Lorelai and Rory Gilmore drink a lot of coffee on the television series Gilmore Girls. So it was important for Else Watt to prominently display a coffee mug in the pandemic diorama she made for a Grade 12 English class assignment.

Throughout all the bad news of the past 15 months, the show became a bright spot: She’d spend evenings watching episodes with her mom, growing closer as they caught up on the adventures of the onscreen mother-daughter pair.

The mug with a message tucked inside explained the new bond and sat on top of Ms. Watt’s project – a bookshelf crafted out of cardboard. Another note reflected on the Black Lives Matter movement rested between the pages of the book How to Be an Antiracist. A pair of red children’s shoes held a note about unmarked graves at residential school sites.

“I cried writing some of the assignments. It was very emotional. … This has been such a weird year,” said Ms. Watt, who graduated last month from Fort Richmond Collegiate in Winnipeg. “It was very nice to have a project where we could put our heart and soul into it and then be able to see that result.”

In classrooms across the country, teachers found creative ways to address this historic moment. From time capsules and dioramas, to music and journals, teachers and students found themselves grappling with a global crisis in real time together. For many students, the classroom projects and conversations gave them what they urgently needed: perspective, room to talk and ways to cope. For teachers, it was an opportunity to witness their kids processing a widescale emergency – and to bond with them through it.

Ms. Watt’s English teacher, Stephen Holbrow, asked the class to be “recorders of our times” and create memory capsules. One classmate shared a photograph of her large family gathering in India, prepandemic. In another family portrait, taken on the same date a year later, there were only four of them at their home in Winnipeg. Another student uploaded two songs that he wrote, one of his experiences during the pandemic, the other a social commentary on world events.

Mr. Holbrow recalled that before the crisis, kids were not always excited to hold on to their work. “When I would ask ‘How many people want their essays back?’ Crickets. But something like this, they’re interested.”

Poring over his students’ assignments, the teacher grew emotional, stunned at how original and genuine their accounts had become.

“We all have stories that only we can tell. … Their words and their thoughts and their reflections and recollections, they’re so authentic,” he said. “They’ve struggled. They’ve overcome. They continue to overcome.”

Teachers across the country urged their students to narrate this time, to record their feelings and “mark this as a historical moment, rather than just living in it,” according to Samantha Cutrara, a Toronto history education strategist who interviewed dozens of educators and scholars in the first wave for an online video series.

Ms. Cutrara is examining whether this crisis will change history teaching: Will these lessons move beyond the memorization of dates and names, to exploring people’s emotions during historical events? “Those questions provide greater meaning and connection for students,” she said.

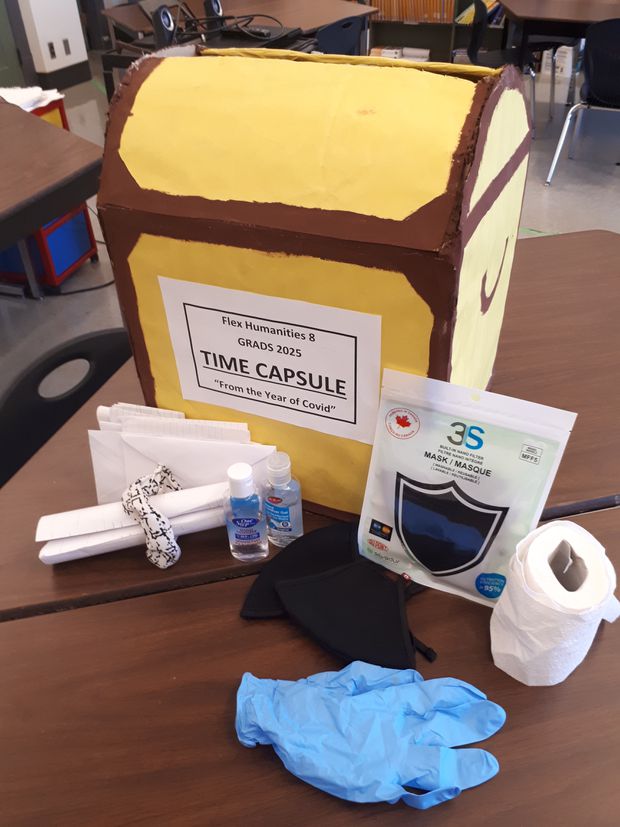

In Vancouver, Chris Moon’s Grade 8 students gave serious thought to what they would put inside their pandemic time capsule, a yellow paper chest labelled “From the Year of Covid.” The kids gathered recognizable artifacts – masks, gloves, hand sanitizer and toilet paper rolls – but also newspaper clippings, journal entries filled with reflections made in real time and letters to their future selves. The students are not to unseal their chest until Grade 12.

“Living through this pandemic has focused their attention and inspired them to work on this stuff,” said Mr. Moon, who teaches history, economics and social studies at Vancouver Technical Secondary School.

