Days ahead of the federal government’s release of its multiyear immigration targets, the latest results in an annual poll suggest Canadians support current immigration levels more than they have in nearly half a century.

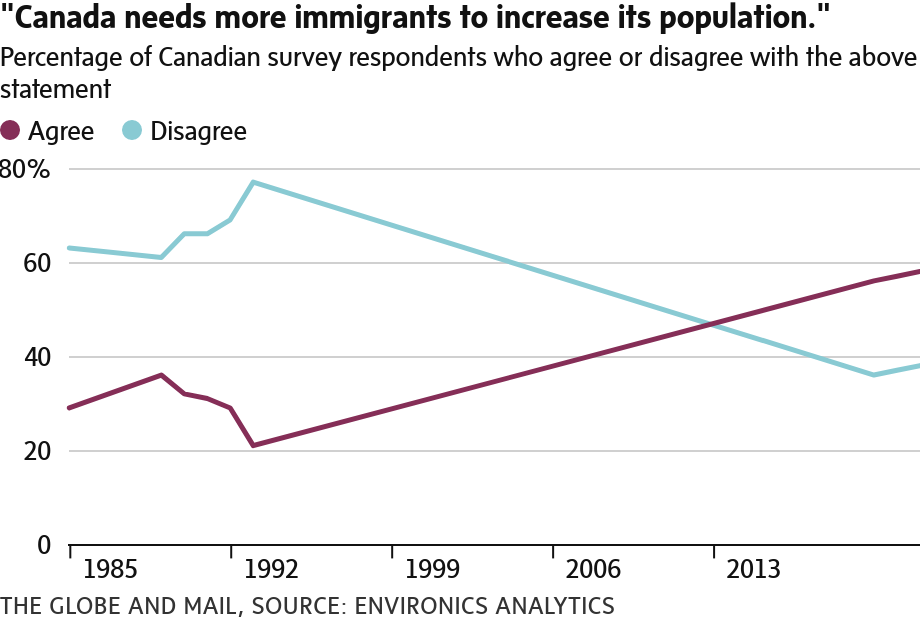

The poll, conducted by the Environics Institute for Survey Research, found 69 per cent of those surveyed were in support of current levels of immigration, compared with just 35 per cent in 1977.

Since the Justin Trudeau government came to power in 2015, annual immigration numbers have soared from less than 300,000 a year to a target of almost 450,000 in 2023. This week, Ottawa will announce immigration targets for the years ahead, including a breakdown of numbers between different immigration streams: economic, family sponsorship and humanitarian, which includes refugees.

But even with broad public support, the country’s ambitious immigration targets only tell half the story. Immigrants still face many difficulties once they arrive in Canada, including a housing crisis, rising food costs owing to inflation and an underfunded settlement sector to help them find work and access services such as health care and education.

