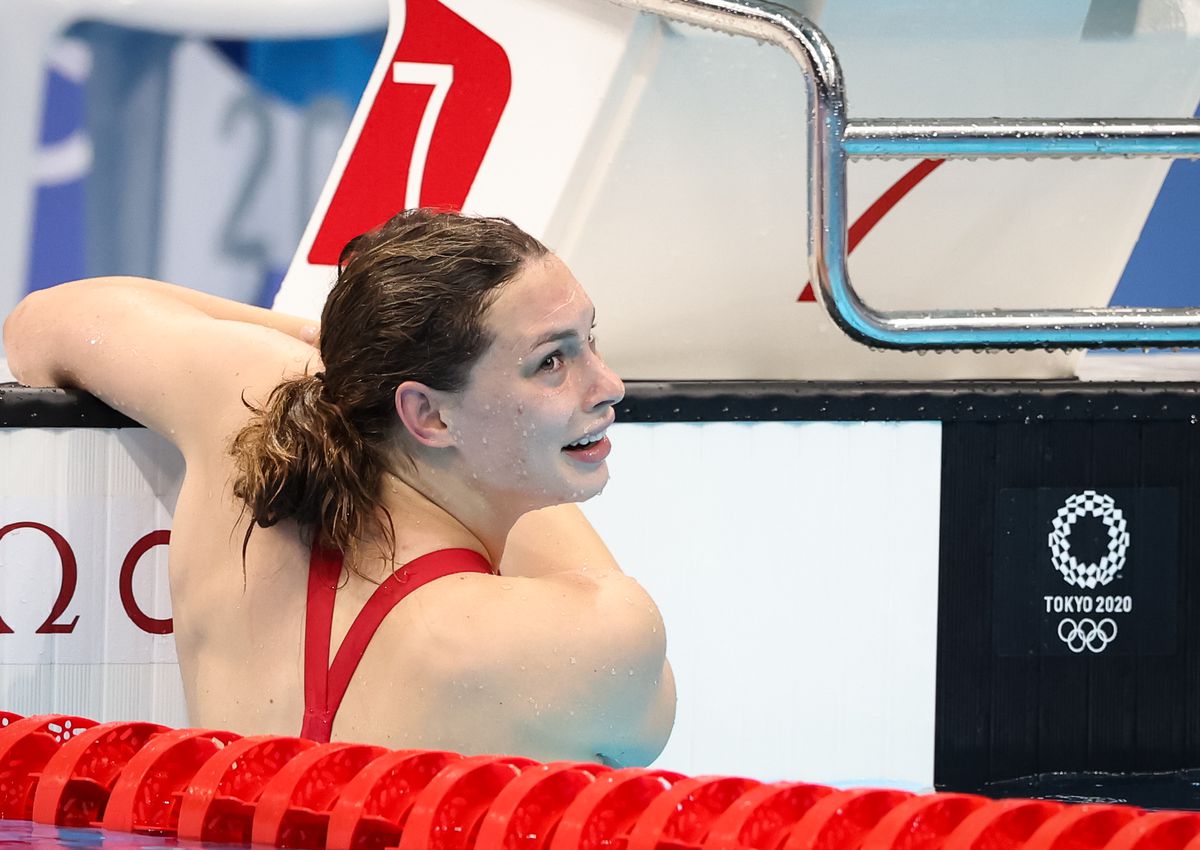

Penny Oleksiak celebrates after winning the bronze medal in the women’s 200m freestyle at the Tokyo Aquatics Centre at the Tokyo Olympics on July 28, 2021. The result made her Canada’s most decorated summer Olympian. MELISSA TAIT/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

Standing there right after becoming Canada’s most-decorated Summer Olympian, Penny Oleksiak has to give some real thought to why she’s so good at the Games.

The inference is that she isn’t quite so great everywhere else. Not that she’s bad. Just not six medals in seven finals good.

