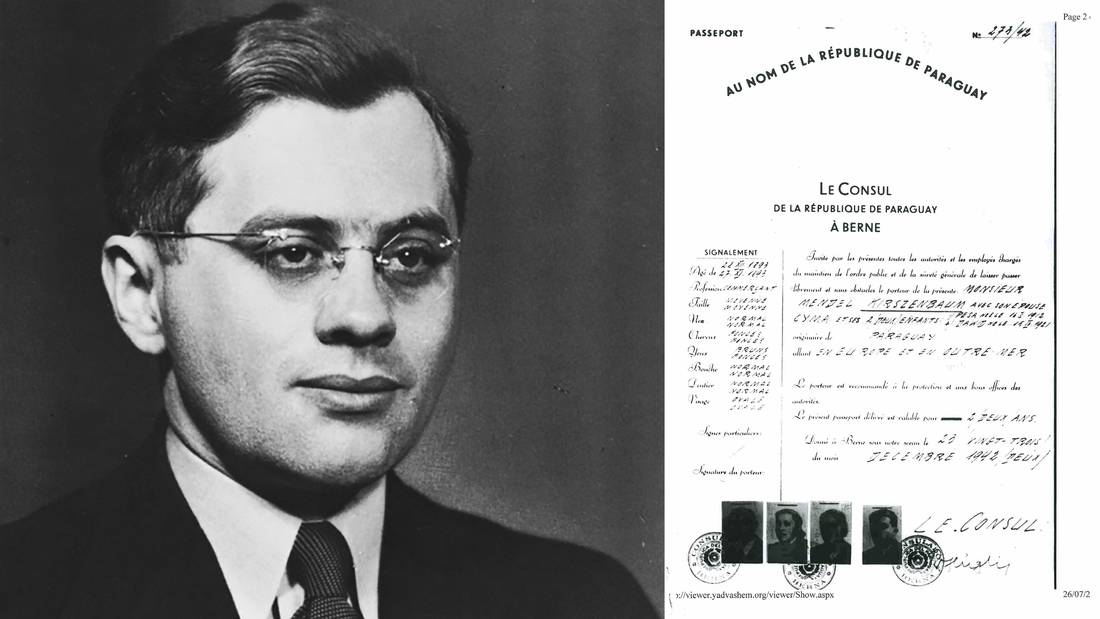

Documents stored in Switzerland, Jerusalem and Washington – shared exclusively with The Globe and Mail and Dziennik Gazeta Prawna, a Polish newspaper – reveal Julius Kuhl’s role as a saviour of hundreds, perhaps thousands of fellow Jews during the Holocaust. UNITED STATES HOLOCAUST MEMORIAL MUSEUM, COURTESY OF ERIC SAUL, LEFT, AND DZIENNIK GAZETA PRAWNA

He lived for decades in relative anonymity in Toronto, where he ran a construction company. But documents shared with The Globe show that Julius Kuhl – who died in 1985 – should have been one of Canada’s most celebrated citizens, a hero of the Holocaust who saved hundreds, perhaps thousands, of lives, Mark MacKinnon reports.

Julius Kuhl arrived in Toronto shortly after the Second World War with his young family and a suitcase full of Swiss watches that he hoped to sell.

He was also carrying a story of bravery and sorrow that he shared only with those close to him – one that might have made him an international celebrity had he chosen to tell it.

Mr. Kuhl’s death in 1985 made no headlines in Canada or beyond. But documents stored in Switzerland, Jerusalem and Washington – shared exclusively with The Globe and Mail and Dziennik Gazeta Prawna, a Polish newspaper – reveal Mr. Kuhl’s role as a saviour of hundreds, perhaps thousands of fellow Jews during the Holocaust. It is a story that deserves to be considered alongside those of famous Holocaust heroes such as Oskar Schindler and Raoul Wallenberg.

Described by his family as a short, devout and gregarious man who was constantly puffing on a cigar, Mr. Kuhl was a low-level diplomat at the Polish legation in Bern, the Swiss capital, during the Second World War. He was also the centre of a network that manufactured fake Latin American passports that were then smuggled into Nazi-occupied Europe.

