For anyone younger than 20 – in other words, those who have lived entirely in this century – climate change is a fact of life that has fast become a matter of collective urgency.

This cohort is set to witness in the years to come some of the most significant effects of climate change thanks to the greenhouse gasses that have been released into the atmosphere since the start of the Industrial Revolution. Some effects are already deemed inevitable.

It is also the cohort that will find out, first hand, whether society can be nimble enough to change course and avert something more severe in the century beyond.

“If you choose to fail us, I say: We will never forgive you,” 16-year-old activist Greta Thunberg told delegates at the United Nations Climate Action Summit in New York this week.

Ms. Thunberg’s appeal for action has struck a chord, in part because it is bolstered by what people already see happening around them. In Canada, that includes heat waves, severe floods and widespread smoke from forest fires, all of which can be attributed at least in part to climate change.

Each year, scientists accumulate more data on the planet’s response to ever-higher concentrations of heat-trapping gasses from fossil fuels. These data add confidence to models that project where things are heading. They also show that the human-caused change is getting easier to distinguish from the natural variability of the climate.

Adam Fenech, director of the University of Prince Edward Island’s Climate Research Lab, said trends he and colleagues once envisioned decades ago, such as rapid ice-shelf breakup in Antarctica and category-five hurricanes making landfall in North America, are coming to pass.

“We’ve always said that this is the direction things would go, but now the reality is hitting home,” Dr. Fenech said.

“It means we have a choice to make,” said Xeuben Zheng, a senior research scientist with Environment and Climate Change Canada, and one of the lead authors of a federal report released last spring on the anticipated effects of climate change across the country.

One choice, Dr. Zheng said, is to make changes in the near term to help mitigate some of the more serious effects coming later this century. The other is to face the cost and upheaval of adapting to a very different world. One way or another, Dr. Zheng added, “there’s no easy escape.”

On Friday, student-led climate strikes offer another sign that a national discussion on climate change is under way, prompted by those who will be most affect by policies pursued in the next decade. Here is a summary of what we know today about some of the future climate effects young Canadians are likely to face.

WEATHER EXTREMES

Regardless of what choices are made, one aspect of the future can be stated with virtual certainty.

“Canada is getting hotter,” said Dr. Zheng, whose specialty is the statistical analysis of climate trends.

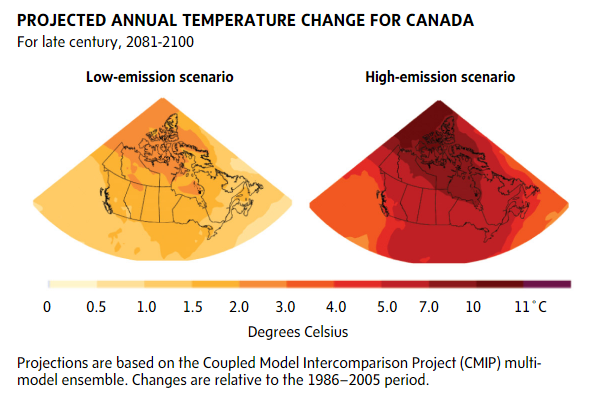

Exactly how much hotter depends on which path the world takes to reduce carbon emissions. But Canada will warm at about twice the global average and the Arctic will warm at three times that rate. Severe heat will be a growing problem in cities that are not used to it. Under a high-emissions scenario, the average number of days above 30 degrees in Montreal, which experienced 66 heat-related deaths last year, will increase five-fold by 2080.

More heat also means the air can hold more moisture. That sets up conditions for severe downpours and flash floods. Trends for seasonal flooding are harder to forecast because they depend on additional factors, including diminishing winter snowfall and the rate of spring melting. And while Canada may experience more rain overall under climate change, the summer months stand to be hotter and drier in the west, creating the conditions for more severe forest fires such as Fort McMurray, Alta., experienced in 2016.

ARCTIC MELTING

The warming of the Arctic stands apart because its impact on communities and ecosystems is being felt sooner and more profoundly than in the south. In addition to higher temperatures – including a record-breaking 21 degrees in July at the Canadian Forces Station Alert – ice loss across the region is causing fundamental changes on land and sea.

Summer sea ice extent across the Arctic Ocean is on a steady downward trend, producing more ice floes and exposing coastal communities to higher rates of erosion. This effect introduces a crucial feedback loop, because ice serves as a counterbalance to warming by reflecting sunlight away from the planet.

Permafrost – the permanently frozen soil that covers approximately one quarter of the country’s land area – is also in retreat, a costly threat to northern infrastructure such as roads, buildings and airports.

Because permafrost locks up a vast reservoir of soil carbon, its disappearance could contribute to more severe levels of global warming if emissions are not reduced in time. Such scenarios are difficult to model, but Merritt Turetsky, an Arctic ecologist at the University of Guelph, sees little reason in her data to be complacent.

