A new report by a group of former world leaders, including ex-prime minister Paul Martin, says fixing our oceans will require unpopular, expensive changes.

The Global Ocean Commission has put forward a report on the declining health of the planet’s high seas, the 64 per cent of the ocean surface that isn’t under the control and protection of a national government. The commission is a combination of public and private sector figures, including former heads of state and ministers as well as business people, supported by scientific and economic advisors working on ways to reverse the degradation of the ocean and address the failures of high seas governance. Their report sets out five main problems, from dramatic over-fishing to rising pollution, and a set of recommendations for reversing the decline.

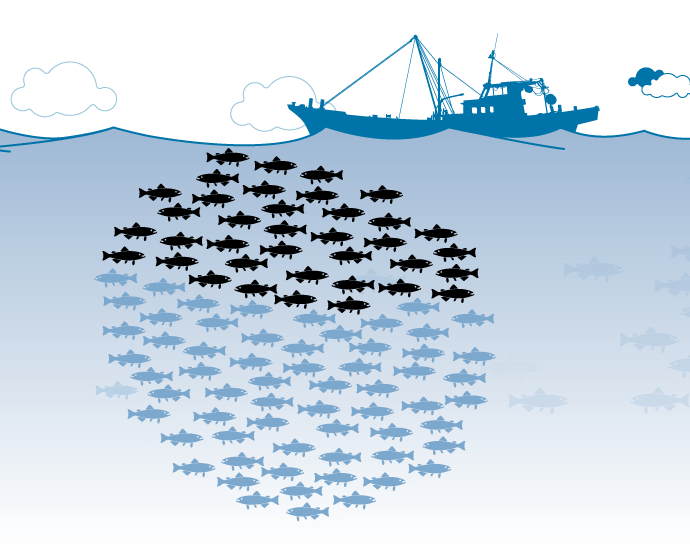

Overfishing

The problem: Technological advancements in fishing equipment along with the growth of illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing has lead to massive overfishing, leaving fish populations at the lowest they’ve ever been. In 1950, only 1 per cent of the fish in the high seas were fished each year and there were no populations that were overfished. By 2006, the number of high seas fish being collected jumped to 63 per cent while a whopping 87 per cent of species were being overfished.

Solution: The Global Ocean Commission recommends capping fishery subsidies to end overfishing and pushing the International Maritime Organization to crack down on illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing through banning fish transfers at sea and cutting market access for illegal vessels.

Text by Kaleigh Rogers, graphics by Tonia Cowan

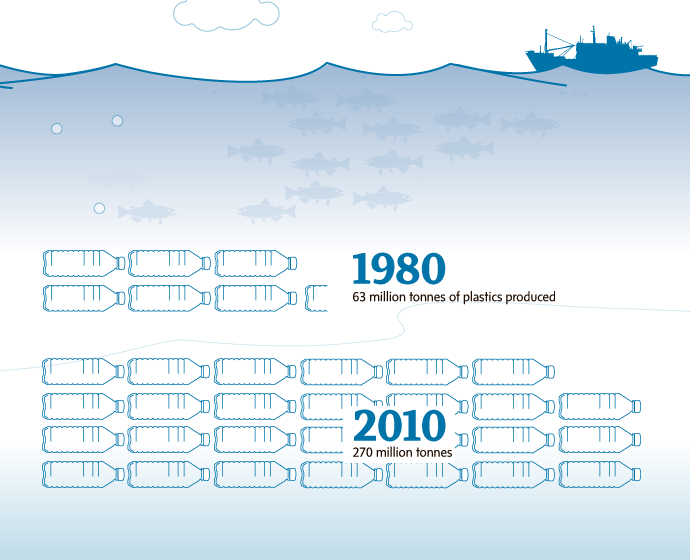

Climate change

The problem: Climate change and pollution have lead to higher water temperatures, reduced oxygen content and increased acidity in the high seas. Though direct impacts are difficult to measure, these changes pose a threat to all ocean life from fish to coral. Plastic pollution, in particular, can lead to microplastics entering the food chain. Plastics production has reached all-time highs: in 1980, the world produced 63 million tonnes of plastics, by 2010 that number had quadrupled to 270 million tonnes and is expected to continue to grow. Since 80 per cent of marine debris comes from land, the increased plastics production is worrisome.

Solution: Through raising awareness and working with governments, the private sector and society at large, the Global Ocean Commission recommends reducing the amount of plastic pollution that makes its way to the high seas.