Personal letters, diplomatic cables and Swiss police records show that, starting in 1941, Mr. Kuhl acquired thousands of blank passports from the consuls of Paraguay and other South and Central American countries in Switzerland. He and a colleague then entered by hand the names and dates of birth of European Jews – including many who were trapped inside the Warsaw Ghetto – before pasting in their black-and-white photos.

The effort continued for two years – until Swiss police, anxious to avoid irritating Hitler’s Germany, broke up the fake documents ring. They brought Mr. Kuhl and his collaborators in for questioning and demanded that the Polish legation, which represented the London-based government-in-exile of Nazi-occupied Poland, dismiss Mr. Kuhl.

“He should be as well known as Schindler, because he saved as many lives as Schindler,” said Markus Blechner, who worked for years to collect the documents proving the tale he heard as a child about Mr. Kuhl and the life-saving passports. Mr. Blechner, the grandson of Holocaust victims, took up the cause of preserving Mr. Kuhl’s story after Mr. Kuhl attended his bar mitzvah as an honoured guest shortly after the war.

Mr. Schindler protected more than 1,000 Jews by employing them at his factory in Nazi-occupied Poland. Mr. Wallenberg saved almost 10,000 Hungarian Jews by issuing them protective passports identifying them as Swedish citizens.

One of the reasons Mr. Kuhl’s story isn’t as widely known is that his passport scheme was only partly successful. Mr. Blechner, who now serves as the honorary Polish consul in Zurich, says thousands of fake passports were distributed via Mr. Kuhl’s network, but only a minority of the recipients are believed to have survived the Holocaust.

Jews holding passports from neutral countries were considered exempt from Nazi laws that confined Jews to ghettos and mandated that they identify themselves by wearing yellow stars on their clothing. Those third-country passports allowed many Jews to flee ahead of the mass exterminations that followed.

An estimated six million European Jews were murdered during the Holocaust.

While some of the Jews who received passports produced in Switzerland used them to escape from Nazi-occupied Europe, the majority were sent to internment camps – many, apparently, to a camp in Vittel, in Vichy France. Mr. Blechner says the Nazis’ original plan was to hold the “Latin Americans” until they could be traded for German citizens detained in camps in Canada and the United States.

But the sheer number of Latin American passport holders in occupied Poland eventually raised suspicions. As Swiss police moved to shut down Mr. Kuhl’s passport ring in the fall of 1943, Germany demanded that Latin American countries verify that the passport holders were really their citizens.

When Latin American governments said they had no knowledge of the passport holders, the Jews in Vittel and other internment camps were sent to Auschwitz and the horrific fate from which Mr. Kuhl’s network had tried to save them.

Another reason Mr. Kuhl’s exploits went unheralded is that Mr. Kuhl himself was uninterested in publicizing or romanticizing his exploits.

“[He] wasn’t interested in fame. He did this for a certain period in time, then he was selling watches in Toronto, then he became a construction magnate. People say, ‘Why didn’t he promote his story?’ Because he was busy,” said Mr. Kuhl’s son-in-law, Israel Singer. “He was a man trying to build a new life, just like the [Holocaust] survivors were.”

But Mr. Kuhl did tell his four children – two of whom still live in Toronto – and many grandchildren about the work he did during the war. The inspiring story they heard is supported by documents seen by The Globe and Mail in Bern, as well as by photocopied passports and other records that were anonymously donated to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum shortly after Mr. Kuhl’s death. Other documents that corroborate Mr. Kuhl’s heroics are stored in the archives of the Yad Vashem museum in Jerusalem.

A 1945 letter from the Israel World Organization states that Mr. Kuhl and his colleagues played a critical role in “rescuing many hundreds of Polish Jews.”

“These stories are not apocryphal. They’re actually real. There’s documentation,” said Mr. Singer, who served from 1986 to 2001 as secretary-general of the World Jewish Congress and then as chairman until 2006 – doing work, he said, that was frequently inspired by the legacy and teachings of his father-in-law.

One of the many saved by Mr. Kuhl’s efforts was Aharon Rokeach, the chief rabbi of the Belz Hasidic dynasty. Mr. Rokeach was considered a top target of the Gestapo, and saving the rabbi became paramount for the Hasidim.