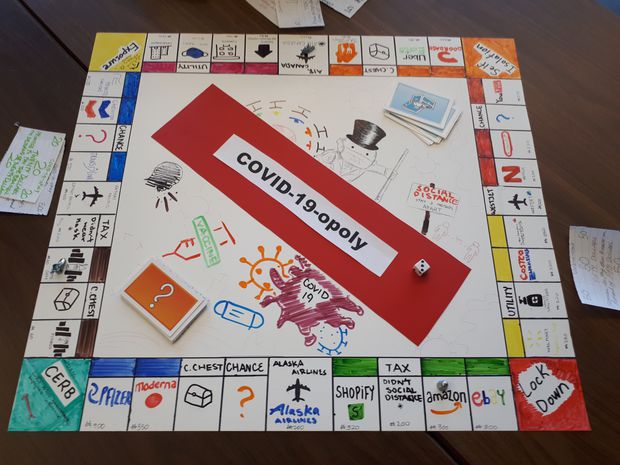

Vancouver Technical Secondary teacher Chris Moon asked Grade 12 students in his economic theory course to redesign the game of Monopoly for the pandemic era. Left to right are students Simon Chen, Riya Wang and Jody Liu who modeled their board to reflect the realities of the past 16 months, from vaccines and masks to Netflix binges and takeout from UberEats. VANCOUVER TECHNICAL SECONDARY

For his Grade 12 economic theory class, Mr. Moon challenged students to redesign Monopoly for the pandemic era. Students Simon Chen, Riya Wang and Jody Liu filled their board, dubbed “COVID-19-opoly,” with timely references: vaccines, lockdowns and self-isolation; Netflix binges and takeout from DoorDash; CERB unemployment benefits and businesses beleaguered by COVID-19. The students created their game in an impressive 60 minutes.

“It was good to talk through these issues related to COVID in the classroom setting, or to my parents, teachers or counsellor,” said Mr. Chen, 17. “Everyone is there for you.”

Ms. Cutrara heard from teachers that some students struggled with the emotion check-ins at school – requests to “spill their pain all the time, to always talk about COVID,” as she put it. In those cases, instructors told her they took a lighter approach. One high-school teacher she interviewed asked her pupils, “What are your go-to snacks right now? What are you listening to? What are you binging?”

Others suggested more private methods of reflection.

Mr. Chen found it helpful to use a school journal to document “once-in-a-lifetime” pandemic scenes. In the early bewildering days of March, 2020, he travelled on an empty bus to a currency exchange downtown, only to find the city deserted. “Vancouver was dead: I didn’t see a single human being walking downtown at 10 a.m. Shops were starting to board up their front displays with wood to keep thieves away,” said Mr. Chen, who had no luck exchanging his American dollars because the exchange ran out of cash. “It felt terrifying.”

Journaling helped him deal with such unnerving moments. “It would keep me calm when … you’re huddled in your room, thinking, when will times be normal?”

Such pandemic-related assignments gave students tools to memorialize and process what was unfolding around them, according to Dale Martelli, who teaches history, philosophy and classics at the same Vancouver high school.

“You’re giving them intellectual scaffolding into their present experience,” Mr. Martelli said. “This pandemic is not an isolated event, but what society does with history is it assumes that what we’re going through right now is so unique, that nobody’s had to face it in the past. … These lessons give students perspective and distance.”

The past months have been marked by surreal moments in his classroom. “Kids are wearing their masks and then we put up on the screen photographs of people wearing their masks in 1918,” Mr. Martelli recalled of a Grade 12 lesson on the 1918 flu. “It was interesting to watch. They could see what that was like.”

Teacher Chris Moon’s Grade 8 students created a pandemic time capsule they’ll unseal in 2025, when they graduate from Grade 12 at Vancouver Technical Secondary School. What’s going inside? Masks, gloves, sanitizer, letters to their future selves – and toilet paper. VANCOUVER TECHNICAL SECONDARY SCHOOL

His colleague Mr. Moon noticed student interest piquing during discussions about the Black Death in his Grade 8 and 9 history classes: “This made it real for them – it wasn’t a boring history lesson. They were able to make the empathetic connection to what people lived through.”

High-school teacher Barry Halloran witnessed the same attentiveness during his lessons about the 1918 flu, the SARS outbreak of 2003, the 1300s bubonic plague and the religious and economic upheavals that followed. Mr. Halloran, who teaches history, geography and theory of knowledge at Sydney Academy in Cape Breton, said students were also keen to discuss a post-COVID-19 future, from mask wearing to an emerging work-from-home culture.

With his encouragement, some students kept daily diaries throughout the pandemic. “I said, ‘You can look back at that 20, 30 years later and show it to your grandchildren. Those are your thoughts and feelings of how you went through this.’”

As case counts spiked and lockdowns persisted, he grew impressed with his students’ maturity, realism and understanding of the crisis: “We don’t give them enough credit sometimes.”

Toronto teacher Amanda Merpaw echoed that sentiment. During the shutdown of spring 2020, she and her colleagues at Bishop Strachan School tasked the Grade 7 students with creating a pandemic time capsule or a curated exhibit. The project continued this past academic year with a new cohort.

Students submitted photographs of their workspaces during remote learning, as well as selfies in masks. One snapped photos of “sold out” signs for toilet paper and hand sanitizer; others took pictures of cooking with family, or games night. Some documented social movements such as Black Lives Matter.

When studying historically significant moments in time, students often don’t see themselves in what they’re learning, Ms. Merpaw said. The idea of preserving material from their own lives was more engaging, she found.

“It’s a curious, thoughtful age,” she said. “This is an opportunity for us to actively be agents in preserving the stories that we feel should be preserved about our own lives.”

One of Ms. Merpaw’s students, 12-year-old Kira Jamal, photographed a page in her day planner; it captured the times of her online ballet and yoga lessons. She added a picture of the COVID-19 screener students had to fill out before walking into the school building.

Kira said there’s a feeling of sadness when she thinks about how much of her life was online. There is also pride, she added, in knowing how she and her peers overcame so much disruption.

“History is something you look back on, but I think this assignment was to … understand how we’re living through history.”

CAROLINE ALPHONSO, EDUCATION REPORTER

ZOSIA BIELSKI

The Globe and Mail, July 10, 2021