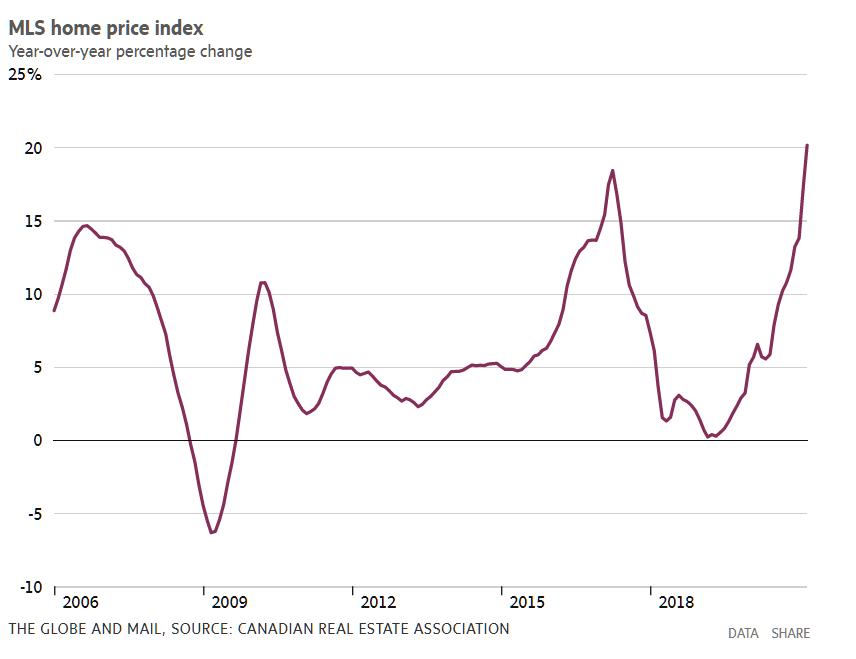

The rapid acceleration in housing prices is causing tremendous stress to the personal finances of individual households and the nation as a whole.

If it’s not vaccinations dominating conversations these days, it’s housing.

The national average selling price for existing homes last month was about 32 per cent higher than in March, 2020, and owners in communities across the country are feeling the benefits. Average prices in Chilliwack, B.C., Bancroft, Ont., and Yarmouth, N.S., were at least $100,000 higher than a year earlier, right in line with big cities such as Vancouver.

By handing owners these lottery-like gains in equity, the housing market has validated the almost religious belief of Canadians that owning a house is the foundation of financial success. But housing is also ripping the financial fabric of life apart in ways people are only just starting to talk about.

Young adults increasingly feel shut out of home ownership in big cities, even as their parents can’t stop talking about how much money they’ve made as owners. An exodus of buyers to smaller communities is pricing out local residents. People who can afford to buy are forced to make rushed, high-stress decisions about the biggest financial transactions in their lives, and then to take on debt loads that could limit their ability to save for retirement and deliver the spending the economy needs to recover from the pandemic. A whole new parental financial burden has been invented: making sure your adult kids get into the housing market.

The number of people who want to buy has swamped sellers, which in turn means houses in many locations sell in hours or days, buyers must bid against each other to land a home and offers have to be presented without the usual prudent conditions of arranging financing and having a home inspection. Call it a homebuyer’s hellscape.

If you own a house or are selling, you’re loving it. Who doesn’t feel smart owning a financial asset that jumps in price through a year of trauma and uncertainty? Who among us is not keeping track of what neighbouring houses are selling for and how that compares with our own purchase price?

The importance of real estate to Canadians can be seen in a home-ownership rate that is among the highest for industrialized countries at 67.8 per cent, according to a 2019 RBC Economics report. But house prices are rising to unaffordable levels for many in the next generation of buyers.

