Climate change is transforming the planet, damaging the global economy and increasingly threatening human well-being, officials behind a United Nations report said on Monday.

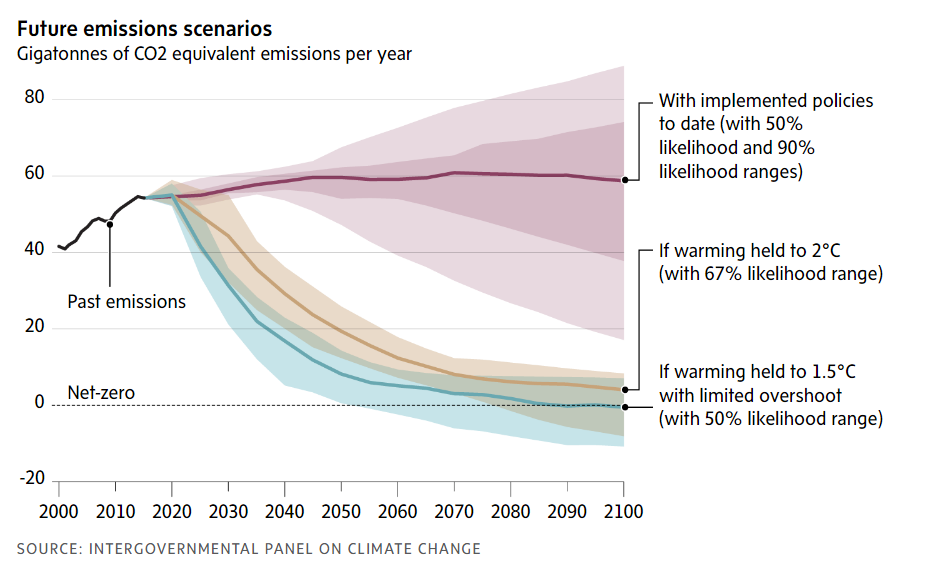

While there remains an opportunity to minimize the harm caused by fossil fuel emissions – which continue at an increasing rate with each passing year – it will take urgent action during this decade by governments and others to seize that chance and spare every region of the globe from experiencing the most serious consequences of a dramatically warmer world.

That conclusion, from the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, comes as no surprise. But in the final summary of an eight-year process by scientists, economists and other experts to determine the current state and future course of the Earth’s climate, the message has never been so well-documented.

“This report will serve as the resource for policy makers at a critical moment in history – a time when it is imperative that climate actions become a much higher priority,” said IPCC chair Hoesung Lee, at a news briefing on Monday. He and other IPCC officials spoke to reporters in Interlaken, Switzerland, where representatives have been meeting since last week to hammer out the final text of the report.

Many of the possible steps that can help improve climate outcomes and produce a more prosperous, livable world later this century are well-known, the authors say. They include smarter approaches to how we live, eat, work, build, farm and transport ourselves from place to place.

They also require stepping up our resilience as we adapt to the effects of climate change, including fires, floods, deadly heat, drought, rising seas, melting permafrost and broader more fundamental changes to the basic systems of the planet that sustain all species.

Above all, the report stresses, they require putting climate into the mainstream of policy-making at every level, to help bend the trajectory that the planet is currently on and avoid squandering investments that have already been made toward managing the transition to higher global temperatures.

“Losses and damages are part of our future,” Dr. Lee said. “But the report also emphasizes that effective and equitable climate action now can lead to a more sustainable, resilient and just world.”

The report marks the finale of the sixth global assessment of the world’s climate since the IPCC was formed in 1988. It is a synthesis of three working group reports, released since 2021, that provide detailed overviews of the physical causes, impact and options for mitigating climate change. It also incorporates three additional documents issued since 2018 that focus on the science of climate change on land and agriculture, oceans and the frozen parts of the globe, and the consequences for humanity of the average global temperature exceeding 1.5 degrees above pre-industrial levels.

