Policy makers say higher immigration is necessary to fuel Canada’s economic growth, and in particular, to ease labour shortages, but with a population boom comes growing pains.

Every year, Canada adds a big city – in a sense. The mass of individuals are spread around, mostly to urban centres, but increasingly to suburbs and far-flung communities. They are here to work, to study, to build a better life.

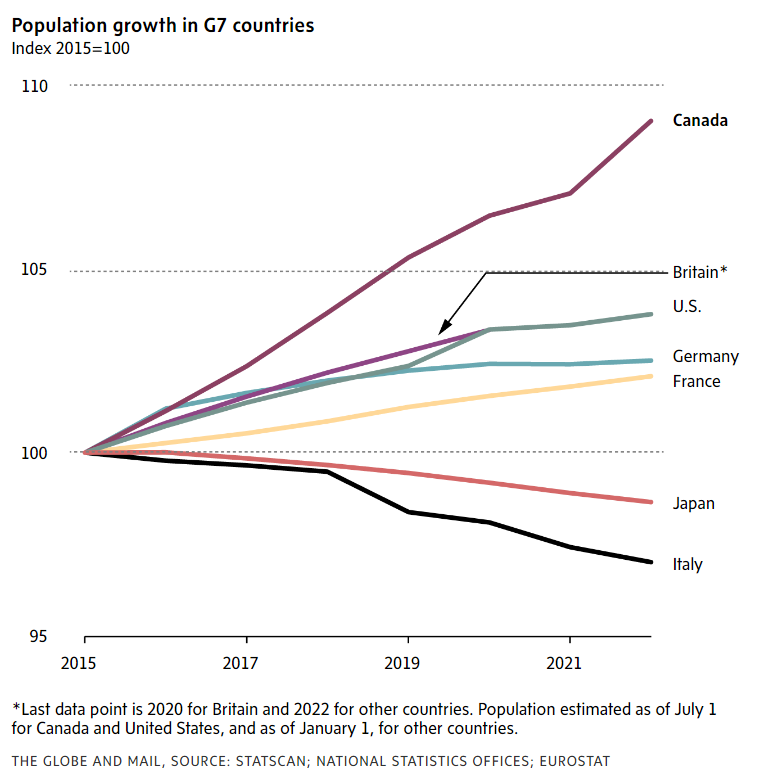

The expansion is historic. From July to September, Canada’s population grew by around 285,000, a 0.7-per-cent gain that was the largest since Newfoundland joined Confederation in 1949. More than 700,000 people have been added over the past year, roughly the same as the population of Mississauga, the seventh-largest municipality in the country.

The trend picked up when the federal Liberal Party came to power. Since 2016, the country has grown at nearly double the rate of its Group of Seven peers. For the most part, that growth is driven by immigration.

The push is deliberate. Policy makers say higher immigration is necessary to fuel Canada’s economic growth, and in particular, to ease labour shortages that have frustrated the corporate sector.

It is, however, a population boom with its share of growing pains.

Consider that over the past year, around 220,000 housing units were completed. There were 3.2 new residents for every home added, the highest ratio since at least 1991. Affordability is deteriorating in most places. There is a fundamental mismatch between home supply and demand – and the population boom is contributing to the divide.

At the same time, Canadian governments are struggling to deliver basic services. Surgeries are getting cancelled in crammed hospitals. Canadians can’t find family doctors, let alone newcomers trying to navigate an ailing health care system. Cash-strapped cities can’t refurbish their infrastructure as fast as it’s falling into disrepair.

To cope with the affordability crisis, a growing number of people are fleeing our cities. They include teachers, nurses and construction workers – the very people who keep those cities running.

In this fraught environment, Ottawa has its foot on the accelerator. After admitting about 405,000 permanent residents last year, the federal government is aiming for 500,000 in 2025. And that’s just a portion of the migration wave: At last count, there were 1.4 million residents with temporary work or study permits.

Canada is facing a complicated adjustment. Notably, developers are scrapping or delaying housing projects, owing to rising interest rates and waning profitability. Just when more homes are needed, fewer are being built.

Several economists question why the federal government would create more demand for services, when so many pillars of social infrastructure are in distress. They wonder if Ottawa is singularly focused on hitting its immigration targets, with insufficient planning for how to successfully absorb those newcomers.

