Human activity, primarily through the use of industrial fertilizers, has nearly doubled the world’s atmospheric concentration of nitrous oxide and made the gas a more significant contributor to global warming than previously thought, an international research team has found.

If emissions of the gas continue to grow at their current rate, it could significantly hamper efforts by countries to meet the goal of the Paris climate agreement, which seeks to limit the increase in global average temperature to less than 2 C above preindustrial levels.

“It’s definitely going to become more important than we had originally bargained for,” said Taylor Maavara, a biogeochemist based at Yale University in New Haven, Conn.

Dr. Maavara is one of more than 50 scientists who contributed to the finding, published Wednesday in the journal Nature. Their report represents the most comprehensive inventory to date of all sources of the gas, both natural and human-caused, as well as the various processes that can remove it from the atmosphere over time.

When compared to carbon dioxide, which is responsible for about three-quarters of greenhouse gas emissions worldwide, atmospheric concentrations of nitrous oxide appear to be minuscule. However, each molecule of the gas is about 300 times more efficient at trapping heat in the atmosphere, so that its overall contribution to climate change is about one-tenth that of carbon dioxide – enough to become a serious factor as emissions rise.

Nitrous oxide is also persistent, lingering in the atmosphere for more than a century, or nearly 10 times longer that methane. And when it breaks down, it creates ozone-depleting byproducts. But because nitrous oxide is difficult to measure in atmospheric concentrations, its effect has been hard to pin down relative to other greenhouse gasses.

The Nature study, led by Hanqin Tian, who directs the International Center for Climate and Global Change Research at Auburn University in Alabama, is part of a larger international project to better quantify and track emissions of the principle gasses influencing Earth’s climate. Dr. Tian said the new result is the culmination of a five-year effort that brought together experts in ocean, forest, soil and freshwater systems, among others, to better characterize the movement of nitrous oxide around the globe.

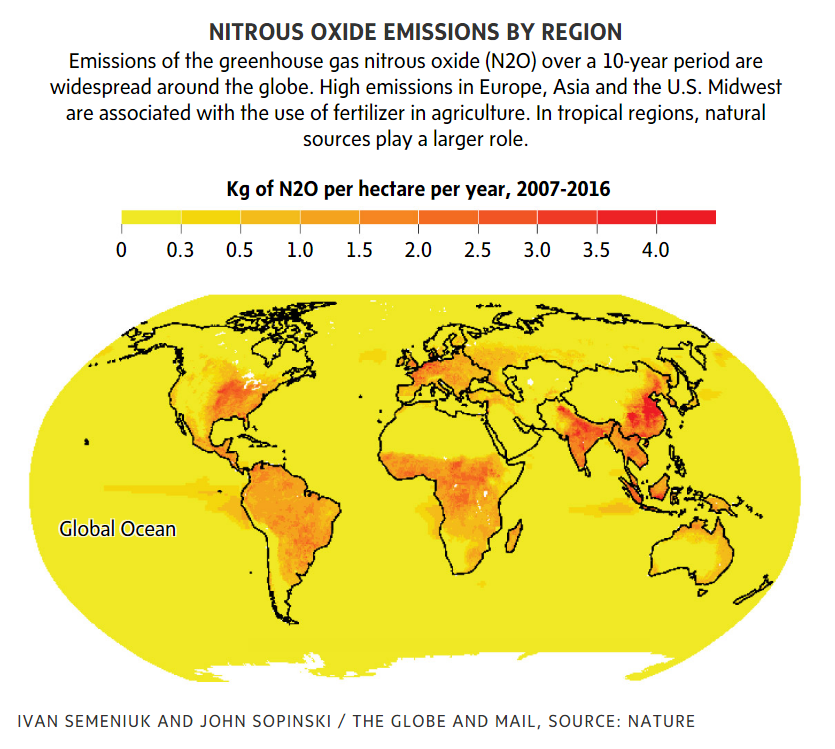

As expected, the study estimated significant natural sources of the gas, primarily from soils and ocean waters with emissions distributed widely around the globe. The study also provided the best estimates so far of smaller-scale emission from inland waters and production of the gas in the atmosphere by lightning.

But more important for climate scientists and policy makers is what the report reveals about human-generated or anthropogenic sources of the gas, when compared to what was previously estimated by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

“The biggest surprise is that the rate of increase is higher than other emission scenarios that have been developed by the IPCC, and that’s a cause for concern,” said Nandita Basu, an associate professor of water sustainability and ecohydrology at the University of Waterloo, who was not involved in the study. “You can really see where the increases are coming from.”

Those anthropogenic emissions include fossil fuel production and deforestation. But the largest source, by far, is the direct application of nitrogen-bearing fertilizers to the landscape. In a regional breakdown of emissions, areas of high fertilizer use, including in Asia, Europe and North America, clearly stand out as hot spots whereas high emissions in tropical regions are driven more by natural sources. Overall, human-caused emissions of the gas have increased by 30 per cent over the past four decades, the report found.

Daniel Pennock, a soil scientist and professor emeritus at the University of Saskatchewan, said the results illustrate the importance of trying to reduce agricultural emissions of nitrous oxide, adding there are several ways to do so without sacrificing crop yields through more efficient use and application of fertilizer.

Dr. Pennock said Canada should be adopting policies that create incentives for farmers to take such measures.

“There’s been a lot of good research in this area but relatively little uptake,” he said, adding that up till now the overapplication of fertilizer has been seen as a relatively inexpensive way for farmers to reduce risk because of weather and other factors.

Darrin Qualman, who represents Farmers for Climate Solutions, a Saskatoon-based advocacy group that formed last year, said there is now a growing awareness and interest within the farming community to change practices, something that is already under way in Europe.

“In general, farmers need to be supported in making a transition,” he said. “We know this is a problem, we know of ways to help solve the problem, but we need government to be a partner.”

IVAN SEMENIUK

SCIENCE REPORTER

The Globe and Mail, October 8, 2020