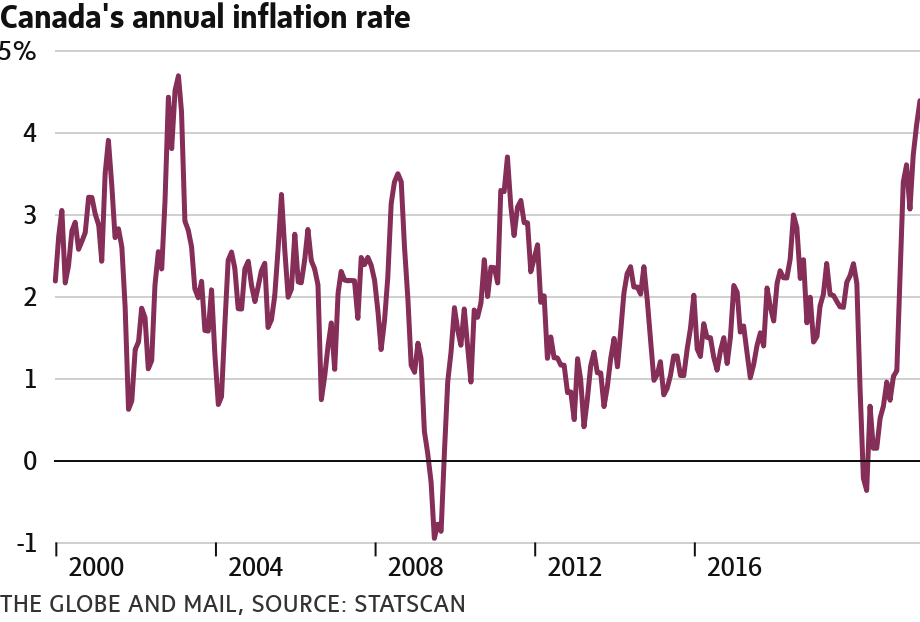

Canadian inflation surged in September at the fastest pace since 2003 due to higher gas and housing costs, adding fuel to a boisterous debate over how long prices will rise rapidly.

The consumer price index (CPI) rose 4.4 per cent in September from a year earlier, Statistics Canada said on Wednesday, up from 4.1 per cent in August. It was the sixth consecutive month that inflation has exceeded the Bank of Canada’s target range of 1 per cent to 3 per cent.

The acceleration was heavily influenced by gasoline prices, which jumped 33 per cent from a year ago. Excluding gas, the CPI rose 3.5 per cent. Prices were higher in all eight major components, including hefty gains in shelter (4.8 per cent) and food (3.9 per cent).

“It’s your home, it’s your car, it’s your groceries, it’s your utilities” that are driving up inflation, Derek Holt, head of capital markets economics at Bank of Nova Scotia, said in an interview. “It’s speaking to a rather large chunk of the typical household’s budget.”

The Bank of Canada has long maintained that steeper inflation is a temporary phenomenon owing to such factors as supply-chain disruptions and comparisons with tepid prices a year ago. It expects annual inflation to weaken as pandemic-related factors subside.

However, BoC governor Tiff Macklem recently acknowledged that high inflation could be “a little more persistent” than previously thought, in part because the problems in supply chains that are preventing goods from getting to consumers are not fading away.

As lofty inflation drags on, a schism is emerging between the central bank and Bay Street.

Royal Bank of Canada chief executive officer Dave McKay said last week that persistent inflation is building and that some CEOs disagree with central bankers’ view that the recent inflation spike is temporary. A day later, National Bank of Canada CEO Louis Vachon echoed those concerns.

Furthermore, trading in contracts tied to future interest rates suggests the Bank of Canada will hike its key lending rate three times next year, taking it to 1 per cent from the current 0.25 per cent. Traders are indicating the increases will start in April, a more aggressive timeline than the Bank of Canada has signalled thus far.

Wednesday’s report offered fresh evidence of supply troubles. For one, prices for passenger vehicles rose 7.2 per cent from a year ago. The auto industry is grappling with a global shortage of computer chips, resulting in weaker production and lower inventories at car dealerships.

While the CPI doesn’t entirely capture the frenzy in Canada’s housing market, there are pockets with substantial price increases. Notably, the homeowners’ replacement cost index – which is tied to the price of new home structures – jumped 14.4 per cent in September from a year earlier.

The Bank of Canada’s core measures of inflation – which strip out components that have rapid price fluctuations – rose by an average of 2.7 per cent, a slight uptick from 2.6 per cent in August. As well, Statscan noted there have been month-to-month CPI increases for nine consecutive months.

From July through September, annual inflation averaged 4.1 per cent, or two-10ths of a percentage point higher than what the Bank of Canada projected in July, its most recent forecast. The bank has called for inflation of 3.5 per cent in the final quarter of 2021 – a projection that looks increasingly unlikely given record prices at gas pumps this month and continuing stress in global supply chains.

That call is looking “light,” Bank of Montreal chief economist Doug Porter said in a note to clients, with the CPI likely to remain above 4 per cent in the coming months. (Some analysts think inflation could hit 5 per cent.) BMO expects inflation to average 3.3 per cent this year and next.

“Suffice it to say, that strains the definition of transitory,” Mr. Porter said.

The Bank of Canada will issue a new forecast at next week’s rate decision, and analysts expect it to hold its key lending rate at 0.25 per cent, where it’s been since the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic as part of its crisis response to support the economy. The bank has said it won’t raise interest rates until the country’s economic output is back to potential. In its most recent forecast, the bank didn’t see this happening until the second half of 2022.

Still, many analysts think the BoC will be forced to act sooner. Scotiabank is now projecting the central bank will hike its rate four times in the second half of 2022, and another four times the next year, taking the key rate to 2.25 per cent. (That would be the highest since 2008.)

Inflation “doesn’t have to be alarmingly hot in order to merit moving away from crisis levels of stimulus in the system,” Mr. Holt said, pointing to positive developments in the economy, such as a rebound in employment and high rates of vaccination.

Inflation expectations are mounting among businesses and consumers.

Nearly half of companies expect inflation will top 3 per cent over the next two years, according to Bank of Canada survey results published on Monday. While businesses are broadly upbeat about their prospects, they’re also struggling to find enough workers and facing supply disruptions, and many plan to pass higher costs to customers.

A separate BoC survey published on Monday found that Canadians expect inflation to stay high a while longer. The median prediction for inflation a year from now was 3.72 per cent, the highest since the survey began in 2014. Respondents saw inflation at about 3 per cent two years and five years from now.

“Most consumers reported that their cost of living has gone up since the start of the pandemic,” the BoC said.

MATT LUNDY

ECONOMICS REPORTER

The Globe and Mail, October 20, 2021