Growing demand from parents for French immersion has created a shortage of teachers in many parts of the country, with some school boards settling for educators who can speak French only slightly better than their students, according to a new report.

The study released Wednesday by the Office of the Commissioner of Official Languages, which reports to Parliament and whose mandate is to promote bilingualism, found in its survey of school districts that several boards kept language requirements low for fear of not filling teaching positions. One district reported that the linguistic skills teachers demonstrate when interviewing for a position were not always adequate for teaching conversational French and that because of a lack of qualified teaching candidates, some boards felt they had to “settle” for teachers with a slightly better grasp of the language than their students.

The report also found provincial ministries of education expressed concern about a French-language teacher shortage, and suggested positions are being filled, but sometimes with candidates who do not have adequate language or cultural competencies.

French immersion is popular with many parents who want their children to learn a second language or to give them a competitive edge. Enrolment in the program climbed about 20 per cent between 2011-12 and 2015-16, according to Statistics Canada, at a time when the total student body remained the same. Meanwhile, school boards said they have struggled with reconfiguring classrooms and finding qualified teachers.

In its report, the commissioner called on the federal government to work with provinces and territories to encourage greater standardization of teachers’ required French-as-a-second language qualifications, and to implement measures that will support and improve their language proficiency and their linguistic and cultural confidence.

Raymond Théberge, the Commissioner of Official Languages, said in a release that Ottawa should look at establishing a national strategy to address the shortage of French-as-a-second-language teachers.

