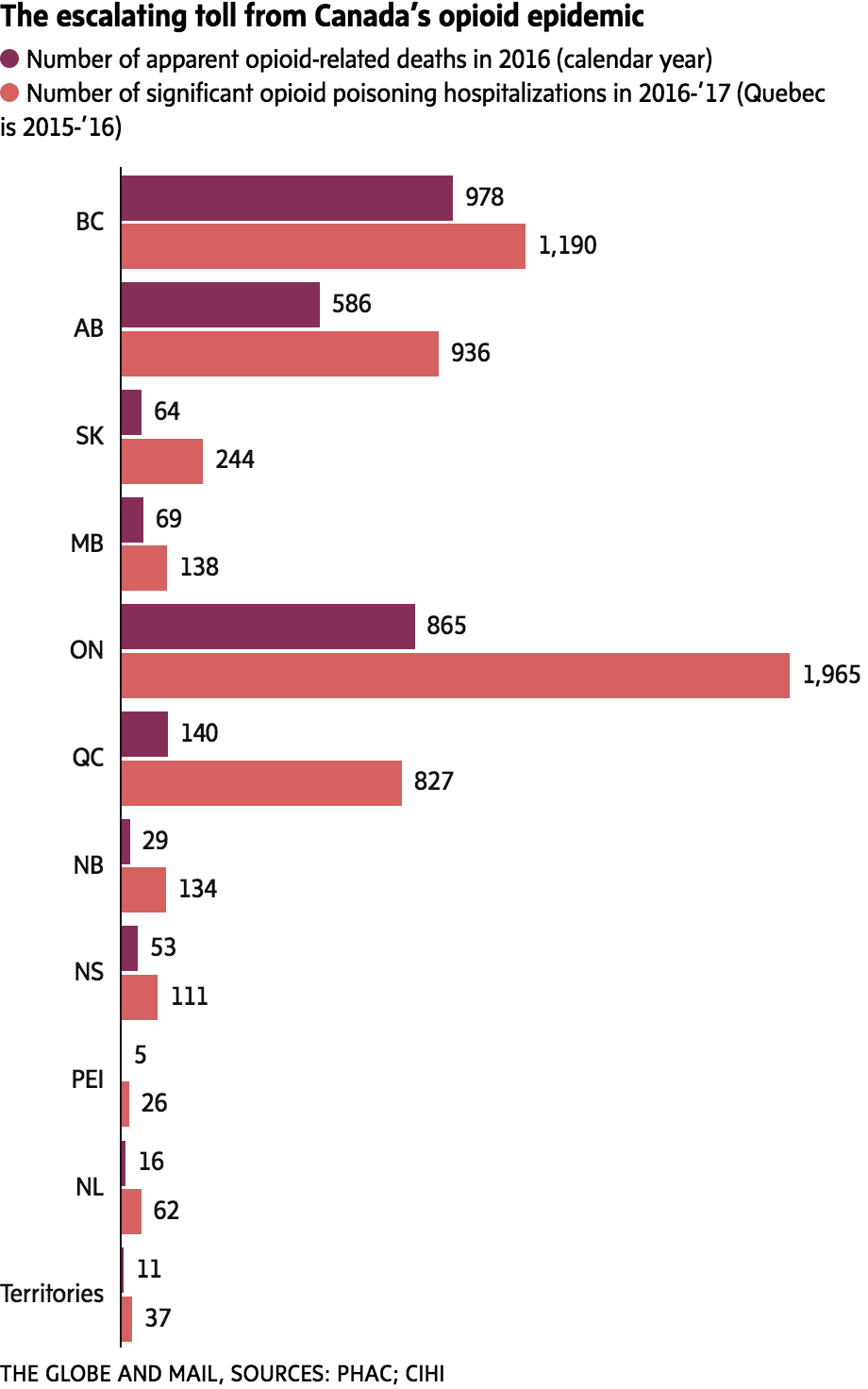

Prescription painkillers and illicit fentanyl are together fuelling a national epidemic of opioid-related overdoses, claiming the lives of more than 2,800 people in Canada last year, new figures show.

