The Canadian literary community is mourning the death of Alice Munro, winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2013 and the Man Booker International Prize in 2009.

A friend to many in the writing community, and beloved by countless readers of all ages, Ms. Munro died on Monday in a care home in Port Hope, Ont. She was 92 and had been living with dementia for a decade.

Her family, who confirmed her death to The Globe and Mail on Tuesday morning, has asked for privacy as they gather to mourn their mother and grandmother and to make funeral arrangements.

“We are all wordless,” Michael Ondaatje, himself the author of many prizewinning novels, including the Man Booker and the Giller Prize, wrote in a one sentence e-mail Tuesday, capturing the mood succinctly of both grieving readers and writers.

Margaret Atwood, herself no slouch when it comes to literary accolades, had a long-standing and often jokey relationship with Ms. Munro, which included shared anecdotes about fans mistaking one of them for the other.

In a brief interview about her friend, Ms. Atwood cheerily recounted incidents where she had been congratulated on winning the Nobel Prize, an award for which she is regularly nominated in her own right. On a more serious level, Ms. Atwood has shown her appreciation in several essays, including her introduction to Alice Munro’s Best: Selected Stories. Quite simply, Ms. Atwood asserted that “Alice Munro is among the major writers of English fiction of our time.”

As her long-time friend, novelist Jane Urquhart said in an interview: “Alice had a genuine gift for intimacy and friendship, especially because of her enthralling conversational skills.”

Ms. Urquhart said Ms. Munro “was so intensely interested in her fellow human beings. Understanding them was her life’s work.”

As a writer, Ms. Munro could pack more insight, nuance and suspense into a few pages than many others could cram into a novel. “She was one of the great writers of the short-story form in the world today,” said David Staines, a literature professor and the former general editor of the New Canadian Library who knew her for more than 40 years as a friend and colleague.

He said he had invited her to be on the jury of the inaugural Giller Prize, an award she would subsequently win twice during her lengthy career.

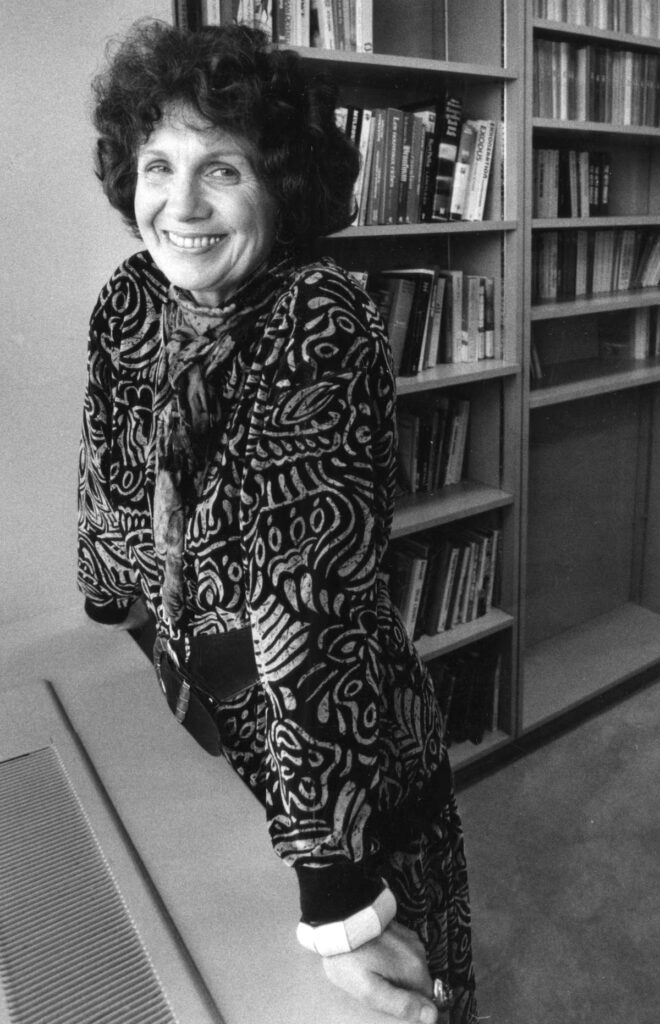

As a writer, Ms. Munro could pack more insight, nuance and suspense into a few pages than many others could cram into a novel. TIM MCKENNA/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

“In her life, she evidenced the beauty of the word,” Prof. Staines said in an interview. Asked how she compared with other short-story icons, such as Anton Chekhov and William Trevor, he said, “She will outlast her times, as they did theirs.”