He escaped Nazi-occupied Europe in 1943 using a passport created by Mr. Kuhl and sent via diplomatic pouch by Archbishop Filippo Bernardini, the papal nuncio to Bern who repeatedly used his office to aid Mr. Kuhl’s efforts. The rescue preserved the lineage of the Belzer dynasty, which has since re-established itself in Israel.

Mr. Kuhl’s tombstone near Bnei Brak in Israel says he saved the lives of thousands of Jews, including that of Mr. Rokeach. Mr. Singer says the inscription was added at the “insistence” of the rabbi’s son.

Mr. Kuhl was born into poverty in the southeastern Polish town of Sanok in 1917 but was sent at the age of nine to live with his uncle in Zurich. His father had died when he was young, and his mother wanted him to get a better education than he could receive in Sanok. Mr. Kuhl fulfilled that wish by obtaining a PhD in economics shortly before the outbreak of the war.

His mother was deported to Siberia after the Nazi-Soviet invasion of Poland on Sept. 1, 1939. She died shortly after the end of the war.

In 1940, Mr. Kuhl was hired by the Polish legation as deputy head of the consular section, with a special remit to aid Polish refugees.

The passport-smuggling operation began in October, 1941. The first rescue was accomplished by Eli Sturnbuch, a Polish Jew living in Switzerland who purchased a blank Paraguayan passport in Bern and filled it in with the details of his fiancée, Guta Eisenzweig, who was trapped in the Warsaw Ghetto.

When that effort succeeded, Switzerland’s Jewish community realized they might be able to save far more people. Mr. Kuhl and his network began buying dozens, then hundreds, of blank Paraguayan passports from the co-operative Paraguayan consul in Bern.

As the operation expanded, the network began buying blank passports from other countries that had remained neutral. Bank transfers found among the documents in Bern show that American Jews aided the effort by sending money via the Polish consulate in New York.

Mr. Kuhl and his colleague Konstanty Rokicky filled in each document by hand from the safety provided by the Polish legation’s diplomatic status.

Another key figure in the operation was Adolf Silberschein, a Polish Jew who fortuitously happened to be in Switzerland attending a conference when the war began. In exile, Mr. Silberschein established a group called the Committee for Relief of the War-Stricken Jewish Population and sent regular lists to Mr. Kuhl and Mr. Rokicky – sometimes two or three a week – containing the names, personal details and photographs of Jews trapped in occupied areas and in need of fake passports.

Rodolfe Hugli, the honorary Paraguayan consul to Switzerland, also played a vital role – though a controversial one, because of the profit he made. Mr. Hugli sold blank Paraguayan passports to the network, then affixed his official stamp to the documents after Mr. Kuhl and Mr. Rokicky prepared them.

Some of the documents were collected by Mr. Blechner, while others were assembled by diplomats currently stationed at the Polish embassy in Bern.

While many details of the passport-smuggling operation have become public over the decades, the scale of the Polish legation’s involvement was not publicly known until now. Nor was Mr. Kuhl’s Canadian connection.

“It is unfortunate to note that some officials of the Polish Legation were very closely mixed up in this affair,” reads a 1943 Swiss police document that lays out the scheme and its participants. “Mr. Julius Kuhl was repeatedly given Paraguayan passports by Mr. Hugli, which he then took to the Polish Legation, where the names of Polish Jews were entered [into them], although [the recipients] had no claim to the possession of such papers.”

Several documents demonstrate that the entire effort took place with the active assistance and protection of Aleksander Lados, Poland’s de facto ambassador at the time.

It was Mr. Lados who had hired Mr. Kuhl and – despite increasing pressure to dismiss his deputy consul – gave his activities diplomatic protection.

(The government-in-exile of Nazi-occupied Poland had diplomatic representation in Bern via the same building that now houses the country’s embassy here. The Swiss government granted Mr. Lados and his colleagues diplomatic status though Switzerland but, to avoid provoking the Nazis, never formally accepted Mr. Lados’s credentials as Poland’s ambassador.)

“The Polish Legation in Bern, wishing to save its citizens, is doing all it can,” reads an August, 1943, letter from Mr. Silberschein, the man who compiled the lists for Mr. Kuhl’s network, to Archbishop Bernardini. “Thanks to these means, a few thousand lives have been saved.”