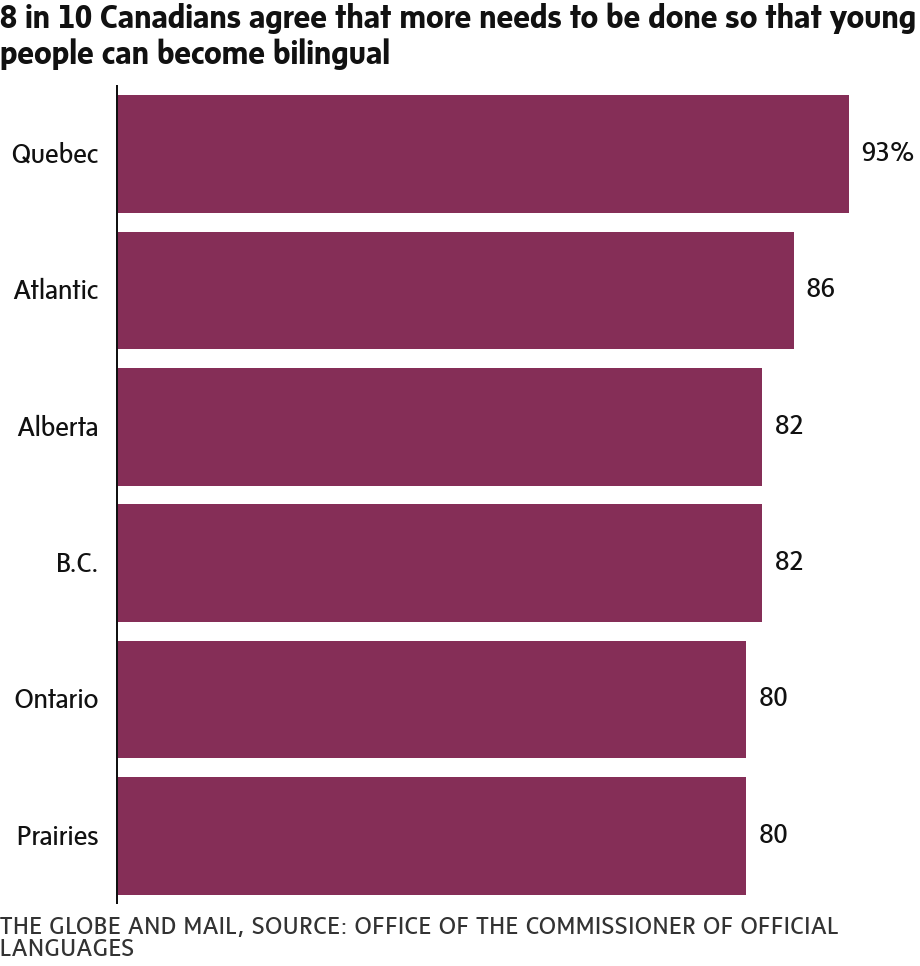

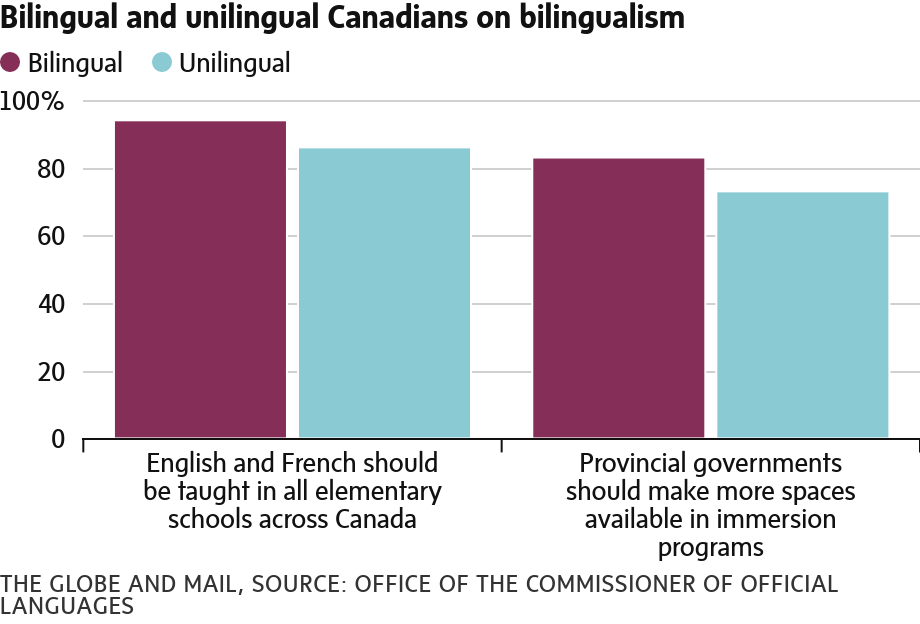

“More than ever, Canadians want their children to have access to the advantages that come with being bilingual, yet at the same time, there is a chronic and critical shortage of FSL teachers,” he said, adding students should not be denied an opportunity to become bilingual.

French is taught in a variety of ways in school, including French immersion and core French, in which students learn the language as a subject.

Jeremy Ghio, a spokesman for Mélanie Joly, Minister of Official Languages, said the issue of a French-language teacher shortage has been raised with federal officials during consultations. The government, in its action plan to strengthen minority communities and promote bilingualism, has secured $62-million to help provinces, territories and organizations address this issue, Mr. Ghio said in an e-mail statement.

The Commissioner of Official Languages report included a literature review, telephone interviews with provincial and territorial ministries of education and school boards across the country. It also involved interviews with French-as-a-second language teacher candidates and an online survey of teacher candidates.

Glyn Lewis, executive director for the Canadian Parents for French for B.C. & Yukon, said the report adds more evidence to what has become a critical issue.

In some B.C. school districts, parents have lined up outside school doors to ensure their children could get a spot in the French immersion program.

And in Ontario, where demand is high, school boards have reported difficulty in addressing demand because of teacher-shortage issues. Some boards have put a lottery system in place to contain the exploding growth.

Mr. Lewis said the report’s call for a standardization of French-as-a-second-language teacher qualifications would be unlikely across the country because education is a provincial issue. But perhaps provincial governments would consider this, he said. Some school boards, meanwhile, have recently started implementing a standard minimum requirement, while others use in-house proficiency tests when hiring new teachers.

“There’s an interesting conversation to have on how we create a benchmark for those standards,” Mr. Lewis said. But he said a teacher shortage changes the dynamics. “When push comes to shove, they [school districts] sometimes need to bend on those standards.”

EDUCATION REPORTER

The Globe and Mail, February 13, 2019