The average detached house price in Toronto and Vancouver in March was well above $1-million, the threshold where the minimum down payment is 20 per cent, or $200,000 (homes priced below $1-million can be purchased with a smaller down payment). A recent Royal Bank of Canada poll found that people who are saving for a home in the next two years are putting away an average $789 a month. At that rate, it would take 253.5 months (more than 21 years) to get to $200,000 without parental help. No wonder the poll found that 36 per cent of non-homeowners under the age of 40 have given up on the idea of purchasing a home.

Prices in smaller cities have risen enough to present affordability challenges of their own. Halifax is an example: The average resale price there jumped by $121,278 over the past year to $474,271. Joshua Elliott, a 25-year-old Halifax resident who works as an industrial piping designer, says he’s given up on the idea of swapping the two-bedroom rental apartment where his family lives for a house.

“My partner is a nurse who is working on COVID response and it would have been nice to have a place where she could go into the backyard to relax after a long shift,” Mr. Elliott said. “But with how the market is now, we can’t compete.”

Some young families are leaving cities in the pandemic for more spacious and affordable houses in the suburbs and locations well beyond. These buyers bring big city buying tactics with them, which means bidding over the asking price by enough to blow away competitors.

The result is that prices are soaring in communities where high house prices have never been a thing. Example: Kingston, where prices surged to $577,974 in March, up 36 per cent from the same month a year earlier.

Among those affected by this jump in the cost of housing is Kristen Darch, a 39-year-old who has been living with family in Ottawa while saving money to move back to Kingston with her 10-month-old daughter. She grew up in Kingston, and her mom and brothers live there. “Kingston always seemed to me to be the last bastion of sanity and accessibility,” she said. “Now, comfortable housing for a single-income family is a thing of the past. It’s so jarring.”

More distant cities such as Saint John, N.B., have also been affected by the migration of people from expensive southern Ontario real estate markets. The number of houses available for sale in Saint John in March was the lowest for that month in more than 20 years, while the average price jumped 39.6 per cent year over year to a record $265,095.

Decisions on whether to buy must be made in hours, in some cases, and buyers often have to bid blindly over the ask price to have a chance of getting a home. They must also forego the elementary precaution of having a home inspector go through a house to look for leaky basements, electrical problems, hack renovation work and more.

“People are making offers in the rush and mania of the moment,” said William Tatham, a Toronto real estate lawyer since 1974. “Their goal is to get an offer accepted because they’ve been turned down too many times before.”

Veteran Toronto mortgage broker Tuli Parubets had a couple as clients, both successful lawyers, who lost six or seven bidding wars before finally landing a home. Another client outbid the competition by offering $300,000 over asking, but lost out to another bidder who wrote a personal note appealing directly to the sellers.

“It’s a gong show,” Ms. Parubets said. “Tuesday nights, we drink a lot.” Note: Tuesday is a common night for making offers.