The end result offers a one-stop snapshot of what is known about climate change, distilling the work of hundreds of expert authors who together reviewed thousands of scientific studies. Compared with the previous five assessments, it is also the most direct in its message – notwithstanding the fact that all 195 countries that are members of the IPCC had to sign off on the text before its release.

“The thing that has stood out most for me is the evolution of our understanding of the human influence on climate change,” said Greg Flato, a senior research scientist with Environment and Climate Change Canada, who was among the report’s core team of authors.

In the first report, released in 1990, that link was stated only tenuously, Dr. Flato said. In the current version, the human role in climate change is deemed “unequivocal” based on the scientific evidence.

And compared with earlier assessments, this one became far more pointed about what needs to be done to address the challenge.

“You can see there is a very clear sense that we can’t not talk about politics any more. We can’t just hint at it here and there,” said Matthew Paterson, director of the Sustainable Consumption Institute at the University of Manchester, who was involved in the previous assessment, released in 2014.

Politics will certainly come into play if the world is to achieve the transition away from fossil fuels that is needed to limit warming much beyond 1.5 or even 2 degrees, as specified in the 2015 Paris climate agreement.

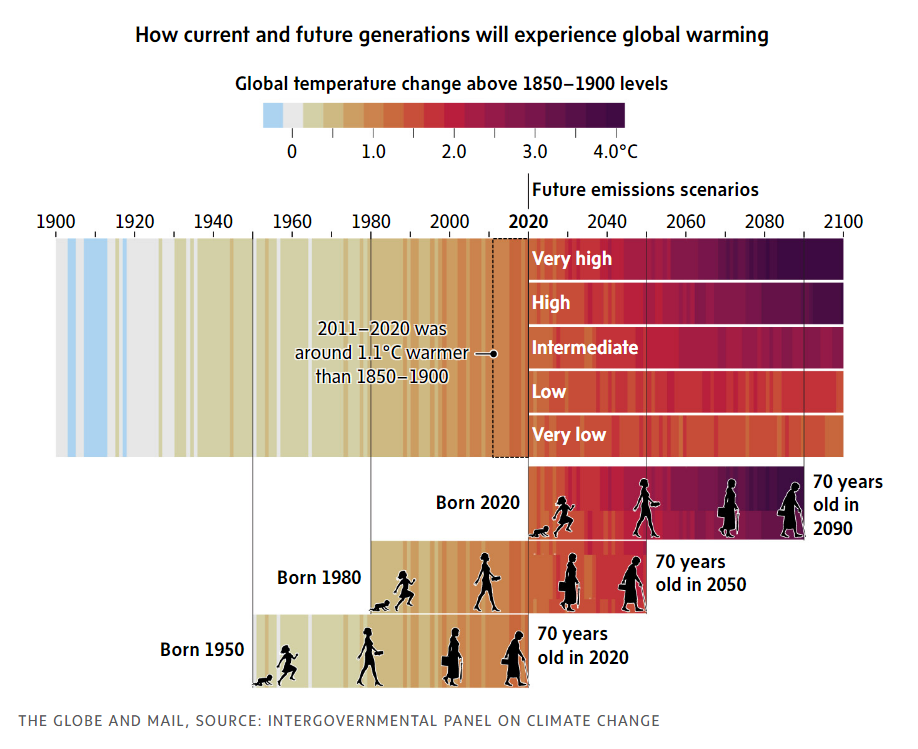

In terms of hard numbers, the scientific evidence shows that humanity is well on course to cross the 1.5 degree signpost some time during the first half of the next decade, said Peter Thorne, a report author and professor of physical geography at Maynooth University in Ireland.

“This is why the rest of this decade is key,” he said during the briefing. “The rest of this decade is about whether we can apply the brakes and stop the warming at that level.”

Among some of the report’s other main takeaways:

• losses and damage owing to a changing climate are apparent around the globe, with nearly half the world’s population living in regions that are highly vulnerable to climate change;

• the best solutions for dealing with the problem, including shifting to low carbon energy sources, will not only reduce future environmental harms but improve human health outcomes;

• increasing investments and removing financial and other systemic barriers to sustainable development will ensure that technology and human ingenuity can be applied to the problem to best effect.