“I love, like, pressure a little bit,” Oleksiak said, dipping her head slightly as if to duck a blow. “When I know it counts, I know I’m able to show up for it.”

She was more unfiltered in her TV interview straight out of the pool after her bronze medal in the 200m freestyle.

“(Teammate) Maggie (Mac Neil) came in today with her gold medal and I’m staaaaaring at it,” Oleksiak purred. She put so much guttural emphasis on the key word, the short-a sounded more like a short-e.

Oleksiak is great at swimming for a bunch of reasons. Her genetics, her dedication, the quality of her training, luck.

But what puts her that definitive inch above her contemporaries is covetousness. Oleksiak covets greatness. She wants to be the best when it matters most. Not her best. The best.

“I just love the Olympics,” Oleksiak said. “Just knowing that the whole world is watching is super crazy.”

One of the running themes of this still-young Olympics has been pressure. Simone Biles, the face of the Games, cited pressure as the reason she dropped out of the gymnastics team event on Tuesday. Japan’s brightest star, Naomi Osaka, referenced it after dropping an early match to the 92nd-ranked player in the world.

There’s no question that today’s top athletes are under far more of it than their predecessors were even 10 years ago.

A decade ago, stars who didn’t enjoy constant attention could hide from it. This was especially true for Olympians.

You’re the very, very best in the world at, say, the 400m freestyle? You’ll be hounded at the Olympics – and largely ignored for the three-and-a-half years between them.

Social media changed that calculation. Today’s stars must be constantly virtually present or risk losing relevance. All the good stuff you hear about yourself on there must be nice, unless it gets in your head. The sheer volume of bad stuff must be soul-crushing, and that will absolutely get in your head. It’s a lose-lose.

Ms. Oleksiak looks up at her results after swimming to take the bronze medal in the women’s 200m freestyle. MELISSA TAIT/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

Famous Olympians are now especially prey to this calculus because they have to make hay while the sun shines. Performing at the Games is the key to monetizing the next four years.

When you do show up, the weight of the world is laying across your shoulders. This is your one shot to justify all those magazine covers.

If you win, well, that’s what you were supposed to do, so great. You’re still in the in-crowd.

If you lose, you’re a has-been or, worse, a fraud.

Imagine knowing that you will be the focus in every room you walk into, whether there are a dozen people in there or 20,000. Imagine every one of them has a fixed idea about who you are, what you’re about, and what you must do in order to walk back out with your head up.

It’s an impossible ask which we, the viewing public, have been asking over and over for decades.

Only a particular sort of person would think of that as fun. Apparently, Oleksiak is one of them.

This love of pressure and a sort of bloody minded determination to prove people wrong isn’t a prerequisite for athletic greatness. But it’s clear that it is an advantage, and growing more so as athletic stardom becomes more fraught.

One of the things that will doubtless come out of the Tokyo Games is a wider discussion of how and why the developed world lost the collective plot when it comes to sports. Believe it or not, there was a point in history where it was more impressive to have a good office job than throw things for a living.

Youth sports tipped over into performance hysteria years ago, but the result of that is only beginning to show itself at the elite level.

If youth sports are the Earth, there’s a meteor headed its way called proportion. A small sense of proportion will radically alter the landscape of children’s sport. I’m not convinced it will happen – it would cost a lot of people a lot of money – but it will at least get discussed.

In the interim, that creates a performance wedge for the unusual few – I won’t say ‘lucky’, because they make their own luck – who crave that pressure. For the ones who want to be great, despite the noise.

In her quiet way, that’s Oleksiak.

The 200m free is not her race. Coming into this session, she was a second or two off the best in the world. She set her low time in the prelims for the final. Then she did it again while everyone was watching her.

For the rest of us, it’s like imagining we can fly a plane because we’ve seen it done on TV, and then landing one in real life.

How does Oleksiak explain that?

Not for the first time, she shrugged: “I wanted a medal.”

CATHAL KELLY

The Globe and Mail, July 27, 2021