For its part, the federal government says the solution to so many of these problems is simple: more immigration. They’re planning to bring in more doctors and nurses from abroad, along with people to build homes.

Many recent immigrants have waited years for admission. Now they’re arriving at a time of decades-high inflation and slowing economic growth. Highly-skilled newcomers will likely manage the transition just fine. But others are discovering the Canadian dream is a pricey proposition – and perhaps not what they bargained for.

Ash Gopalani knew Toronto would be expensive. Just not this expensive.

He and his wife, Sneha, arrived in September, after a stressful three-year process to get their permanent resident cards. Finding an apartment was the next hurdle. Too often, the listings were in cramped basements, with little natural light, or far removed from the city’s core or public transit.

Mr. Gopalani eventually signed a lease for a one-bedroom unit in the city’s west end for $1,800 a month, the top end of his expected range. What he didn’t anticipate was paying six months of rent – $10,800 – up front, because the couple from Mumbai has no credit history here. Now, they have less of a financial buffer as they search for jobs.

Mr. Gopalani was hoping to follow a familiar playbook for newcomers. Establish a career. Save up money. Then buy a house – preferably big enough that their family from India could stay a while.

But the experience of moving here has been a reality check.

“We don’t know if we can afford building a life in Canada,” he said.

The rental market is ground zero for where immigrants get a taste of the cost-of-living crisis, in which fierce competition and bidding wars for relatively few units have led to jacked-up prices.

For Alexiane Sauvaire, it was a rude awakening. She thought finding an apartment in Toronto would be easier than in her native Paris. After eight frustrating days of looking, following her arrival, she moved to Montreal.

“Maybe for rich people, it’s easy. But when you’re not rich, it’s impossible to live right now in Toronto,” she said.

Increasingly, recent immigrants are bypassing the largest metro areas – Toronto, Vancouver and Montreal – to settle elsewhere, although a slim majority still favour those regions, according to the latest census results. However, costs are rising quickly in other cities, too, as they experience fervent demand from migrating people.

Over the past year, the average rent in Calgary has jumped 18 per cent to around $1,720 a month, according to data for new listings on Rentals.ca. London, Ont., is up 26 per cent. Halifax: 21 per cent.

From a labour standpoint, the affordability crisis is making it difficult to recruit – and retain – important workers.

“There are very significant economic risks to large cities if they do not get housing costs under control,” Aled ab Iorwerth, deputy chief economist at the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corp., said on a conference call this summer. “It’s getting increasingly difficult to attract skilled workers and even highly-skilled workers to these cities because they’re just becoming simply unaffordable.”

The task ahead is nothing short of gargantuan. CMHC says that, in order to restore affordability back to levels in 2003 and 2004, Canada would need to build 3.5 million more homes than projected by 2030.

Earlier this year, the federal government unveiled billions in new spending for housing, with a goal of doubling construction over the next decade. That plan looks dead on arrival amid higher borrowing rates.

There is, of course, another problem: labour. In a recent report, CMHC said there were not enough skilled workers to build the homes so desperately needed.

“Even under more ideal conditions, I don’t think we have the capacity to build at a pace that matches the demand through population growth that we’re seeing,” said Shaun Hildebrand, president at real estate firm Urbanation.

Immigration lawyers have a blunt message: The application system is a mess.

And it’s a mess that was largely created in Ottawa.

Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (the federal immigration department) had around 2.2 million applications in its inventories as of Oct. 31. About 1.2 million of them were in backlog, meaning they’ve been in the system for longer than service standards for processing. That’s far higher than before the COVID-19 pandemic.

“The system is falling apart. I’ve never seen it like this, in the 20 years that I’ve been practising,” said Kerry Molitor, an immigration consultant in Toronto.

After failing to hit immigration targets in 2020, owing to pandemic challenges, the federal government wanted a rebound. Through various decisions, it invited thousands of people already in Canada to apply for permanent residency. The surge in applications overwhelmed a civil service that struggled to process files efficiently amid office closings and the shift to remote work.

In some cases, applicants are waiting years for a decision. Mr. Gopalani and his wife applied for permanent residency in the fall of 2019. They expected an approval within months, a typical outcome in their stream of immigration. They weren’t approved until July, 2022.

“The immigration system could have been more sensitive, empathetic, towards the kind of transition that people go through, which didn’t happen,” he said.