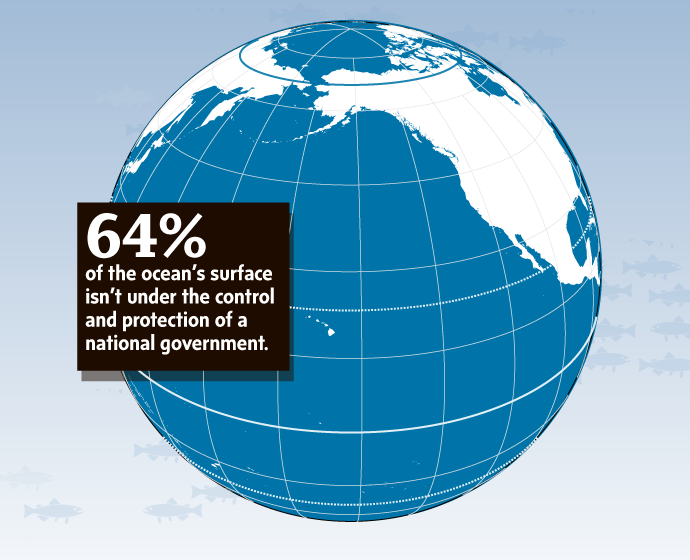

Governance

The problem: For centuries, access to the high seas was limited, so the need for governance was small. Now, the high seas are highly accessible but the world still has a weak, patchwork system of governance for regulations on the high seas. It’s left the oceans with a wild west where rules are neither enforced nor followed effectively. That wild west of the seas encompasses the 64 per cent of ocean surface that isn’t under control of any national government.

Solution: The Global Ocean Commission would like to see a restructuring and strengthening of the international governance structure for organizations overseeing the conservation of the high seas. This structure would be responsibly for updating and ratifying laws universally, as well as establishing an independent Global Ocean Accountability Board to monitor and assess whether or not progress is being made to protect the high seas.

Offshore drilling

The problem: The rising demand for natural resources means a growing amount of the oil and natural gas the world consumes comes from underwater areas. Seismic surveys threaten marine life, gas flaring and venting causes CO2 and methane disturbances and rigs can cause spills in remote waters that are hard to prevent, stop and clean up. Thirty-three per cent of oil and 25 per cent of natural gas consumed in the world come from underwater areas. Offshore drilling is growing in areas like the Arctic, where 30 per cent of the world’s natural gas reserves lie, as well as the Mediterranean Sea and off the coat of East Africa.

Solution: The Global Ocean Commission wants to see strong, global safety and environmental standards for offshore drilling established that cover preparing for spills and liability provisions.

New ocean industry

The problem: Technological developments have opened up ocean access to many other industries, from natural resource extraction to deep-sea mineral mining. It’s also opened up the ability to extract valuable genetic material from marine life that can be used to manufacture everything from food supplements to medicine. The International Seabed Authority has issued 13 contracts to explore for deep-sea minerals over more than 1 million square kilometres of the ocean, with four more pending. Meanwhile, the number of patents for genetic material from marine species has increased at a rate of 12 per cent each year since 1999, with living marine organisms providing components for about 18,000 products.

Solution: The Global Ocean Commission recommends the United Nations create a Sustainable Development Goal for ocean sustainability, including protecting vulnerable areas and marine biodiversity.

A ‘rescue package’ for the fragile ocean system

Former world leaders and ministers from countries around the globe say human activity has put the world’s oceans on a dangerous trajectory of decline and it is time to impose governance on the unclaimed high seas.

The Global Ocean Commission, a body of 18 prominent former politicians and heads of major international organizations, will release a report Tuesday following 18 months of investigation that calls for a five-year “rescue package” for the 64 per cent of the world’s oceans that lie outside national jurisdiction.

Canada is represented on the commission by former prime minister Paul Martin, who was asked to be part of the initiative by commission co-chair Trevor Manuel, the former finance minister of South Africa.

Mr. Martin said in an interview on Monday that it will not be easy to convince countries to take steps that will cause short-term economic pain, but those steps are necessary in the long term to protect regional stability, food security and the integrity of the oceans which the report calls “the kidney of the planet.”

“Inevitably, when you are dealing with the global commons,” Mr. Martin said, “the right thing to do becomes in the economic interests of everybody.”

In the report, a copy of which was obtained by The Globe and Mail, the commissioners say human beings rely on the oceans for clean air, climate stability, rain and fresh water, transport, energy, food and livelihoods. But overfishing, pollution, habitat destruction, acidification and other human activities are pushing the ocean system to the point of collapse, they say.

The report makes eight recommendations, including a call for a new agreement under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea that would impose international governance on the massive expanse of unclaimed waters threatened by “benign neglect by the majority and active abuse by the minority.”

It also wants countries to stop subsidizing fishing outside their own 200-mile exclusive economic zones, to end unregulated and unreported ocean fishing, to stop plastics pollution, to impose legally binding offshore oil and gas extraction standards, and to create areas where industrial fishing would be prohibited.

Mr. Martin says it is critical for the international community to state that ocean recovery is a sustainable-development goal for the United Nations – much like the eight millennium development goals declared in 2000.

There must also be accountability for the progress of ocean remediation in the form of an oversight board made up of scientists and others, he said. “Because, if you don’t measure it, if you don’t keep score, it will fade from the public mind,” Mr. Martin said.

And Canada, he said, has a major role to play. “There is one country that has the longest coastline in the world” and has a large responsibility for the health of the Arctic Ocean in particular, Mr. Martin said. “If we don’t act on the oceans, then all of the riches that exist within the 200-mile limit are going to get frittered away.”

Yes, there will be a cost to protecting the oceans, he said. “But as with so many of these things, the cost is infinitesimally small compared to what the alternative is.”

GLORIA GALLOWAY

The Globe and Mail

Published Monday, Jun. 23 2014, 10:15 PM EDT

Last updated Monday, Jun. 23 2014, 10:23 PM EDT