A new report by the Ontario Human Rights Commission shows that Black people are more likely than other racialized groups or white people to be arrested, charged or subjected to use of force by Toronto police.

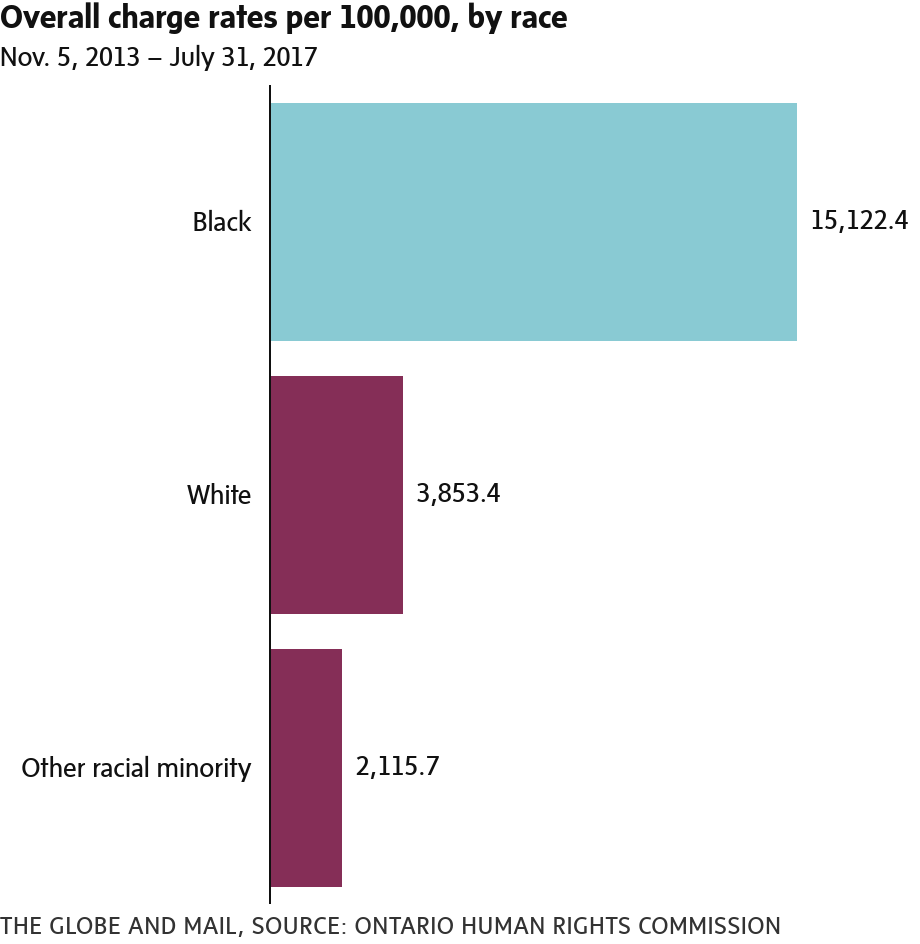

A Disparate Impact, the second report released by the OHRC as part of a public inquiry launched in 2017 to address anti-Black racism, discrimination and profiling by the Toronto Police Service, has found that while Black people make up less than 10 per cent of Toronto’s population, they represented almost a third of all charges analyzed by researchers.

While commission members acknowledged that the information will likely come as no surprise to the city’s Black communities or their allies, they hope the “highly disturbing” findings will put pressure on decision makers at a time of global reckoning around policing.

“The time for debate about whether systemic racism or anti-Black racial bias exists within the Toronto Police Service is over,” OHRC Interim Chief Commissioner Ena Chadha said in a statement Monday. “It is time for action that results in concrete changes to the institutions and systems of law enforcement that are accountable for the racial disparities found in these two reports.”