The overall message from the panel is that measures taken to date to address climate change are important but not sufficient to avert a larger crisis later this century.

Nevertheless, experts who were part of the IPCC process or informed by it say there are bright spots.

Sarah Burch is a Canada Research Chair in Sustainability Governance and Innovation at the University of Waterloo and a lead author for IPCC6, writing for Working Group 3 on sustainable development.

Prof. Burch said she’s heartened by creative efforts at local, national and international levels to transform energy, food and agriculture systems.

“I’m thrilled by the growing recognition that if we want good jobs, beautiful communities, thriving nature and healthy people, dealing with climate change head on is central to all of it,” Prof. Burch said.

Valérie Courtois also sees reason for hope.

Ms. Courtois is director of the Indigenous Leadership Initiative, an Ottawa-based group focused on Indigenous-led conservation. For the past decade, ILI has been working with Indigenous communities on initiatives including Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas as well as guardian programs, in which Indigenous peoples are involved in research, monitoring and regulatory compliance activities on traditional territories.

Those initiatives are gathering momentum, reflecting research that suggests IPCAs can help Canada meet its conservation goals

The federal government has made substantial investments in Indigenous conservation, including a December, 2022, announcement of $800-million over seven years to support up to four Indigenous-led conservation areas.

“The thing that gives me hope is that I know a lot of the solutions lie with Indigenous peoples,” Ms. Courtois said.

Forests, wetlands and grasslands, often referred to as “nature-based climate solutions,” can capture and store carbon and help in mitigation by reducing the impact of flooding, wildfires or other disasters, Ms. Courtois said.

She’s also encouraged by growing global recognition of how IPCAs can play a role in improving communities’ social, physical and mental health by developing more sustainable economies. That could involve new approaches to industrial activities such as forestry.

“So that changes the entire paradigm. You’re not looking to maximize use. You’re thinking of what needs to stay for landscapes to be healthy – and what needs to stay for people to be healthy,” Ms. Courtois said.

“The number one question I ask is, ‘What needs to stay?’ – rather than, ‘What can I take?’ “

Frank Jotzo, an IPCC core team author and a professor of environmental economics at the Australian National University in Canberra, said that another positive message from the sixth assessment is that technological solutions are beginning to appear that can lead to deep reductions in greenhouse gas emissions.

“That process has got under way,” he said. “If it can continue and accelerate then the chances of keeping to lower levels of global warming are greater.”

The sixth assessment was the longest in the making for the IPCC, in part because of delays related to the COVID-19 pandemic. With its conclusion, the UN body is now set to proceed with the production of a seventh assessment, a five- to seven-year process that will officially kick off this July.

Neil Swart, a scientist with the Canadian Centre for Climate Modelling and Analysis, a federal facility based in Victoria, said that an important part of the effort will be co-ordinating results with the centre’s counterparts around the world to achieve a reliable view of where the climate is heading. As in previous cycles, the challenge will lie in properly taking into account the natural variability of Earth’s climate system as well as the choices that people and governments are collectively likely to make.

What has raised the stakes on the entire process is the growing intensity of severe weather events and their impact on people, he said.

“We’ve seen a steady increase in the request for climate information over the years,” Dr. Swart said, “but once these extreme events really started to pile on over the last few years, that demand has really peaked.”

By the time it’s completed, the IPCC’s seventh assessment is likely to reflect the growing power of computer models to provide a more fine-grained analysis of climate change in a way that can better highlight regional vulnerabilties.

William Cheung, an ocean scientist at the University of British Columbia and author on the newly released synthesis report, said those who are involved in the next cycle should also aim to look at the relationships between the larger suite of global societal challenges, including climate change, food security and biodiversity conservation.

”They are so interconnected yet they are often dealt with separately in national and international policy discussions,” Dr. Cheung said.

IVAN SEMENIUK, SCIENCE REPORTER

WENDY STUECK, ENVIRONMENT REPORTER

The Globe and Mail, March 20, 2023