After lighting the torch to open the 1996 Olympic Games in Atlanta, Muhammad Ali receded from the public eye.

He’d been vanishing for years. The patter was gone, replaced by silence and a worsening tremble. No man had been so full of vigour and none was harder to watch as it deserted him.

In the intervening two decades, something peculiar happened. Mr. Ali, the great sportsman and rabble-rouser of the 20th century, became instead its exemplary citizen.

He was, like all of us, a complicated and contradictory person. Somehow, those contradictions accumulated into a man who defined his age.

Wherever we all were when he was born in backwater Louisville during the height of the Second World War and wherever we are now that he has died, at the age of 74, the arc of his life traced the arc of history. It is a testament to Mr. Ali that, from this vantage, it is hard to say which is which.

At the height of his powers in the 1960s, Mr. Ali was a divisive figure in his native United States.

He had at first embraced America’s ideal image of itself – winning a boxing gold medal in at the 1960 Rome Olympics, scolding the Soviets for their weakness and dominating what was still then the sport of kings.

When he then rejected the country of his birth – switching Christianity for Islam, changing his name, spurning integration and refusing to sign on for the war in Vietnam – the insult was felt all the more keenly. Because even the worst of America could see that Mr. Ali was the best of them.

The secret was a brand of charisma that could push and pull at the same time. Even while Mr. Ali was berating you, finger jabbing into the nearest camera, he could make you feel special. Even his coldness had warmth.

Celebrities could feel it. They lined up at his door, hoping to receive either a blessing or a curse. Mr. Ali was almost certainly a narcissist – any other sort of person would have collapsed under all the attention – but a generous one.

He wanted everyone to feel his touch, however briefly. He signed so many autographs in his lifetime that the mark of the greatest athlete of all time has been rendered nearly valueless through sheer volume. That is, if we are speaking in terms of money.

No one would have known him or cared if he hadn’t been able to fight. His record is excellent, but not jaw-dropping – 56-5, with 37 knockouts. He was world champion three times.

The first of those titles cemented his legend – the defeat of Sonny Liston, America’s own bogeyman.

Everyone thought Mr. Ali (then still called Cassius Clay) would lose. L.A. Times columnist Jim Murray wrote, “The only thing at which Clay can beat Liston is reading the dictionary.”

But Mr. Ali couldn’t stop telling people how easily he would win. He mocked Mr. Liston as a “big, ugly bear” and said he would donate him to the zoo. Later, Ali would say, “[Liston] couldn’t see nothing to me at all but a mouth.”

He won that fight, but few hearts. White America didn’t appreciate the bravado, but it would not forget the confidence.

There were more and better fights as Mr. Ali refined his style. He eventually proved he could lose more magnificently than anyone before.

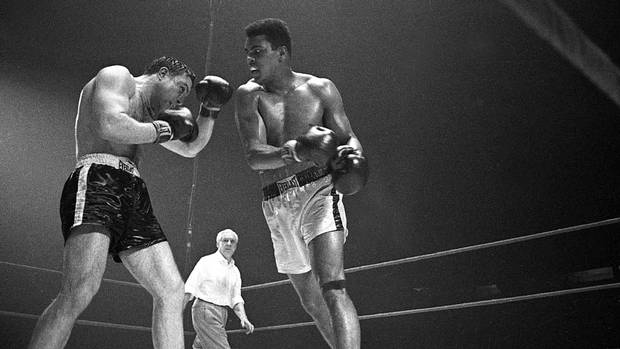

Having missed him at his best, most of us have to take the word of a generation of defeated opponents and chroniclers of the sport as to his greatness. Looking back at the black-and-white tapes, he doesn’t look like all that much. Too lithe for a heavyweight, moving too easily for a 200-pound man. There is no seeming power in his jabs; they look like exploratory pokes.

But there were so many of them, and Mr. Ali himself never seemed to get hit. The current sporting zeitgeist values power. Watching Mr. Ali reminds us that visionaries take something difficult, turn it to one side and suddenly it is easier. He was unique in his grace.

As Mr. Ali became more and more famous for boxing, boxing became less important for him. By the seventies, he was perhaps the most recognized face on Earth. Having split with America, he turned elsewhere for support and backing. He received it universally.

In talking about Mr. Ali it is difficult to avoid clichés, since he established so many of them. He was the first global sports star and the first public figure that transcended culture and language. He has many imitators, but no successors. Those who came after him are salesmen and women promoting products. They are distant figures.

Mr. Ali was intimate. He went everywhere. He embraced everyone. He wasn’t trying to sell anything. He needed to be loved and to be seen to be loving back.

He seemed just as happy surrounded by village children as he was cozying up to U.S. presidents. Not ‘happier,’ but just as happy. Mr. Ali liked people and liked people to like him. It is an irresistible combination. He made no distinctions between them, neither up nor down.

Perhaps this was the poet in him. I think that in the fullness of time, that is how he will be best remembered – for his verses, his remarkable doggerel and general ability to electrify crowds with his verbal acuity.

There is more joy in watching video of Mr. Ali rhyming than in watching him beat another man. That will last.

His legacy is too vast to fully contain in any memorial. He changed the world by changing the way people see themselves in it. He reshaped and exported the American dream. He made everything feel more possible, more mutable. No man has ever been more famous for being kind. That lasts, too.

Time strips away memory until only its most basic elements remain. What happened in the 18th century? Voltaire happened. What about the 19th? Darwin, Marx and Napoleon.

When people think about the 20th century centuries from now, they will only think a few things. One of them will be Muhammad Ali.

CATHAL KELLY

The Globe and Mail

Published Saturday, Jun. 04, 2016 10:58AM EDT

Last updated Monday, Jun. 06, 2016 12:16AM EDT