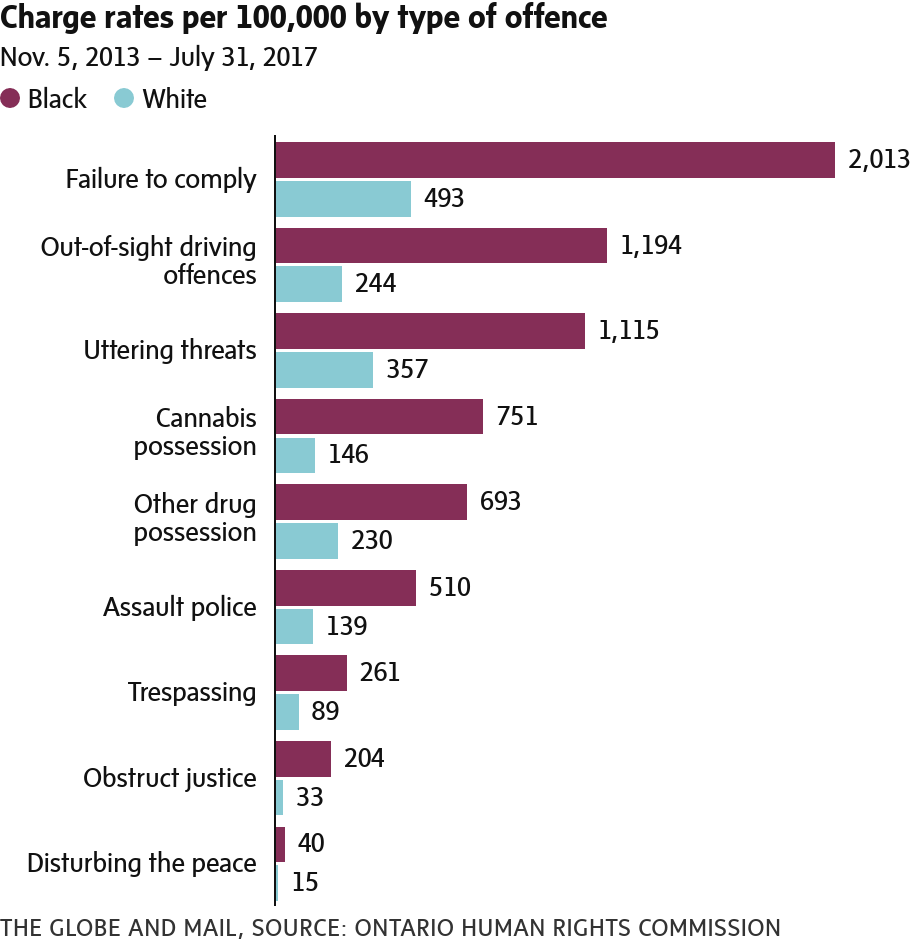

Researchers, led by University of Toronto criminologist Scot Wortley, analyzed Toronto Police data from 2013 to 2017 for nine offences they believed would be likely to involve the exercise of police discretion, such as driving offences, failure to comply with a condition or disturbing the peace.

They found that the charge rate for Black people was 3.9 times higher than for white people, and 7.1 times higher than the rate for other racialized groups.

The report also debunked some of the common stereotypes used to dismiss why Black people are overrepresented in these statistics, such as that they live in high-crime areas; it determined that the overrepresentation was present in both high- and low-crime patrol zones.

The research builds on a previous OHRC report released in December, 2018, which looked at data collected by the Special Investigations Unit, a civilian oversight agency that probes all cases in Ontario in which people were allegedly seriously injured, sexually assaulted or killed by police. That report found that Black people were disproportionately overrepresented in all areas, especially fatal shootings.