“Mr. Lados was the head and he tolerated and protected what Mr. Kuhl did,” said Mr. Blechner, who believes Mr. Lados should be added to the Righteous Among the Nations, an honour bestowed by the state of Israel on non-Jews who risked their own safety to rescue Jews from the Holocaust.

The possibility of obtaining a Latin American passport was a ray of hope for those trapped in Nazi-occupied Poland.

“I’d like to have Uruguayan passport, Costa Rican, Paraguayan – just so one can live peacefully in Warsaw, after all, it is the most beautiful of lands,” wrote Wladislaw Szlengel, a poet who lived in the Warsaw Ghetto until he was executed in May, 1943.

As the pace of the killings accelerated, so did the secret passport operation – until Swiss police broke it up.

Police records show Mr. Silberschein and his colleague Penny Hirsch were arrested in September, 1943, and found to be in possession of an assortment of Latin American passports, as well as several foreign currencies.

Under interrogation, the Moscow-born Ms. Hirsch told police she was aware of “between 200 and 300 passports” that had been distributed to Jews living in German-occupied parts of Europe. She told the police that she and Mr. Silberschein knew they had been breaking the law but that their motivations were purely humanitarian. “We did not intend to harm Switzerland,” she added, according to a police transcript.

While American Jews provided financial support to Mr. Kuhl and his network, the U.S. government was less helpful – apparently out of concern that German spies might reach North and South America using the passports. “The Legation of the United States in Bern, informed the Polish Legation some time ago that it was not satisfied with this traffic in passports,” Mr. Silberschein said during his own interrogation by Swiss police.

He said the network paid anywhere between 550 Swiss francs for a blank Haitian passport and 1,200 for a Paraguayan one. (The average hourly wage at the time was less than two francs.)

But when asked how many passports he had helped smuggle in, Mr. Silberschein claimed not to know. “I don’t have a very good memory for numbers,” he told the police.

By the fall of 1943, Swiss police had focused their investigation on Mr. Kuhl, and Mr. Lados was summoned by the Swiss Foreign Ministry to explain the activities of his diplomat.

Mr. Lados swung between pleading with the Swiss – telling them the passport scheme had been motivated by “the desire to save the lives of many good people” – and subtly threatening to expose how Swiss police had themselves granted stateless passports to Jews crossing the country on their way toward neutral Portugal and Spain.

Mr. Lados and Mr. Kuhl remained in their posts until September, 1945, when they were replaced by emissaries from Poland’s postwar Communist government.

Stripped of his diplomatic status, Mr. Kuhl was told that, despite having a Swiss wife and two Swiss-born children, he had to leave Switzerland. He moved to Toronto with his young family “because the Canadians would have him. Jewish migrants were not welcome everywhere,” Mr. Singer said, adding that his father-in-law also tried living in New York but “felt lost” there.

“Toronto’s Jewish community was very welcoming to immigrants. He found his Judaism renewed in Toronto to a degree that never would have happened to him in Switzerland,” Mr. Singer said. “He arrived with a briefcase full of watches and became an important businessman and a Canadian citizen.”

Mr. Kuhl remained in Toronto until 1980, when he moved to Miami. By that point, he was already suffering from the emphysema that would claim his life.

A curiosity among the documents seen by The Globe is a 1960 letter Mr. Kuhl received from Roland Michener, then a Progressive Conservative MP and the Speaker of the House of Commons.

“It is indeed a remarkable story of which you have reason to be proud,” wrote Mr. Michener, who would become Canada’s 20th governor-general. But Mr. Michener appears to have been referring to Mr. Kuhl’s career in the construction industry, not his life-saving efforts during the Holocaust.

Mr. Singer says that while Mr. Kuhl never saw himself as a hero, it’s time his father-in-law was acknowledged as such.

“My view is that Dr. Kuhl was in the right place at the right time, and instead of doing nothing – like most people – he did the right thing.”

MARK MACKINNON

BERN, SWITZERLAND

THE GLOBE AND MAIL

LAST UPDATED: TUESDAY, AUG. 08, 2017 6:56AM EDT