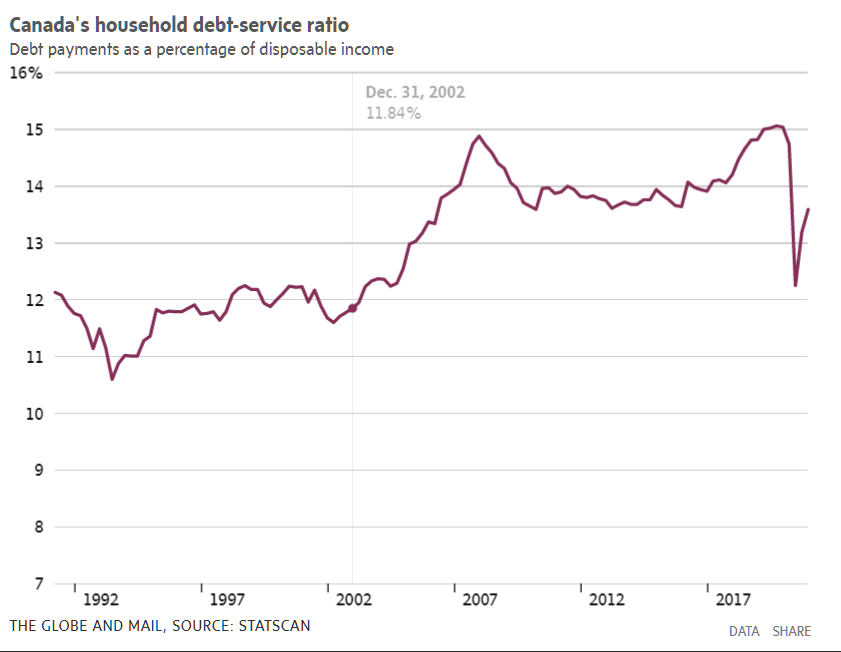

The stresses of buying houses in today’s market will be felt in the personal finances of both individual households and the nation. For a time, there was a credible argument to be made that the jump in house prices was financially manageable because interest rates were so low. But rates have edged higher this year and prices have surged. The burden on buyers is worse than ever.

Mortgage lenders have limits to the amount of total debt (mortgages plus student debt, car loans and such) that clients can take on in relation to income. But higher house prices mean buyers who qualify for a mortgage must come closer to their borrowing limits than they would have in a calmer market.

Devoting a larger share of a household budget to mortgage debt means less money available to pay other expenses. Pay increases might offer some relief, but the prospects for rising income will be uncertain in economic sectors that have struggled through the pandemic.

Less after-mortgage household income raises the potential for costly spending compromises. Saving for retirement or for a child’s postsecondary education might be sidelined and additional borrowing via home equity lines of credit might be used to pay for extras such as vacations and home upgrades. To support the economic recovery from the pandemic, we actually want households to spend in the years ahead on goods and services. In a world where only a minority of employers now offer pensions, retirement saving is also imperative.

When recent home buyers renew their mortgages in the years ahead, they should expect higher borrowing costs that leave them with larger monthly payments. A best case would be a return to the rates of late 2019 and early 2020, which were quite cheap in their own right. A more alarming and plausible outlook is for rates to move past those levels as government and central bank support for the economy in the pandemic ignites inflation.

Baby boomers have done especially well in the housing market and are eager for their adult children to experience similar financial success. Often, this means providing money that goes toward a down payment.

Helping adult kids buy a home has been part of parenting for generations. But today’s parents feel strongly enough about this to borrow against their own home equity. A recent report from Mortgage Professionals Canada says $2.8-billion was withdrawn last year from home equity lines of credit for the purpose of gifting or lending money to a family member to buy a house.

This amount is a relatively small slice of the estimated total $74.5-billion withdrawn from HELOCs in the past year, but still a financial burden worth noting at a time of concern about household debt levels in general. Interest rates on HELOCs can range from 2.45 per cent to 3.45 per cent and will start rising once the Bank of Canada starts pushing up borrowing costs in the years ahead.

The MPC report found that about 33 per cent of first-time buyers in 2020 got some form of financial assistance from family members. The national financial planning firm Money Coaches Canada says clients helping adult kids buy homes typically provide between $25,000 and $100,000.

“There are parents who will do whatever it takes for their children to buy a house, even at their own peril,” said Karin Mizgala, the Vancouver-based co-founder and CEO of Money Coaches Canada.

The rise of home prices in Canada is in some ways a benefit to the country. Housing-related activity has supported the economy in recent years and now accounts for about 14 per cent of total output, a level some critics feel is too high. The wealth effect, which makes people feel and act wealthier because of gains in the value of their home, has supported years of consumer spending that also feeds economic growth.

There’s also an undeniable morale benefit to housing’s rise in the past year. Because of a worldwide health catastrophe that at first threatened to destabilize the global financial system, houses steadily became more valuable. Our biggest financial commitment has become our biggest financial home run.

But the cost of the rise in housing prices is mounting, particularly for young adults who are being denied access to the what used to be the near-universal entitlement of home ownership. Governments and financial regulators have a choice to make: Introduce measures to contain price increases in the real estate market, or let housing keep tearing away at the financial fabric of Canadian life.

ROB CARRICK

PERSONAL FINANCE COLUMNIST

The Globe and Mail, April 28, 2021