If Canada is to meet its commitments for conservation under a recently adopted international agreement, it will need to do more than protect intact wilderness areas that have been minimally affected by human activity.

The United Nations agreement, reached in Montreal last December, also calls on participating countries to restore 30 per cent of lands that have been degraded or fully converted to human use by the end of this decade.

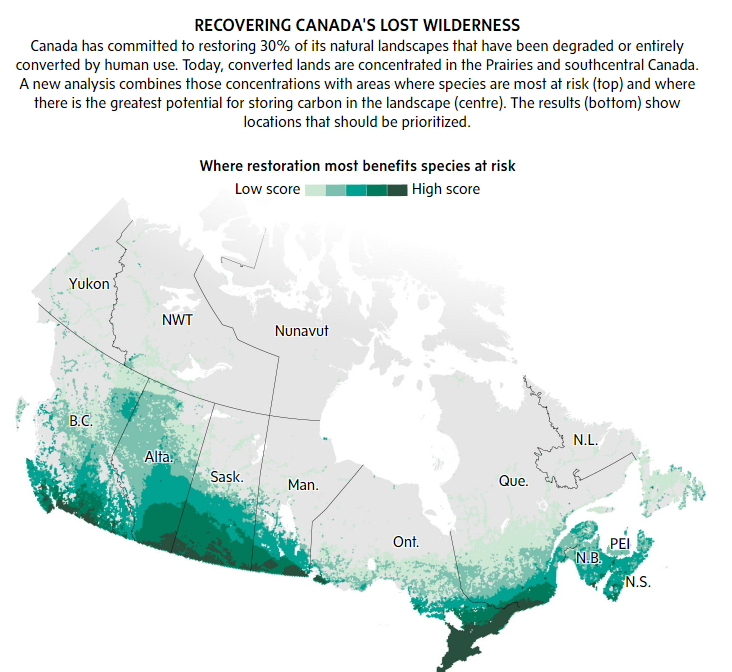

Now a new analysis shows which parts of Canada should be prioritized for restoration to help meet that goal.

The work, led by WWF-Canada, provides an intriguing glimpse at how the country might appear in an alternate reality where the human footprint is much less heavy on the landscape.

“I see it almost like the echo of what it was,” said James Snider, the environmental organization’s vice-president of science, knowledge and innovation. “What we’re saying is if we invest in broad-scale restoration, this is what it could become again.”

The top five things to take away from the UN’s massive, final climate report

The peer-reviewed study, published Tuesday in the journal Conservation Science and Practice, puts the spotlight on a gap in Canada’s planning.

Under the Kunming-Montreal global biodiversity framework – so named because China and Canada led and hosted the meeting that brought it about – countries have agreed to protect 30 per cent of the world’s land, freshwater and marine areas for nature by 2030. In order to achieve the target in Canada, the federal government has begun setting aside large swaths of mostly pristine wilderness for protected status, often in conjunction with Indigenous groups.

But the global framework also includes a restoration target – also by 2030 – that calls for recovering 30 per cent of lands that have previously been degraded or converted. Ottawa has yet to articulate how it plans to achieve this.

“We need to begin this conversation in Canada,” Mr. Snider said.

In their analysis, researchers with WWF-Canada and collaborating universities tried to identify which areas would most benefit the country’s conservation goals if brought back to their natural state.

The team focused only on converted land – places where the human presence is currently dominant on the landscape. Such areas are easy to spot in satellite data, in contrast to degraded natural land, which is harder to identify and measure.

Urbanized areas that account for where the majority of Canadians live and work were also excluded from the study.

Not surprisingly, converted land is most concentrated in areas of the country where agriculture plays a big role, including the Prairies, Southwestern Ontario, and the lowlands surrounding the Ottawa and St. Lawrence rivers.

The team next considered on which of those lands species are most at risk, both in terms of numbers of species and the degree to which they are threatened. As a separate factor, they calculated the carbon storage potential of converted lands.

In doing so, “we had to look at the land cover that would have existed in the absence of conversion,” said the study’s lead author, Jessica Currie. “That’s a totally new analysis that’s never been done before.”

The team then calculated how much carbon would be in the soil or plants of each converted parcel of land had no disturbance occurred there.

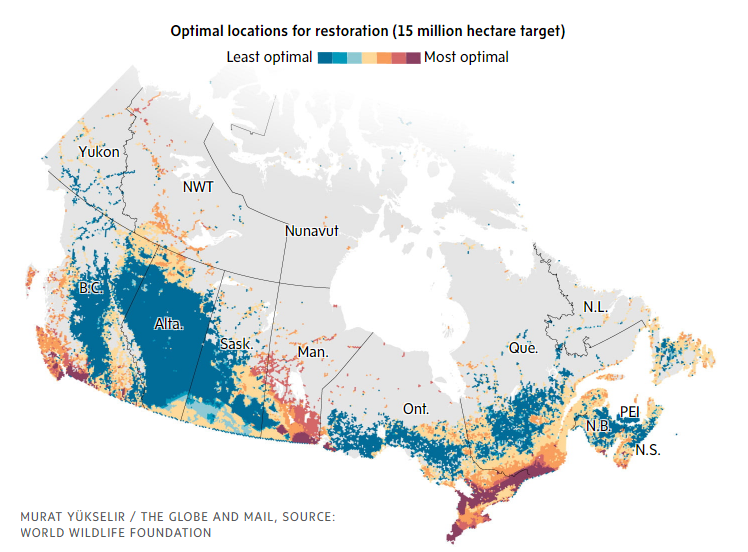

Putting it all together, the results showed which areas offered optimal conservation benefits as a function of how much converted land Canada was aiming to restore by 2030.

Hot spots that consistently turned up in the analysis include British Columbia’s Lower Mainland, the Red River area south of Winnipeg, the southernmost tip of Ontario and the part of Quebec that lies south of Montreal. The presence of wetlands helps account for why these areas in particular rose to the top.

In the most ambitious version of the analysis, with 15 million hectares (150,000 square kilometres) of land restored, the Greenbelt running north of Toronto also figures prominently. The area has lately been a focus of controversy because of Ontario Premier Doug Ford’s plan to allow property development in a portion of the Greenbelt.

While the study does not address the Greenbelt specifically, the analysis suggests that Canada’s conservation targets would be easier to achieve if the Greenbelt remains an undisturbed anchor point around which more restored lands can be added to increase connections between natural spaces for threatened species.

Lenore Fahrig, a landscape ecologist at Carleton University in Ottawa who was not involved in the study, noted that there was a large mismatch between areas whose restoration would maximize species protection and those that would help store carbon, a benefit that will take time to accrue.

“Areas of high combined priority are quite limited,” Dr. Fahrig said. “The question then becomes, would it actually be a good idea to prioritize these overlapping areas?”

She added that land conversion for agriculture remains the main cause of species declines in Canada, which will need to be addressed in order to arrest biodiversity loss.

Many conservation groups, including WWF-Canada, have stressed the need for restoring marginal land that is currently classified as agricultural but not especially productive for growing food.

Mr. Snider said the main goal of the study was to put options before policy-makers for balancing the need to meet conservation targets with other land-use considerations, including housing and food security.

“We need to figure out a clear plan,” he said. “If every decision is made in an ad hoc way then there’s no trajectory for us to meet each of those major societal objectives.”

IVAN SEMENIUK

SCIENCE REPORTER

The Globe and Mail, April 5, 2023