Until a couple of years ago, Emma Thompson thought she would study theatre or music in university. She had been involved in musical theatre and decided to attend a specialized Toronto arts high school.

But in grade 11, a physics teacher sparked her interest in science. He helped her look for summer internships and choose the kind of high-school courses top engineering or science programs would require. So this fall, Ms. Thompson applied to half a dozen such university programs and is now waiting to hear which have accepted her. Already, Ryerson University has offered early admission.

“I am still taking musical theatre,” she said. “It’s a lot of work all the time, [but] … I want to keep the arts as a hobby, as something I could do as an extracurricular in university,” Ms. Thompson said.

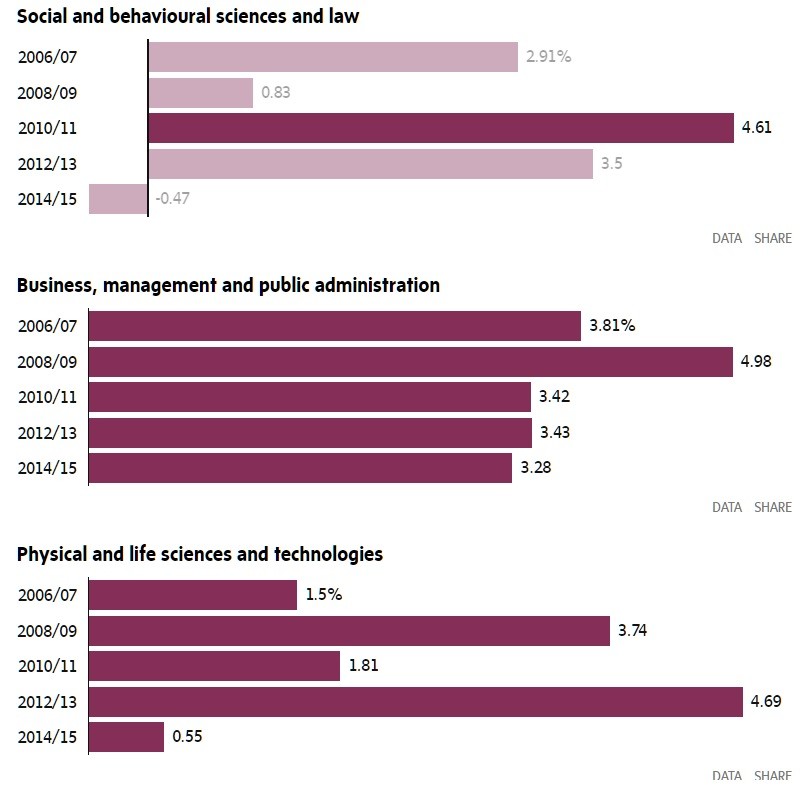

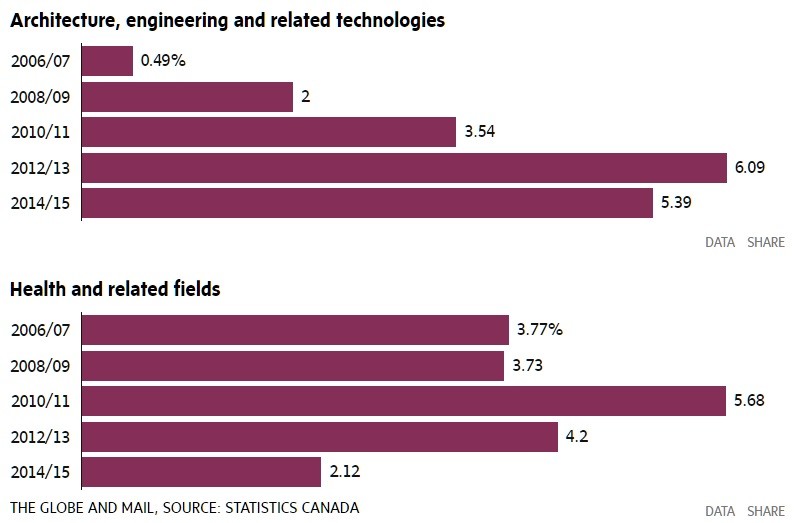

Tens of thousands of students are increasingly making the same choice, moving the arts from the centre of their lives to the side. Over the last decade, students have fled the humanities. In response, universities have cancelled individual courses, or entire specialized humanities programs. Instead of hiring tenure-track professors to replace retiring faculty, they make do with less, or turn to sessional instructors who teach when and if there is demand.

As data from Statistics Canada analyzed by The Globe and Mail reveal, there is no sign that the lack of interest in the humanities will reverse. While other fields have grown or held steady in the face of a drop in the university-aged population, enrolments in programs such as English, history or languages are down by almost 6 per cent in 2015, the last year for which national numbers are available. In response to the accelerating decline, universities are now evolving beyond temporary adjustments to permanent adaptations.

In some cases, that means combining philosophy or history with commerce. In others, it means giving humanities students the same opportunities to take on co-op work terms that have long been available to engineering or business students. Even when programs stay the same, professors are trying new approaches to teaching to keep their courses relevant.

Many of those in the humanities believe media attention and personal anecdotes about temporarily unemployed arts graduates have driven a false sense of crisis. But they also realize they must be realistic in order to survive.

“There is a certain amount of crisis of the humanities talk, that in some cases seems to have preceded rather than followed the decline in enrolments,” said Ken Cruikshank, the dean of the faculty of humanities at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ont. “We are up against that perception. Sometimes reversing it is saying ‘OK, you think you need certain kinds of skills. Maybe we can facilitate that.’”

This fall, McMaster is introducing a program that will see students take philosophy and language courses alongside business. Students in the program will graduate with a bachelor of commerce.