The crisis is affecting every region, according to the first complete national snapshot of opioid-related deaths for 2016.

Canada’s chief public health officer Theresa Tam said the grim statistic, unveiled on Thursday, represents an average of eight people dying every day. She said the Public Health Agency of Canada plans to deploy epidemiologists to the provinces and territories to help gain a better understanding of regional variations.

“No area of Canada is necessarily safe from this crisis,” Dr. Tam told reporters at a technical briefing in Ottawa. “Everybody needs to be prepared.”

Street drugs, including illicit fentanyl, accounted for a large proportion of overdose deaths in Western Canada, the region hardest-hit by the crisis, but they are not as big a problem in Atlantic Canada, Robert Strang, Nova Scotia’s chief medical officer of health, said during the briefing. In Alberta, fentanyl accounted for 64 per cent of opioid-related deaths in 2016. In Nova Scotia, by contrast, 15 per cent of deaths involved fentanyl, leaving the vast majority linked to prescription painkillers, including pharmaceuticals diverted to the street.

“We are facing two different but overlapping issues: first, overdose deaths from prescription opioids and second, overdose deaths from illicit drugs laced with fentanyl or other synthetic opioids,” Dr. Strang said. “There is no single solution to this crisis.”

A continuing Globe and Mail investigation has found that federal and provincial governments across the country did not do enough to forestall the rise of an epidemic rooted in the overprescribing of powerful painkillers such as oxycodone, hydromorphone and fentanyl.

The crisis has deepened with the arrival in Canada of illicit fentanyl, a synthetic opioid that street dealers are cutting into illegal drugs, primarily heroin and cocaine.

