When Erich Isopp was a child, one of the neighbourhood fathers would flood a rink in the park across the street of his Toronto home, and he and his friends would play ice hockey until the lights went out.

“I loved it,” says Mr. Isopp, 35, noting he played for fun, as well as for the exercise and camaraderie. “It was just something everyone did.”

But Mr. Isopp is reluctant to introduce his two-year-old son, Otis, to the sport. He’s learned too much about the dangers of concussions and chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), a neurodegenerative disease associated with repeated brain injury. He can list numerous professional players, such as brothers Brett and Eric Lindros, and superstar Sidney Crosby, who have been affected by concussions. Some have had their careers, and even lives, cut short.

“You really don’t want to mess with your kid’s head,” Mr. Isopp says.

In response to a growing body of research showing the long-term effects of concussion, hockey organizers have introduced rule changes, return-to-play policies and concussion-education programs in an effort to help prevent the brain injury and make sure it doesn’t go untreated. Meanwhile, sporting-equipment companies are tinkering with helmet designs and new protective gear, and researchers are trying experimental methods of testing for concussions – from genetic tests to identify who’s most at risk, to blood tests and apps for diagnosing concussions.

Yet in spite of these recent advancements, parents such as Mr. Isopp are asking fundamental questions that scientists, too, continue to grapple with: Just how dangerous is youth hockey? And what can be done to ensure young players play safely?

To arm parents with the best information available, The Globe and Mail sought out experts at the forefront of concussion prevention, research and treatment to provide a primer for Canadian families gearing up for a new season.

In response to concussion research, Hockey Canada in 2013 eliminated bodychecking at the peewee level, in which players are typically 11 or 12 years old. PETER POWER/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

How often do concussions occur in hockey?

It’s hard to know for sure. As Todd Jackson, director of insurance and risk management at Hockey Canada, explains, the governing body doesn’t collect data on every concussion that happens. Often, concussions occur and are taken care of at a local level, he says, so the national organization isn’t always made aware of them. “I really don’t have solid data that I can give you that says, ‘This tells you the picture,'” he says.

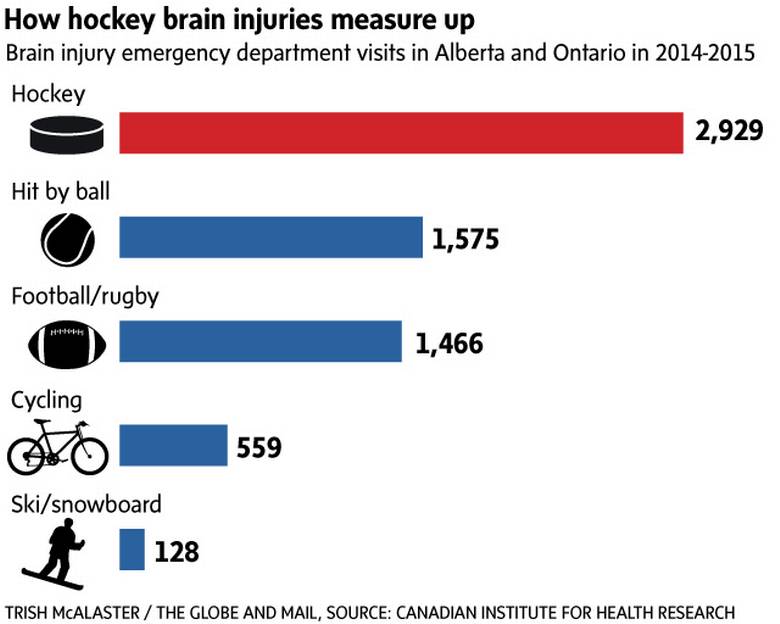

Yet, some emergency-room data suggest concussions may be particularly prevalent in hockey. In Ontario and Alberta, the number of emergency-department visits for brain injuries from hockey was almost double that from cycling, football and rugby, and skiing and snowboarding in 2014-15, according to the Canadian Institute for Health Information.

Data from the Institute show the number of hockey-related brain injuries that required emergency-department visits in those two provinces edged up slightly to 3,008 in 2015-16, from 2,929 in the previous year. The greatest number of those injuries occurred among children ages 10 to 14.