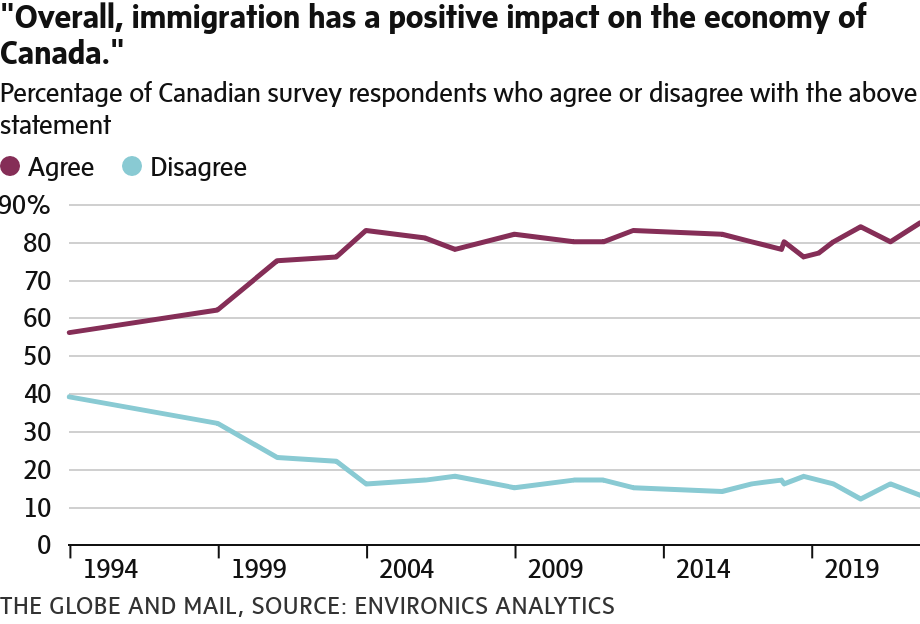

“We’ve pretty much reached a consensus,” said Keith Neuman, a senior associate at the Environics Institute: Not only is immigration good for the economy, it is a vital part of it. “The outstanding issues are about integration,” he said.

An overwhelming majority of those surveyed – 85 per cent – agreed that immigration has a positive impact on the country’s economy, a statement that proved controversial just three decades ago (when only 56 per cent said they agreed).

Environics partnered on this poll with the Century Initiative, a charitable organization that has campaigned for strong immigration levels in Canada. The poll was conducted by phone with 2,000 Canadians between Sept. 6 and Sept. 30. A sample of this size drawn from the population produces results accurate to within plus or minus 2.2 percentage points in 19 out of 20 samples.

When asked whether they agree or disagree with the statement “There are too many immigrants coming into this country who are not adopting Canadian values,” 46 per cent agreed, compared to 72 per cent in 1993.

(In the case of this question and others in the poll with a negative bias, pollsters sometimes phrase statements in a provocative way because that can generate stronger responses, Mr. Neuman said. They also want to preserve the wording of the statements over the decades so they can more accurately track how attitudes may have shifted over time.)

But an external evaluation of how successfully an immigrant has integrated – which may be largely based on how fluently they speak one of Canada’s official languages – might lack a nuanced understanding of the myriad challenges immigrants face after they arrive, said Neda Maghbouleh, Canada Research Chair in Migration, Race and Identity, who runs a refugee research project at the University of Toronto-Mississauga.

Prof. Maghbouleh said the greatest challenge to successful integration among the population she’s studied is housing and how there simply isn’t enough to accommodate all who are arriving in Canada, no matter what stream they’re coming in on.

“Without proper integration, any economic gains are flimsy or short-lived,” she said.

“For the families that are in our study, their urgent situations are pretty much always about housing, about getting evicted. It’s about a family member or someone in their network losing their housing and then having to join into an already overcrowded environment,” she said.

The settlement sector – meant to help immigrants with housing, but also with everything from language training to résumé writing to registering their children for school – has also faced significant strains.

A 2021 report from the Association for Canadian Studies that surveyed workers at settlement agencies found that the field is in turmoil. While record numbers of immigrants are arriving in Canada, the programs designed to help them adjust to their new homes and thrive are not consistently funded, and there is high turnover of workers because their wages aren’t competitive.

In Nova Scotia, the rate of retention for immigrants has been increasing, and currently sits at 71 per cent, meaning those who arrive in the province are finding work and settling into the region, rather than decamping for other parts of the country, as has long been the trend. But having that many more immigrants stay in Nova Scotia means front-line staff are feeling the strain.

Jennifer Watts, chief executive officer of Immigrant Services Association of Nova Scotia, says the biggest challenge her organization faces is development and support for staff.

Another issue Ms. Watts and the ACS report noted is that as the federal government’s targets for different streams of immigrants shifts, so does the funding for different programs, which can make long-term planning difficult.

From 2018 to 2021, the number of permanent residents arriving in Nova Scotia increased 51 per cent, but the funding from the federal government to ISANS in that same period only increased 7 per cent.

“When the country as a whole is committing to higher immigration levels, leaders at that level who are making that decision need to say, ‘This is going to take a significant amount of money to help people settle and move quickly into the labour market and succeed,’ ” Ms. Watts said.

DAKSHANA BASCARAMURTY

The Globe and Mail, October 25, 2022