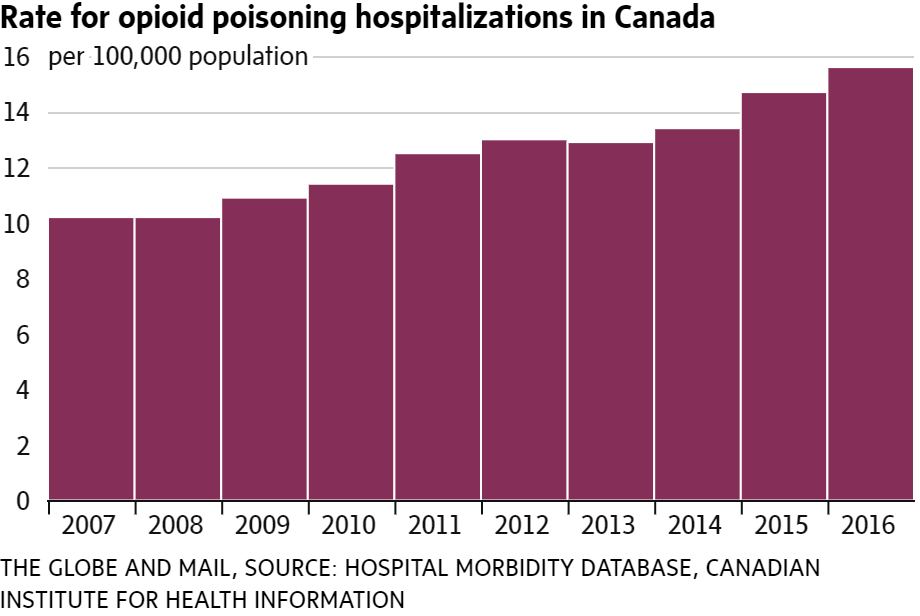

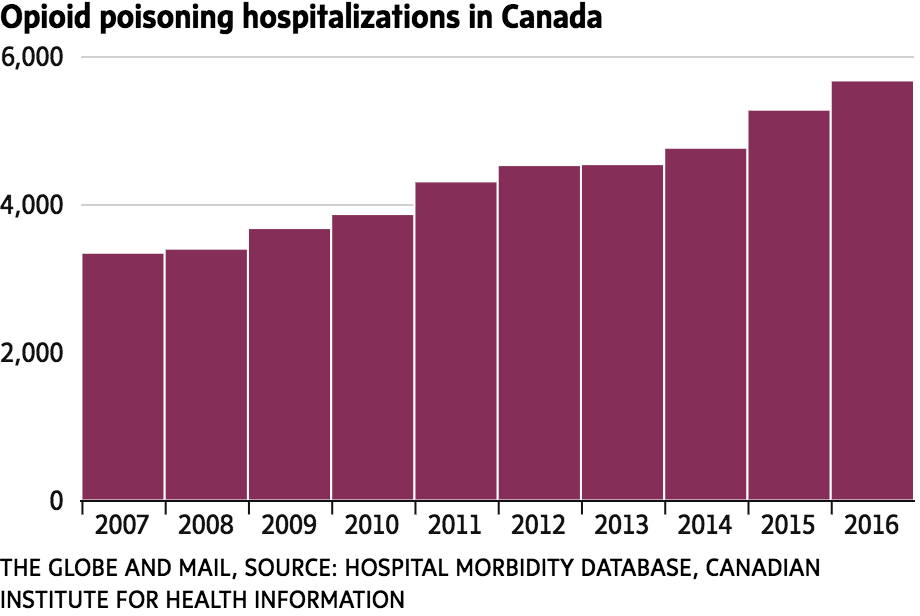

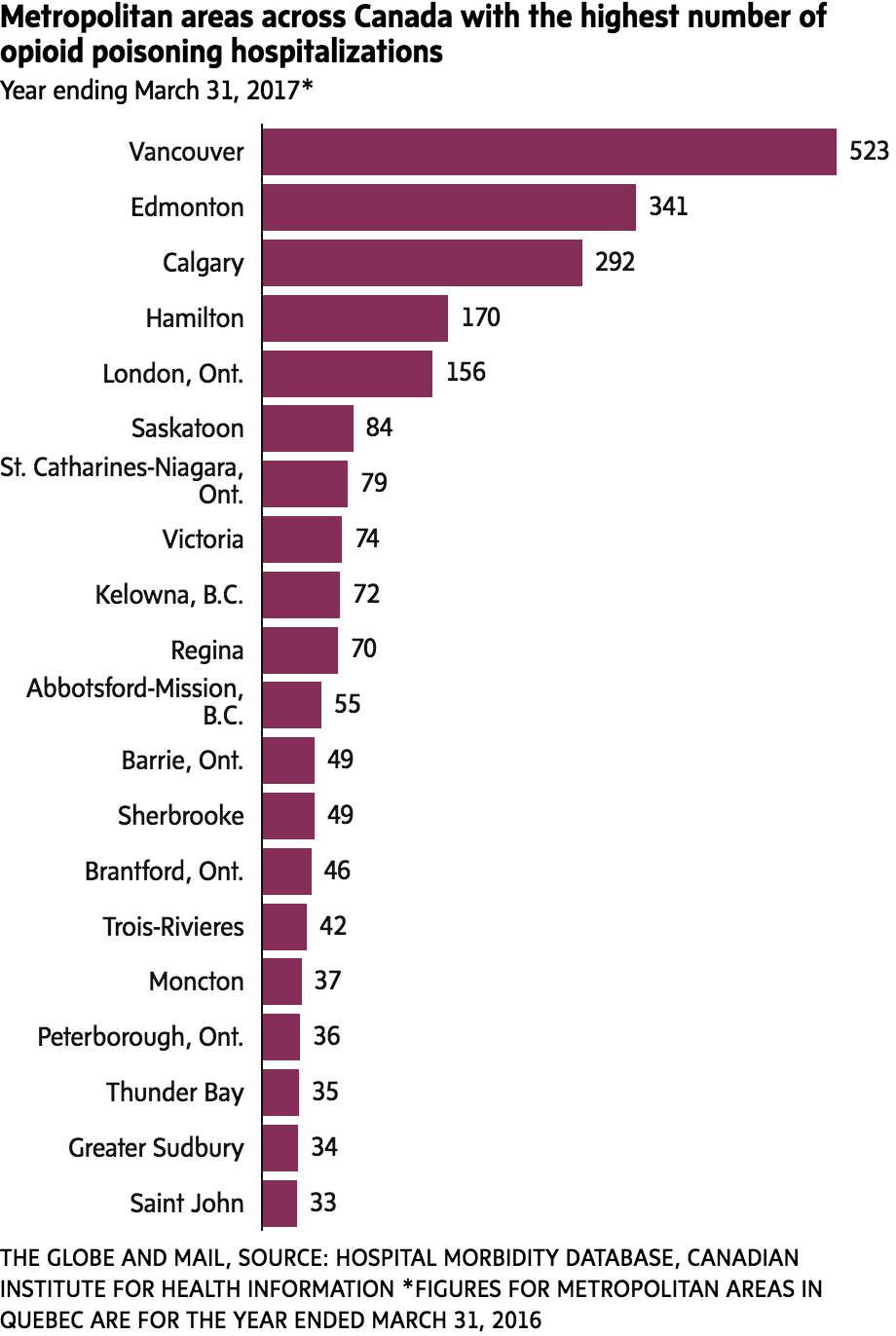

Another measure of the toll the epidemic is taking is the number of admissions to Canadian hospitals for opioid overdoses, accidental or deliberate, which increased by 70 per cent over the past decade.

An average of 16 people a day were admitted to hospital in 2016-17, according to new figures from the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI), released on Thursday. Hospitals across the country logged 5,670 admissions for inpatient care related to significant opioid poisoning in 2016-17, up from 3,344 in 2007-08. Those patients stayed in hospital for an average of 7 1/2 days. The figures do not include people treated in emergency departments and sent home.