Because of the backlog, applicants such as Mr. Gopalani have put their lives on hold for years. Others are working in Canada, but their permits are nearing expiry, putting their future plans in doubt. These are individuals who, in Canada’s points-based system for economic immigrants, would often be shoo-ins for approval, but now are caught up in a bureaucratic nightmare.

There are “really good, quality people in the pool, and they’re not getting invitations,” said Mikal Skuterud, an economics professor at the University of Waterloo. “What happens now when these folks leave? They say, ‘The hell with this, I’m going back to my country or the U.S. or wherever.’ Now you’re losing all that talent. That’s completely not what this process is supposed to be.”

Despite the administrative headaches, Canada is on pace to welcome 431,000 permanent residents this year, right on target. The trouble is that talented people are slipping through the cracks – and the immigration system is taking a beating in public opinion.

“There’s this massive psychological toll that the backlogs, the delays and the lack of transparency have on people,” said Lev Abramovich, an immigration lawyer in Toronto. “I don’t think IRCC bureaucrats and politicians understand how much suffering this has caused.”

For all of Ottawa’s talk of targeting the best and brightest, the federal government is also allowing more cheap foreign labour into the country. Earlier this year, it overhauled the Temporary Foreign Worker (TFW) program, largely so employers could access more low-wage labour.

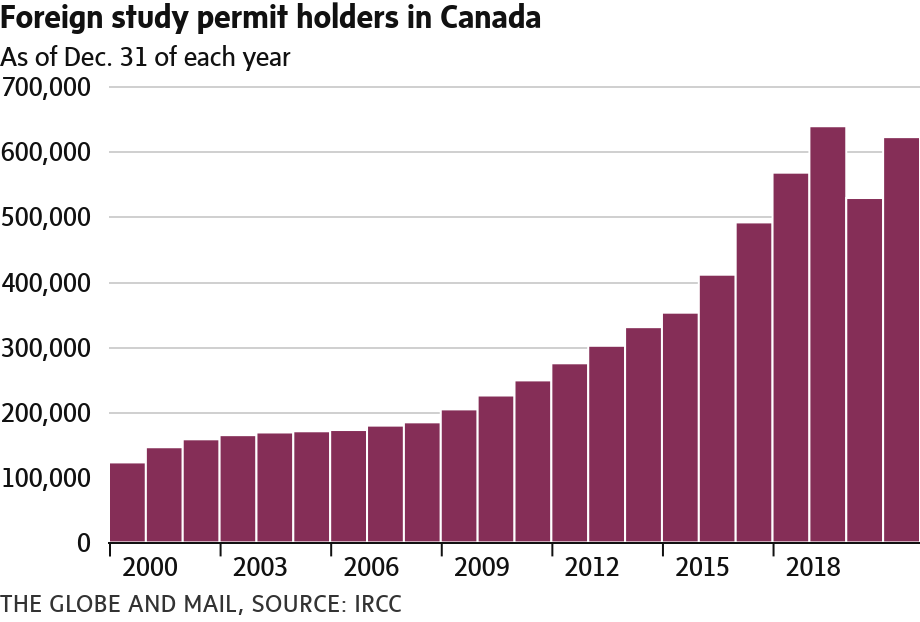

Colleges and universities, meanwhile, are ramping up their intake of foreign students, who mostly don’t need work permits. Increasingly, those students are taking jobs to rack up points for their permanent residency applications.

Around 1.4 million people had temporary work or study permits at the end of 2021, an increase of 85 per cent since 2015. That’s 640,000 people – about equal to the city of Vancouver – who have been added in just six years. Their ranks are set to accelerate this year, after policy changes.

While Ottawa has targets for admissions of permanent residents, there are no such guidelines for other migrants. With students, the federal government has essentially ceded that responsibility to postsecondary institutions, which are inclined to boost their revenues through higher intake of foreign students, who pay lofty tuition fees.

“The number of foreign nationals who receive study permits in any given year is based on demand, not predetermined targets,” Rémi Larivière, a spokesperson for IRCC, said in a statement.

An extreme example: Cape Breton University. Nearly 4,000 of its full-time students this fall had study visas, up a whopping 68 per cent from last year, according to preliminary survey data from the Association of Atlantic Universities. About three-quarters of CBU’s full-time students are from abroad. That’s injecting a surge of new demand for services in sleepy Sydney, N.S. (population: 31,000).

