The Bank of Canada is upgrading its outlook for Canadian growth in anticipation of billions of dollars in new federal stimulus cash.

But Governor Stephen Poloz remains surprisingly glum about what’s ahead as he weighs a range of unpredictable and volatile crosswinds, including a resurgent Canadian dollar, the continuing investment free fall in the oil patch and China’s slowdown.

“The global economy retains the capacity to disappoint further,” Mr. Poloz warned Wednesday following the central bank’s decision to keep its key interest rate unchanged at 0.5 per cent.

Some economists said Mr. Poloz is being hyper-cautious after serial disappointments and false dawns for Canada’s economy over the past couple of years.

“The bank is just being prudent,” said Carl Weinberg, chief economist at High Frequency Economics in Valhalla, N.Y. “The data aren’t sending a clear signal. So they’re watching, and that’s the right thing to be doing.”

Others, however, see another possible motive in the pessimism of the normally sunny Mr. Poloz – discouraging a further rally in the currency, which has gained 15 per cent since early last fall to just above 78 cents (U.S.).

“We see this as jawboning – an attempt to prevent the Canadian dollar from strengthening even as they upgrade growth,” according to a Merrill Lynch research note.

Bank of Montreal chief economist Douglas Porter said Mr. Poloz is trying to walk a fine line between a brighter forecast and the strengthening currency.

“They appear to have threaded the needle by maintaining and even ramping-up the caution on the underlying growth outlook,” Mr. Porter said.

The prospect of faster growth likely puts a rate cut on the shelf and could move up an eventual return to higher rates, according to several analysts.

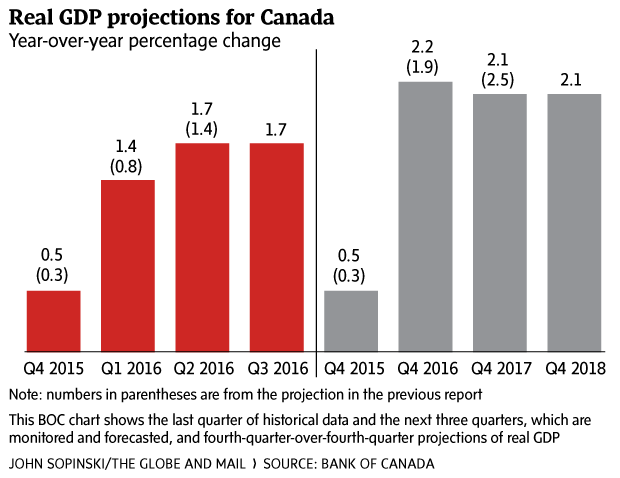

The central bank said measures from last month’s federal budget – including roughly $25-billion of new money over two years for infrastructure and families – will boost gross domestic product by 0.5 per cent this year and 0.6 per cent in 2017. The bank now expects growth of 1.7 per cent this year and 2.3 per cent in 2017, compared with estimates of 1.4 and 2.4 per cent, respectively, made in January.

“The effects of recently announced fiscal measures will begin to be felt in 2016 and will build through 2017,” the bank said in its latest quarterly Monetary Policy Report.

Without that infusion, the bank said it would have downgraded its outlook from its January forecast. Were it not for the budget, Mr. Poloz told reporters, another rate cut might have been on the table heading into this week’s central bank meeting.

“Our risks are two-sided and so is our policy,” Mr. Poloz told reporters.

The bank’s forecast of 1.7-per-cent growth this year is significantly better than the 1.4 per cent built into Finance Minister Bill Morneau’s recent budget projections. But it’s several notches below many private sector economists, who now expect the economy to grow 2 per cent or better.

The bank said growth in the first quarter “appears to have been unexpectedly strong” and is “likely to reverse in the second quarter.” GDP growth surged ahead 0.6 per cent in January, surprising many economists, and the bank now expects growth in the quarter to hit an annualized 2.8 per cent.

“Some of the strength is due to temporary factors,” the bank pointed out.

The bank said that while exports outside the resource sector are growing again, their impact is being held back by the bounce-back in the value of the Canadian dollar and the sluggish global economy.

Working against the Canadian economy are several powerful forces, including a slower-than-expected recovery in the global economy and tumbling investment in the battered oil and gas sector. The bank now expects investment in the oil patch to be 60 per cent lower this year than it was just two years ago as energy companies continue to slash spending.

The bank said the “profile” of the U.S. recovery is also having a more muted effect on Canadian exports, in part because of lower-than-expected housing starts and surprisingly weak investment in the energy sector.

The bank also downgraded the economy’s potential to grow over the longer term and it may remain impaired for some time due to weaker labour productivity, lower investment and the aging of Canada’s work force (1.5 per cent annually from 2016 to 2018 and 1.6 per cent in 2019 and 2020, down from a previous estimate of 1.8 per cent annually over that period). The central bank has been regularly downgrading Canada’s growth potential since the 2008 financial crisis.

BARRIE MCKENNA

OTTAWA — The Globe and Mail

Published Wednesday, Apr. 13, 2016 10:05AM EDT

Last updated Wednesday, Apr. 13, 2016 6:51PM EDT