Her death drew tributes from the political arena, too. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau called Ms. Munro a “true literary genius” whose gift for writing will be an inspiration for generations. “Alice Munro was one of the world’s greatest storytellers,” Mr. Trudeau said in a statement. “Her short stories about life, friendship, and human connection left an indelible mark on readers. A proud Canadian, she leaves behind a remarkable legacy.”

Miriam Toews, who has written seven bestselling novels, recalls a visit with Ms. Munro that shed light on her writing process. “Eight or nine years ago Rebecca Garrett, Alice’s goddaughter, and I were invited over to Alice Munro’s house for lunch. We brought Alice’s favourite things: Pinot Grigio, sushi and chocolate.”

Ms. Munro told them that her daily writing time was “a sacred thing,” and showed them where she sat every day, at the same time, for an hour or two, and wrote or didn’t write. “I love to imagine Alice Munro not budging from her writing desk, holding the line, and stubbornly and silently honouring that space and that time and that life, her writing life,” Ms. Toews said.

Ms. Munro spoke the intimate and often fractious language of mother-daughter relationships beginning with Dance of the Happy Shades, her first collection of short stories. It won the Governor General’s Literary Award for English-language fiction, the first of three Governor General’s Awards she received over the course of 14 bestselling collections.

Heather O’Neill, a Montreal novelist, poet and short-story writer, said, “I have been reading Alice Munro my whole life. She has meant different things to me at different times. No one has written about the loneliness and nakedness and sheer delight of being a woman in the way Munro has. She taught me to accept my own story, and that no matter what, a woman’s desire to be free is irrepressible.”

As Ms. Munro aged, so did her perspective on life and love in stories that became increasingly sophisticated but always accessible to her legions of fans, who read and reread her fiction for insights into their own lives and loves.

“Alice Munro is one of the four or five greatest fiction writers in English literature, ever,” said Adrienne Clarkson, Canada’s 26th governor-general. “The way she wrote, with deceptive clarity, was so extraordinary. It was a way she could catch your heart.

“There is a story of hers, Amundsen, which was originally published in The New Yorker in 2012. It’s a about a troubled female-male relationship, which she always handled so well. There is one paragraph I kept reading and rereading. The man takes her to a town and they are looking for parking outside a hardware store. Somehow in the description of the parking, you know their love affair is over. When you read every word of it, it does not say that. But you know.”

Measha Brueggergosman, the operatic soprano who championed Ms. Munro’s The Love of a Good Woman for CBC’s Canada Reads competition in 2004, said she “adored her – so humble, so gracious.”

Ms. Brueggergosman remembered going over to Ms. Munro at the televised Giller Prize ceremony in 2004, and sitting with her during the commercial break between dinner courses. “I handed her my lip gloss and said, ‘Here. Put this on, because you’re about to win.’ And, of course, she did win, for Runaway, her second Giller Prize. It’s heartbreaking to think she’ll never write another story, but we cling to and are forever inspired and challenged by the ones she allowed us to devour.”

Her long-time Canadian publisher Douglas Gibson met Ms. Munro in London, Ont., “way back” in 1974 when she had published three books at that point. “I could see that they were so good that her career was just going like a rocket, but everyone was telling her to stop writing short stories and to write novels. So, I said, ‘Alice, if everyone is telling you to stop writing short stories, they’re all wrong. You’re a great short-story writer. I’m a publisher. And if you’re to spend the rest of your career writing short stories, I’d be delighted to publish them. And I’ll never ever ask you for a novel.’”

Since then, they published 12 collections of short stories together, according to Mr. Gibson. “And with the Nobel Prize for Literature going to Alice in 2013, I guess you could say that it worked out not too badly.”

SANDRA MARTIN

The Globe and Mail, May 14, 2024