Gurmeet Singh, a second-year student, is trying to help people with their transition. He’s part of a volunteer group that verifies rental listings for incoming students. On average, the group gets three requests daily to check out potential residences. Mr. Singh visits those listings to see if they’re suitable for living – and if they exist.

Fraudulent listings are fairly common, Mr. Singh said; the group finds a scam every couple of days. “We felt it was our moral duty to help our fellow international students,” he said.

That’s not the only source of frustration. In local media this week, CBU students complained that a majority of classes in the two-year postbaccalaureate business program – a popular choice among foreign students – were being held in an unexpected venue: a Cineplex Inc. movie theatre off campus.

Higher immigration is a guiding principle for this iteration of the federal Liberal Party.

Time and again, the party frames immigration as the antidote to an aging population, helping to grow the pool of labour market participants – and thus, too, the economy.

“Immigration is not just good for our economy, it’s essential. We can’t get by without it,” Immigration Minister Sean Fraser told reporters at a recent news conference.

The truth is more complicated. A vast body of economic literature shows that immigration has little effect on gross domestic product per capita, a popular measure of living standards. Furthermore, while new immigrants are younger than existing residents, the intake is too meagre to offset a demographic wave of aging citizens.

This doesn’t mean immigration is bad for the economy. But it’s not an accelerant, either.

“Often, the argument is made as if it’s obvious that immigration generates economic growth,” said David Green, an economics professor at the University of British Columbia. “Not if you look at the numbers.”

Of late, Ottawa has said various policy changes – including the expansion of the TFW program and allowing foreign postsecondary students to work longer hours – are aimed at easing labour shortages. This has led several economists to accuse the federal government of kowtowing to corporate pressure, flooding the job market with low-wage foreign labour, rather than forcing companies to hike wages or make investments.

“There’s lots of evidence that holding employers’ feet to the fire in times of tight labour markets is the best way to spur innovation, automation and productivity. Those are the things you want in an economy,” said Jim Stanford, director of the Centre for Future Work, a think tank.

“And if you say to employers, ‘Don’t worry, we’ll let you bring in some low-priced temporary migrants to solve your problem,’ you’re just dissipating the pressure that’s required to achieve a more productive economy.”

Prof. Green questioned the need to admit half a million permanent residents in 2025, given the fragile state of Canada’s social infrastructure and the questionable economic rationale for that target.

“I don’t see the planning here,” he said. “Do you really want to ramp up to 500,000 a year, at a time when we seem to be heading into recession and our housing markets and our health care system are straining at the seams? That’s a discussion that should be had.”

By and large, surveys suggest Canadians welcome immigrants. A recent poll, conducted by the Environics Institute for Survey Research, found nearly seven in 10 respondents support current levels of immigration, about double the share in late 1970s. The vast majority of respondents – 85 per cent – agreed that immigration is positive for the economy, a view that has held strong for decades.

But Prof. Green suggests we shouldn’t take that for granted. If the country struggles to integrate newcomers, then perhaps Canadians will start to eye them suspiciously. “It’s politically dangerous, to my mind,” he said.

For now, that’s a worry. But it’s not the experience of Tanushree Holker and Nishant Kalia, who moved to Toronto from New Delhi in the summer of 2019. Their expectation of Canada as a welcoming country has checked out.

“That perception about Canada being a country which accepts immigrants with open arms, it is true when you come here,” Ms. Holker said.

The couple has shared their journey in Canada on YouTube; their channel, In The North, has nearly 100,000 subscribers, to whom they dispense their acquired wisdom on everything from buying a car to navigating a complex immigration system. Mr. Kalia started the channel after getting laid off early in the pandemic. He’s since built a career in human resources, while his wife works for a Big Six bank.

In recent videos, they’ve documented a major life change: They moved to Calgary. By doing so, they’re saving $350 a month on a similar-sized rental unit, and they expect to buy a home within six to nine months. Despite any number of financial complications, their version of the Canadian dream is going to plan.

“After we made our trip to Alberta, we realized that there is actually a life in Canada beyond Toronto and Vancouver,” Mr. Kalia said in a video. “To our surprise, [Calgary] was much better than we expected.”

MATT LUNDY

ECONOMICS REPORTER

The Globe and Mail, November 26, 2022