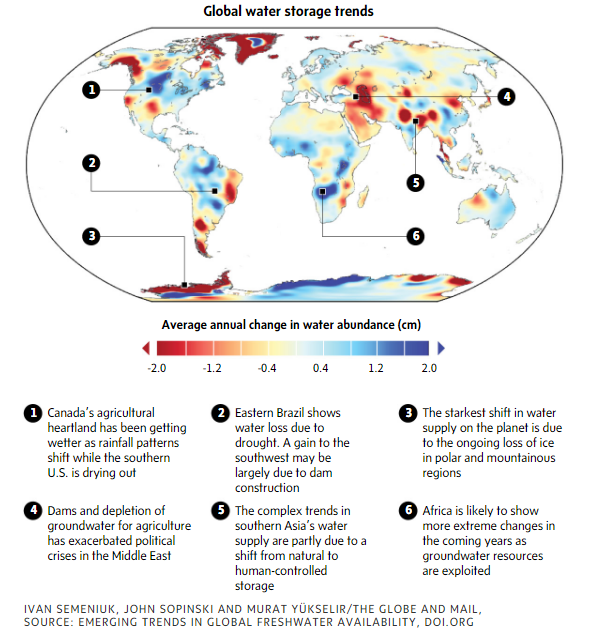

By combining 14 years’ worth of satellite data, scientists have captured a startling portrait of the world’s water supply undergoing rapid transformation. The new analysis points to areas where there is increasing potential for conflict as a growing demand for water collides with the impacts of climate change. In Canada, the maps shows shifting water supplies that include wetter, more flood-prone regions in many areas of the country but a general drying out in the western sub-Arctic.

“This is an eye-opener,” said Roy Brouwer, an economist and executive director of the University of Waterloo’s Water Institute who was not involved in the analysis. “It raises awareness that things are changing and that in some areas something has to happen to counter and anticipate some of the catastrophes that may be waiting for us in the not-so-far future.”

The analysis is based on data from the Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment, or GRACE, a NASA-led mission launched in 2002 that involved two satellites circling the globe in tandem about 220 kilometres apart. A microwave link between the two satellites allowed scientists to precisely monitor minuscule changes in their separation down to a distance of 10 microns, or about one-tenth the width of a human hair.

The setup created a sort of flying weight scale that mean the satellites could be used to measure slight regional variations in Earth’s gravitational pull. Many of those variations are due to geological features, such as mountain ranges, that do not vary over time. But by taking measurements over many years, the satellite also picked up changes that are largely due to the movement of massive amounts of water at or near Earth’s surface.

Researchers have published many results based on GRACE data but the new analysis, published Wednesday in the journal Nature, marks the first time all available observations from the mission, from April, 2002, to March, 2016, have been analyzed and assembled to provide a comprehensive map of water trends around the world. Those trends encompass changes in where water is stored across Earth’s surface, including groundwater, soil moisture, glaciers, snow cover and surface water. The result suggests a water landscape that is changing fast on a global scale, in large part due to human activity and climate change.

“The human fingerprint is all over what we see in the map,” said Jay Famiglietti, a water-resource expert affiliated with NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., and the incoming director of the University of Saskatchewan’s Global Institute for Water Security.

Dr. Famiglietti, a co-author on the Nature study, has played a central role in interpreting data from the GRACE mission over its lifetime. He added that the new analysis pointed to profound changes in the Earth’s water resources that should serve as a wake-up call for policy makers.

“There are implications in that map for food security, for water security and for human security in terms of things like conflict and climate refugees,” he said.

In total, Dr. Famiglietti and his colleagues identified 34 regional trends in water storage observed by GRACE. Some are likely due to natural variations over the time that the observations were taken. For example, the Amazon basin looks like it’s getting wetter because the area has been recovering from a drought. The same is likely the case for a region centred on the Canadian Prairies and parts of the United States. Over the long term, those trends may fade away.

The most obvious changes are clearly due to climate change and relate to ice loss in the polar regions and in some mountainous areas such as Alaska and the southern portions of the Andes in South America. Others show places where humans have directly affected water storage.

Similar shortfalls in India reflect the impact of subsidized electricity, which has created a “perverse incentive” that makes it inexpensive to pump out more groundwater than can be replenished, said Dr. Brouwer.

Overall, the map shows how the world’s water is increasingly moving from natural storehouses such as glaciers to human-built reservoirs, a change that comes with plenty of political fallout when that water crosses international boundaries, said Aaron Wolf, an expert in water-related conflict at Oregon State University.

“This kind of data really helps us identify hot spots in advance of real crises,” he said.

Support for the GRACE mission officially ended last fall and the last of the satellites burned up as its orbit decayed in mid-March. A follow-up mission with two new satellites that will continue the gravity measurements is currently set for launch this Tuesday from Vandenberg Air Force Base in California.

IVAN SEMENIUK

SCIENCE REPORTER

The Globe and Mail, May 16, 2018