Those students who are not looking to hide their passion for Kant under a B.Com degree will have the option of taking a specialized commerce minor, which would put them on a fast track to an MBA.

“You could get an honours philosophy degree and an MBA in five years if you wanted,” Dr. Cruikshank said.

Other postsecondary institutions are also hoping to arrest the fall in humanities enrolments. At the University of Ottawa, students in the humanities can create interactive games and data visualizations instead of writing English essays. At Dalhousie University in Nova Scotia this fall, fourth-year social science students can spend one day a week working in a government or NGO (non-governmental organization) office. Placements include refugee legal clinics and youth development organizations.

“I think students are searching for connections between the content of their university courses and the significant real-world problems they see playing out every day,” said Frank Harvey, the dean of the faculty of arts and science at Dalhousie. “I remain convinced that a liberal arts degree can help them make a difference.”

The changes come in the wake of tough investigations into what is troubling humanities departments. At the University of Ottawa, a 2014 task force found that half of professors teaching in the humanities were part-time instructors. Last year, a task force at McMaster mused about merging some faculties. That option is off the table, but McMaster is now working to ensure that students have opportunities to take courses across all faculties, rather than be restricted to mainly arts or science.

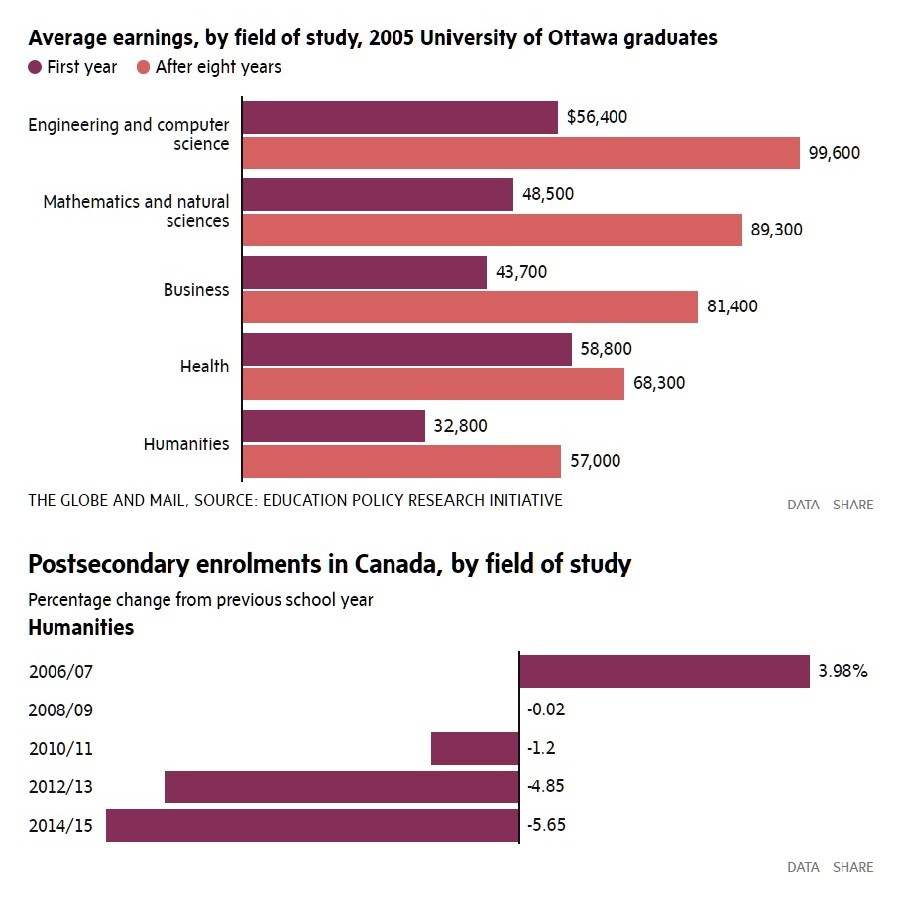

What universities also recognize, however, is that labour market outcomes are generally better outside the humanities. English, French and history majors earned approximately $20,000 to $30,000 less a year, on average, than those in engineering, math or computer science, according to Statistics Canada.

At the same time, one Canadian study on earnings among graduates from the University of Ottawa has found students in humanities and social sciences have more career stability. Over a decade, their earnings rose steadily, rather than being subjected to the boom and bust cycles experienced by their colleagues in engineering or computer science. In a follow-up study, the largest of its kind to date in Canada, the researchers looked at the earnings of graduates from 14 Canadian post-secondary institutions. They discovered that those who took humanities or social sciences did indeed make less money than engineers almost a decade after leaving the classroom. But their earnings rose at similar rates.

The message is that following your passion leaves plenty of room for career advancement, the researchers say.

“The next thing is to figure out what exactly it is that allows humanities grads to do as well as they do in the labour market,” said Ross Finnie, the director of the Education Policy Researcher Initiative at the University of Ottawa, where the 14-institution study was released last summer. “We really don’t know very well what [their] skills are, the value of those skills in the labour market, or the potential role of higher education in helping students develop those skills,” he said in an e-mail interview.

One way to help students compete once they graduate is to more consciously show them what they are learning when they’re writing an English or philosophy essay, Dr. Cruikshank said.

At McMaster, for example, first-year courses include a skills component.

“We want our students to graduate with a clearer sense of the skills they have acquired,” he said. “Alumni recognize that they gained project management skills, but a student in progress does not always realize what they are acquiring.”

SIMONA CHIOSE – EDUCATION REPORTER

The Globe and Mail

Published Friday, Mar. 03, 2017 7:49PM EST

Last updated Sunday, Mar. 05, 2017 1:15PM EST