per cent more students last year than their counsellors aided in 2012-13. At times, Mr. Phillips says the school is acting as a temporary aid of sorts – a bridge until a reading week or break, when students can access services in their hometowns that aren’t available in the North Bay community.

Across the board, schools are doing what they can with the resources available. At Queen’s University, arts student Raechel Huizinga told The Globe she was seen by an engineering faculty counsellor for months. “Those types of things wouldn’t surprise me,” said Rina Gupta, the school’s director of counselling. She said she believes staff are more often working longer hours than required, to squeeze students in. Their wellness service has increased total health-care appointments by 37 per cent since 2015-16, or 13,000 appointments, but wait times still aren’t going down.

Students get frustrated at times, sometimes taking to online groups or forums to vent about their experiences. “There have been a lot of students who have been very vocal about wait times or not being to access services, and that’s understandable if students are feeling stressed,” Dr. Gupta said. On a typical day, she says she often cancels prior commitments to address students showing up in crisis, who they try to accommodate right away. “I did that three times yesterday,” she said in a phone call.

Queen’s maintains a team of physicians, nurses, psychiatrists and occupational therapists in addition to counsellors. Other schools have their own combinations of health-care professionals to complement counselling, and some offer an additional ‘peer support’ option – a hub of student volunteers that can offer a listening ear. (This has its limitations, as students cannot prescribe or advise on medications, and they are not trained mental-health professionals.) Queen’s recently implemented 11 or 12 group options, from therapeutic groups to skill building. They’ve started looking at adding web-based components to the service, for use between appointments or while waiting for one. Ultimately, Dr. Gupta echoed the sentiment expressed by Ms. Robb in Toronto: “We’re trying our best,” she said.

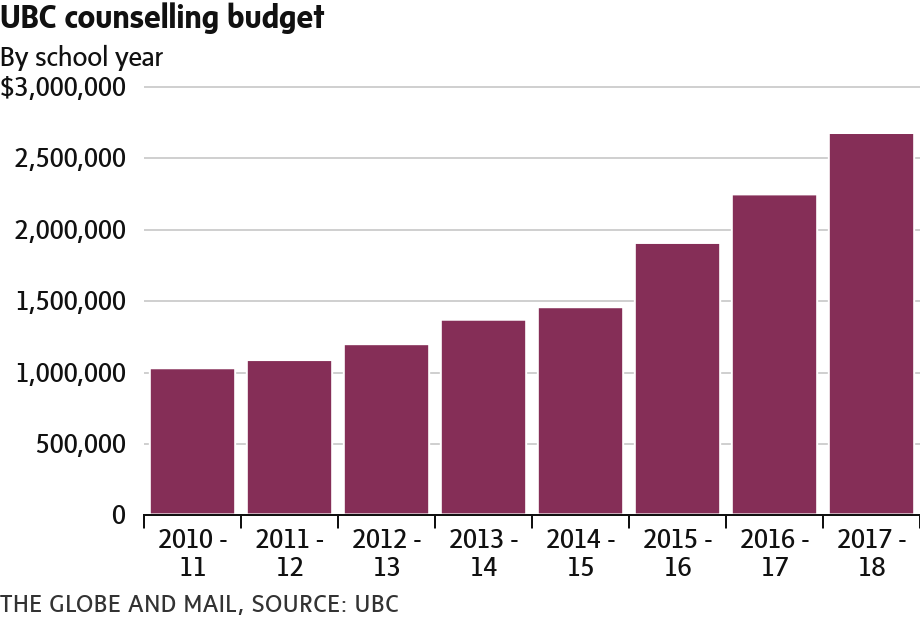

But for every school’s efforts – multimillion-dollar budgets that continue to grow, new wellness centres and redeveloped strategies – there are still students across the country feeling as if they’ve fallen through cracks. Before University of New Brunswick student Caitlin Grogan transferred to Dalhousie in 2016, she called the Halifax school on the advice of her family doctor, to make sure she could access mental-health care. Ms. Grogan has borderline personality disorder, and takes anti-depressant medication regularly. “I was mostly just looking for a counsellor to see every two weeks and just check in,” she recalls.

What followed was a series of standbys. The school didn’t book appointments in advance, Ms. Grogan said, so she waited to arrive in Halifax to set up an initial intake meeting. Advised to call for a same-day appointment, she described three days of 9 a.m. calls, during which she was repeatedly told that no slots were available. She was then prebooked for a 30-minute assessment, for which she reports waiting another two weeks. From there, she says she was left to wait for a call, which would come when there was a counsellor available to see her regularly. Months passed. Eventually, frustrated, Ms. Grogan transferred back home to New Brunswick. (Dalhousie declined to comment about Ms. Grogan’s specific experience, citing confidentiality.)

Upon her return, Ms. Grogan sought to change things at the school. She became vice-president of her student union – a position that involves advocacy on mental-health issues and assisting the assessment of campus mental-health services. The New Brunswick university is struggling a little more than usual right now, she said, with one counsellor out on maternity leave. That means more students are being referred out.

While postsecondary institutions across the country struggle with similar issues, Ms. Grogan says a viable solution will take more than new counsellors. “They’re always going to be full. We can’t hire our way out of this mental-health crisis,” she said. She urged schools to instead look into the causes of student distress.

“I’ve just become very passionate about making sure no one falls through the cracks, like I did.”

VICTORIA GIBSON

The Globe and Mail, February 14, 2019