How do young hockey players get concussions?

In 2012, the Canadian Paediatric Society published a position statement calling for the elimination of bodychecking in non-elite youth ice hockey. The statement, co-authored by Carolyn Emery, who is currently chair of the Sport Injury Prevention Research Centre and associate dean of research for the faculty of kinesiology at the University of Calgary, noted that studies had consistently identified bodychecking as the primary cause of hockey-related injuries, including concussion.

In response to the work of Dr. Emery and other concussion researchers, Hockey Canada in 2013 eliminated bodychecking at the peewee level, in which players are typically 11 or 12 years old. Other local governing bodies have delayed the introduction of bodychecking til players are even older. For example, Hockey Edmonton last year decided to disallow body checking for most players up to age 17, unless they play at a more competitive level.

This appears to have dramatically reduced the risk of concussion for young players. A study published earlier this year in the British Journal of Sports Medicine, co-authored by Dr. Emery, found a 64-per-cent reduction in the concussion rate of peewee-level hockey players in Alberta after the policy change. (The incidence dropped to 1.12 concussions per 1,000 game hours, down from 2.79 per 1,000 game hours prior to the rule change.)

Dr. Emery is currently engaged in a study that follows 1,000 young players annually over a five-year period, as they’ve moved to higher levels of play and have undergone various local rule changes on bodychecking to try to seek some answers to lingering questions, including at what age and level of play should players begin bodychecking in games.

But even without bodychecking, there’s still plenty of contact in youth hockey. And simply falling on one’s back, for instance, can cause the brain to move around in the skull.

How many concussions are too many?

“My answer to that is it’s very individual, and everyone is very different,” says Nick Reed, co-director of the concussion centre at Toronto’s Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital.

Dr. Reed says the seriousness of an injury can depend on a number of factors, including how much time has passed between repeated concussions, whether players are being concussed again with less force over time and how much the injury affects their daily lives. For instance, how is the concussion affecting one’s ability to function at school or to spend time with friends?

If repeated concussions are increasingly taking a toll on daily life, “then it’s time to start thinking about the pros and cons of putting yourself at risk of even more severe impact on life down the road,” Dr. Reed says.

The bottom line is every concussion should be treated seriously, Dr. Reed says.

Why are concussions often difficult to detect?

The trouble with concussions is there is currently no scan, tool or blood test that’s been supported with enough evidence to accurately and reliably detect them, Dr. Reed says. (He notes the science of concussions, particularly pediatric concussions, is still young. There’s a lot more research that needs to be done to understand them, as well as to understand subconcussions, which are repeated impacts to the head that may not directly result in signs and symptoms, but may, over the course of seasons or years, affect the brain.)

In the absence of validated tools and scans, clinicians must rely on players to tell them how they’re feeling, he says. Common symptoms include headaches, dizziness, nausea, increased anxiety or feeling like you’re in a fog or simply not quite yourself. But players may not experience symptoms right away.

Clinicians also rely on other people, including coaches, parents and teammates, to report signs such as whether the player looked wobbly on the ice, whether they had to lie down for a while after taking a hit or whether they seemed out of sorts. Recognizing concussions is a team effort, Dr. Reed says.

While many hockey teams have now introduced baseline testing, an exam typically given at the start of the season to provide a comparison of a player’s performance if he or she is injured, Dr. Reed says researchers still need to determine if baseline testing is reliable and sensitive enough to detect cognitive deficits. It does, however, offer a good opportunity for health professionals to engage players early in the season and educate them about concussions and about what to do if they experience them, he says.

What is the best treatment for concussions?

A critical part of treatment involves seeing a medical professional, who can determine whether players have sustained a concussion or a more serious brain injury, Dr. Reed says. If they do have a concussion, players need to get plenty of sleep and rest, ensure they stay hydrated and eat healthful food during the first 24 to 48 hours, he says.

Forget what you’ve heard about the need to frequently wake a concussed child.

Children need to sleep when they’ve had a concussion, though parents will likely get less shut-eye so they can monitor their child’s breathing and make sure he or she isn’t struggling, Dr. Reed says.