“All I can say is, our eyes need to be trained on the North, because that’s what’s coming for us next,“ Dr. Turetsky said.

SEA-LEVEL RISE

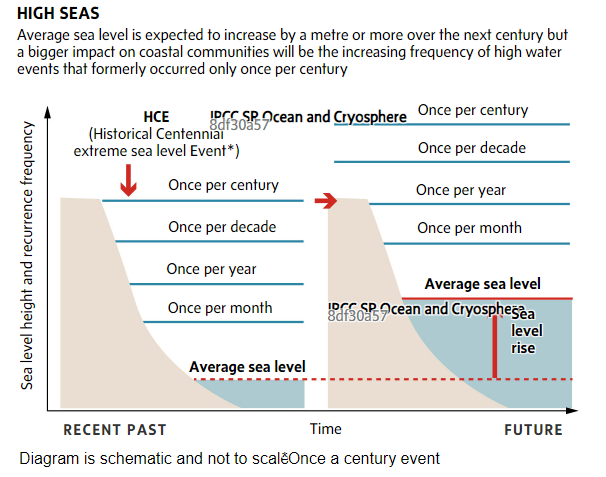

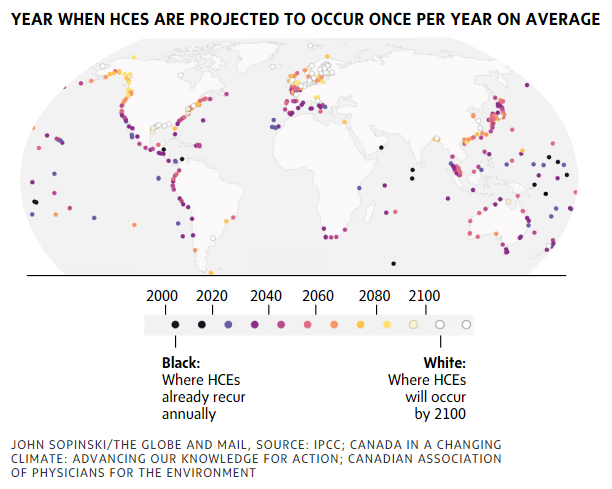

Slowly but surely, the global average sea level is inching upward, driven by expansion due to warmer water and by the melting of ice sheets in Greenland and Antarctica.

“These processes take time to evolve … and they’re gaining momentum,” said Glenn Milne, a geophysicist with the University of Ottawa. “Even if we were to cut emissions today, we’re already committed to a certain amount of sea-level rise.”

In some places, that is exacerbated by other factors. For example, land is sinking along Canada’s east coast as central Canada rebounds after the glaciers receded at the end of the last ice age.

Dr. Milne and his colleagues have calculated that this effect will add nearly 20 centimetres to a sea-level rise of 30 centimetres expected by the end of century. While that may not seem like much in a part of the world where the tide is measured in metres, what matters more is the frequency of storm-driven high-water, which threatens lives and infrastructure. As the average sea level rises, these high water events that were formerly seen once per century will eventually come yearly.

HEALTH EFFECTS

Human health is an area where the impact of climate change is increasingly gaining recognition.

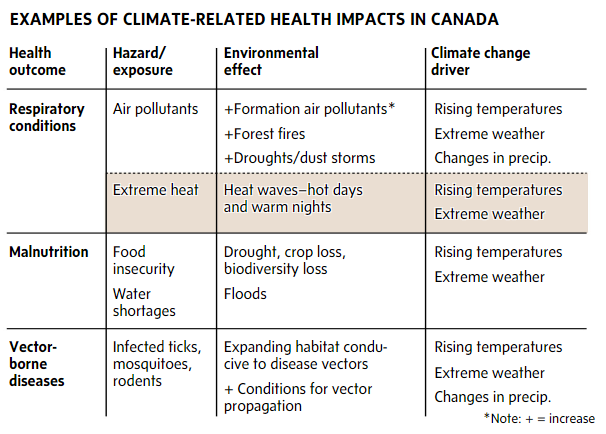

In Canada, documented effects include physical injuries and mental stress related to severe weather disasters, emergency evacuations and displacement from homes. They also include long-term and chronic problems from poor air quality, longer allergy seasons, and heat and humidity.

Warmer weather also creates a gateway for pathogens – a fact that is evident from the rising number of cases of Lyme disease, which increased five-fold in Ontario between 2012 and 2017. As the warming continues, diseases more commonly associated with the tropics, such as dengue fever, are likely to follow.

For Courtney Howard, an emergency room doctor in Yellowknife and board president of the Canadian Association of Physicians for the Environment, it is these kinds of effects that are most likely to force policy-makers to action.

“More and more Canadians are experiencing climate change in their own bodies, and it’s starting to feel real to them,” Dr. Howard said.

IVAN SEMENIUK

SCIENCE REPORTER

The Globe and Mail, September 26, 2019