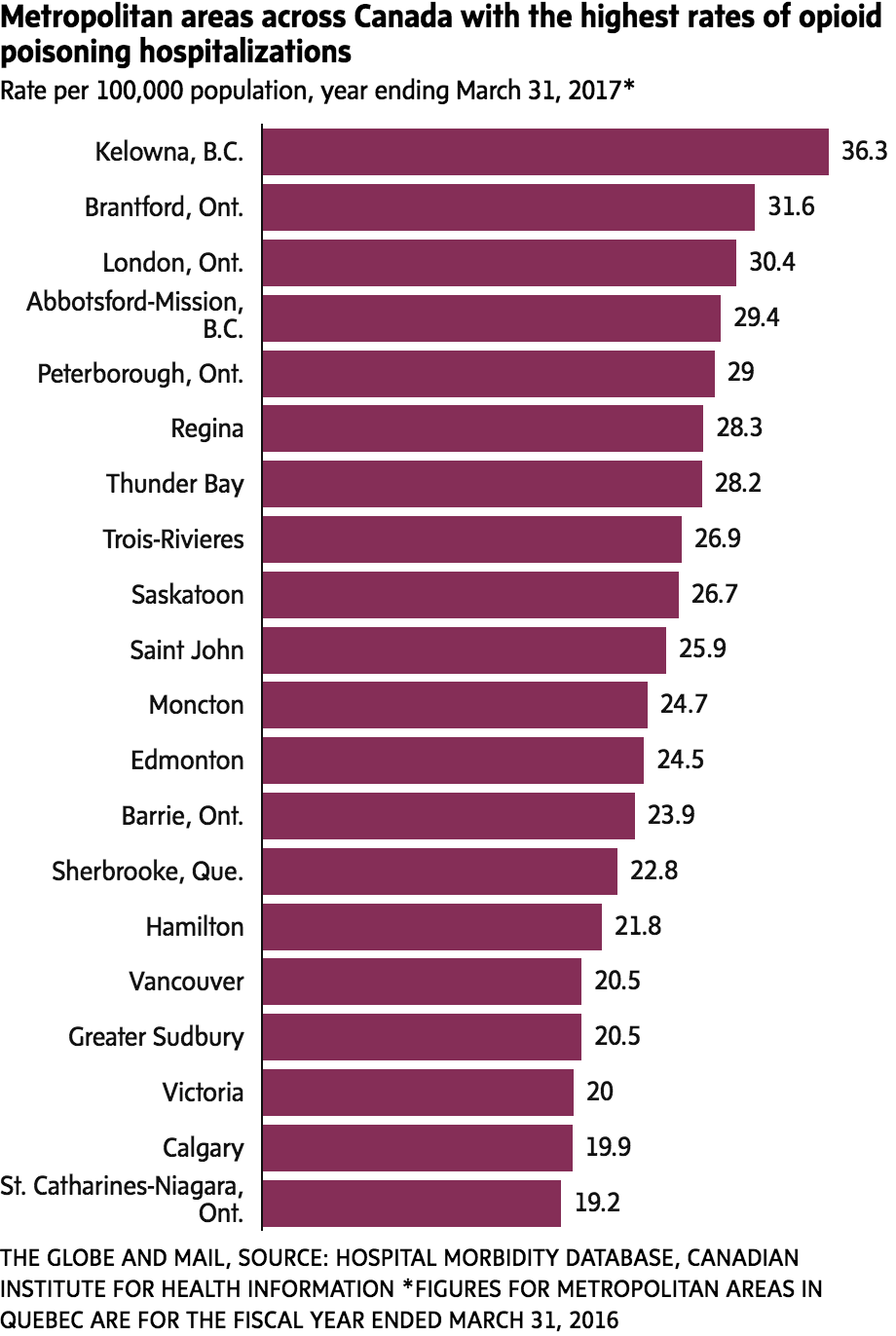

The CIHI report also reveals that the crisis is much more than just a big-city phenomenon. Smaller cities, including Regina, London, Ont., and Moncton, were among those with the highest rates of hospitalizations owing to opioid poisoning in 2016-17, based on population.

By comparison, Toronto, the country’s largest city, ranked second-lowest on a list of 34 metropolitan areas with a rate of 7.9 hospitalizations for every 100,000 population. Vancouver, a city in a province at the epicentre of the crisis, ranked in the middle of the pack with a rate of 20.5. Montreal was in last place.

Kelowna, in British Columbia’s picturesque Okanagan region, had the highest rate of hospitalizations due to opioid poisoning in 2016-17. The rate was 36.3 for every 100,000 population.

Dr. Trevor Corneil, chief medical health officer for Interior Health, a regional health authority in British Columbia that includes the city of Kelowna, said he first identified a spike in fatal and non-fatal overdoses in late 2015. Unlike Vancouver, where much of the fentanyl problem is concentrated in the Downtown Eastside and out in the open, his research has found that many people in smaller regional cities like Kelowna tend to use drugs at home, making them more difficult to find and to treat, Dr. Corneil said in an interview. That is one reason why more people in smaller cities end up in hospital, he said.

To try to help those people using drugs at home, Interior Health began operating a mobile supervised drug-use service in April in Kelowna. The mobile unit travels to neighbourhoods that are known “hot spots” for drug use.

The challenge for policy makers across Canada will be tailoring interventions to address both prescription and illicit opioids, Dr. Strang said. Quebec Health Minister Gaétan Barrette announced on Thursday that his province will follow the example of several others and offer the opioid antidote naloxone free of charge and without a prescription in Quebec pharmacies.

Dr. Strang said more supervised drug-use sites are needed for street drug users so people can consume safely. The federal government has approved 17 new sites across Canada.

Dealing with prescription opioids is more complicated, he said, because that involves reversing two decades of overprescribing. Patients currently on high doses of prescription opioids could be at risk of turning to illicit drugs if their doctors cut them off, he said.

“We have a lot of work to do to change how opioids are prescribed,” Dr. Strang said.

KAREN HOWLETT

The Globe and Mail, September 15, 2017