After the initial 48 hours, school and social activities may be gradually introduced, as long as players’ symptoms don’t get much worse. Once they can handle school and general life activities without their symptoms returning, they can begin to return to their sport. However, Dr. Reed says it’s important to see a physician before they start playing games again.

What kind of gear will protect my child?

Helmets can protect against some injuries, such as skull fractures. But so far, there hasn’t been any equipment that’s been proven to reduce risk of concussion.

Dr. Emery and her team are currently evaluating the impact of helmet fit on concussion risk. And although she says there is some evidence to suggest the use of mouthguards could be protective against concussion, the mechanism of this protective effect is not well understood.

Sporting-equipment companies, however, continue to design new products in attempt to improve player safety, such as Bauer’s NeuroShield, a collar introduced this year that’s worn around the neck to increase blood volume around the brain. While the company explicitly states it does not prevent concussion, it says it helps protect the structure of the brain.

But until they see more research on the efficacy of these products, the best advice experts give for preventing injury is to play the game safely.

What does safe hockey entail?

Part of playing safely is following the rules of the game, which includes zero tolerance from Hockey Canada for checks from behind and hits to the head, says Paul Carson, vice-president of membership development at Hockey Canada. Practising and developing skills, such as skating with agility and confidence and keeping one’s head up while carrying the puck, is also important, he adds. And critically, he emphasizes the need to foster a respectful environment, which involves everyone from parents, coaches and trainers to players themselves.

“We still see in arenas all around this country big loud cheers for the big hits rather than for the nice pass or the nice goal,” Dr. Reed adds. But “if we can start to have young kids respect their own brains and the brains of others, I think we can make some significant headway.”

1. What’s your philosophy around play?

Is it all about winning? Or ensuring players enjoy themselves?

Parents should get a sense of the culture the coach will set for the team, and find out about the coach’s views on violence in the game, says neurosurgeon Michael Cusimano, director of the injury prevention unit at St. Michael’s Hospital in Toronto.

The same goes for the league, he says: Does it have “fair play” rules, where a team may lose points if it has too many penalties? Are bodychecking and fighting allowed?

Asking about the culture is “critically important because I think those kinds of things define the rate of injury that you’re going to see – and not just with concussion, but with all forms of injury,” he says.

2. What are the penalties for dangers play?

If a player hits someone in the head, what will happen to that player? Will the coach be penalized?

“If there’s a coach who’s encouraging … play that risks injury to other players, I think the coach has to be taken to task there,” Dr. Cusimano says. Parents need to encourage repercussions for unsafe coaching and to talk about it among themselves, he says, because “sometimes it’s other parents who are giving peer pressure to the coach.”

3. What is your team doing to educate players about concussions?

The majority of concussions are diagnosed because an athlete has come forward with a specific complaint, such as nausea or dizziness, says Scott Delaney, associate professor and research director in the department of emergency medicine at McGill University Health Centre.

But players will not likely do that unless they know the signs and symptoms, and understand the risks, Dr. Delaney says, noting that older athletes, in particular, may try to shrug off symptoms. “You have to make them aware … so they understand, ‘This is not safe. I need to go tell somebody,'” he says.

4. What happens if my child has signs or symptoms?

A coach should not be made responsible for determining whether a player is well enough to play. If there is any suspicion a child has a concussion, he or she should immediately be removed from play and taken for medical evaluation.

“There’s an expression … we use in concussions: ‘When in doubt, sit them out,'” Dr. Delaney says.

5. Is everyone on the same page?

Dr. Delaney recommends that teams use a concussion contract, such as one created by McGill Sport Medicine Clinic and Montreal Children’s Hospital. Not legal contracts, these are agreements among parents, coaches and players so that everyone understands what to look for and the protocol for handling suspected concussions.

Players agree to inform the coach and parents if they have any signs or symptoms. Parents agree to notify the coach and to seek a medical evaluation for their child before he or she returns to play. And coaches agree to take the child out of play if a concussion is suspected, and to inform the parents.

The Globe and Mail, October 15, 2017