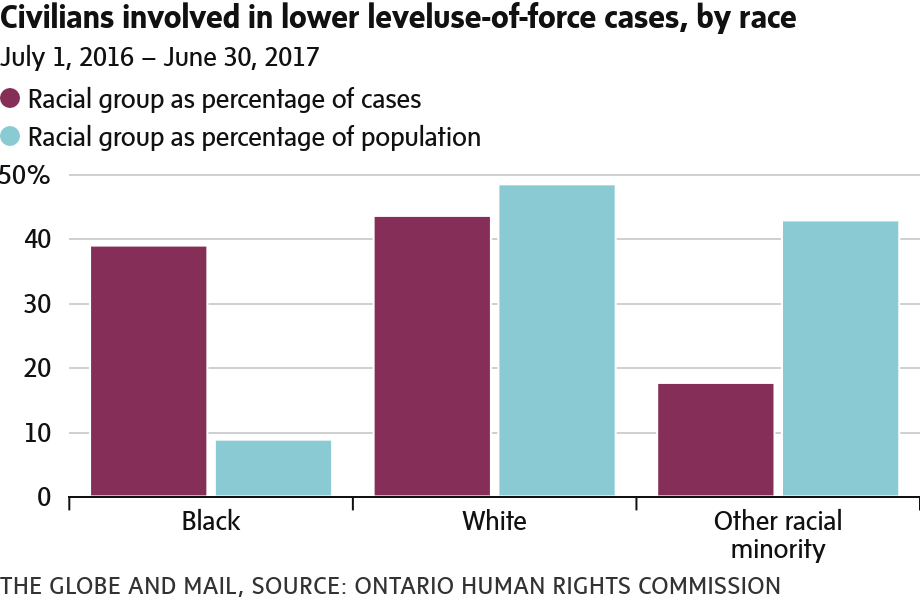

For this report, researchers also analyzed use-of-force data in lower level cases not serious enough to meet the threshold of being investigated by the SIU and found that Black people were once again “grossly over-represented” – present in 38.9 per cent of cases, despite the fact that they constitute 8.8 per cent of Toronto’s population.

“The current attention on policing Black lives has primarily focused on police shootings,” the report says. “[This report] … adds an important dimension to the current conversation and reflects the everyday racism Black communities face. These reports and the findings they contain add considerable weight to the groundswell of calls for systemic reform to policing services.”

The Commission said it expects to release its final report in the inquiry soon. In the meantime, the Commission has called on the Toronto Police Service, its board and the City of Toronto to “adopt legally binding remedies that will result in fundamental shifts in the practices and culture of policing, and address and eliminate systemic racism and anti-Black racial bias in policing.”

The Commission has also called on the province “to establish a legislative and regulatory framework to directly address systemic racism and anti-Black racial bias in policing.” It also stressed that provincial law must “provide transparent and effective accountability processes to ensure that officers who engage in racial profiling or discrimination are effectively disciplined.”

Solicitor-General Sylvia Jones said Monday that the province has been compelling Ontario police forces to submit race-based data in use-of-force cases since January.

The SIU said Monday that it will begin collecting race-based data in its investigations, on a voluntary basis, beginning in October.

In a joint statement Monday, the Toronto Police Service and its board called the report “vitally important to our continued efforts to critically examine and act to address anti-Black racism. … The conclusions of this report come at a pivotal time in history, as people around the world are engaged in a critical dialogue about anti-Black racism, policing, accountability and reform.”

Racial justice lawyer Anthony Morgan, manager of the City of Toronto’s Confronting Anti-Black Racism Unit, said that the report’s findings should not come as a surprise to Toronto’s Black communities and their allies – and that they cannot be faulted for responding to this latest report by saying that “we don’t need another report.”

But he stressed that the report is for police officers, politicians and other decision makers within the justice system, who he hopes will finally pay attention.

“It’s what translates after,” he said. “As I’ve said [before], we don’t have an information problem, we have an accountability problem when it comes to policing in this city. And so at the end of the day, public-policy makers, decision makers, politicians and especially actors within the policing and justice system being held accountable … is what will ultimately determine how valuable or useful these reports are.”

MOLLY HAYES

CRIME AND JUSTICE

The Globe and Mail, August 10, 2020