As India’s COVID-19 infections mount in a crushing second wave with more than 19 million cases and counting, there is a growing clamour against media coverage criticizing Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s handling of the pandemic.

In the last week, several reports and editorials published abroad have laid much of the blame for the surge in India on the government’s failure to curb political rallies and mass religious gatherings last month. The press has also questioned why authorities were slow to prepare for the second wave despite a national panel warning of a fresh wave.

Searing images of mass cremations and burning funeral pyres spilling into parking areas as bodies pile up have drawn the world’s attention to the severity of the crisis. In India, too, newspapers have been critical of the national and state governments’ mismanagement, and there is rising resentment from the public and opposition parties on social media.

A flurry of recent directives from the government seeks to rein in the narrative that members of the ruling party and their supporters see as an attack on its public image. External Affairs Minister Subrahmanyam Jaishankar reportedly told Indian ambassadors and high commissioners posted around the globe that the “one-sided” narrative in international media should be countered, according to The Indian Express.

Last week, the Indian high commission in Australia sent a scathing rejoinder to the newspaper The Australian for republishing an article headlined “Modi leads India into viral apocalypse,” calling it “baseless and slanderous.”

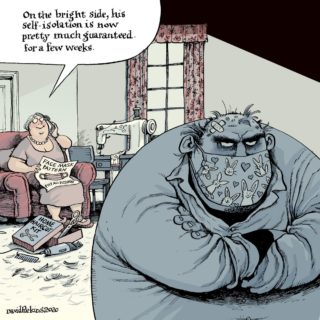

Back in India, the government issued an emergency order to Twitter to take down more than 50 tweets, including those posted by people from media, opposition party members and filmmakers. A few days later, Facebook temporarily removed posts with the hashtag #ResignModi. An open letter issued by mental-health experts called for restraint from the media in covering the crisis. “We are not saying the facts should not be reported. We are saying that hysteria and panic-inducing coverage should be avoided,” the letter said.

Media watchers said the effort to weed out critical voices covering the pandemic ties in with the growing curbs on media and digital freedom in India over the past few years. India ranked 142 in the 2020 World Press Freedom Index, down from 140 in 2019. It has also been called “one of the world’s most dangerous countries for journalists trying to do their job properly” by Reporters Without Borders (RSF).

“The co-ordinated hate campaigns waged on social networks against journalists who dare to speak or write about subjects that annoy Hindutva followers are terrifying and include calls for the journalists concerned to be murdered,” said RSF’s statement, referring to the predominant form of Hindu nationalism in India. “The campaigns are particularly violent when the targets are women,” the statement added.

The government has denied claims of curbs and blamed the low ranking on a “Western bias.” In reference to the ranking, the Minister for Information and Broadcasting, Prakash Javadekar, tweeted: “We will expose, sooner than later, those surveys that tend to portray bad picture about “Freedom of Press” in India.”

According to news reports, the government has been mulling setting up its own democracy and press freedom rankings. Meanwhile, the U.S. 2020 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices highlighted a huge number of internet shutdowns in different places across the country – 106 in 2019 and 76 times as of Dec. 21, 2020, with the longest shutdown in Jammu and Kashmir when its special status was revoked and the government feared a backlash and unrest. That information blackout was deemed illegal by the Supreme Court.

The COVID-19 crisis, in many ways, has pushed an overwhelming amount of reporting and visual evidence onto digital platforms in real time, not just from journalists.

“Social media is the most powerful platform that citizens have right now. We have been seeing Twitter and WhatsApp become a helpline for people in distress. With the collapse of governance, this kind of people-to-people communication is important and that’s what the government is trying to crack down on,” said senior journalist Geeta Seshu of the Free Speech Collective, which tracks violations of free speech and protects the right to dissent in India.

In a recent study, Arrest and Detention of Journalists in India 2010-20, Ms. Seshu noted a sharp rise in criminal cases lodged against journalists, with a majority of cases in Bhartiya Janata Party-ruled states. In the past decade, 154 journalists in India were arrested, detained or interrogated, with more than 40 per cent of these instances in 2020. Nine foreign journalists faced deportation or interrogation, or were denied entry into the country. “It has contributed to the deterioration in the climate for free speech in India,” Ms. Seshu said.

In another study, titled Getting Away with Murder, Ms. Seshu found that journalists, many from small towns working with regional media, paid with their lives for investigative reports on illegal activities. Others were intimidated using violent means. “Journalists have been fired upon, blinded by pellet guns, forced to drink liquor laced with urine or urinated upon, kicked, beaten and chased. They have had petrol bombs thrown at their homes and the fuel pipes of their bikes cut,” she noted.

Prashant Kanojia is one of them. The former journalist has had several legal cases and complaints filed against him and been to prison twice, spending 80 days in jail last year until he got bail in October. He said he has been targeted for writing articles critical of the political leadership in Uttar Pradesh.

Mr. Kanojia, who comes from a Dalit – low caste – background, says he has a fair number of followers on social media and talks about issues faced by his community.

“The government is afraid that I will provoke them to protest, even though I am not capable of doing that,” he told The Globe and Mail. “The surprising bit is that the police haven’t pursued my case after that – there hasn’t been a single hearing. That shows they have nothing substantial against me and they know the cases won’t hold up in court.”

During the pandemic, Mr. Modi’s government has clamped down on news reports that it claims were fake and created panic, calling them seditious and a criminal offence under the Disaster Management Act. It also sought to control media coverage that strayed from official statements.

Last year, the government pushed the Supreme Court to control the coverage of the pandemic. The court said it would “not interfere with the free discussion about the pandemic, but direct the media to refer to and publish the official version about the developments.”

So far, the digital news media has been freer than the more regulated TV and print news, both dependent on government advertising. “An explosion of news sites managed to make a mark in the last four to five years,” Ms. Seshu said. But in February, the government laid down a framework to regulate digital media, too.

Mr. Kanojia said his experience has disillusioned him about the profession.

“Journalism was always a passion; it never felt like a job. But looking at the current situation it’s hard to survive. There are few organizations that allow you to write what you want and I don’t find myself to be the right fit anywhere,” he said.

He said that is why he moved toward politics, as a member of a party that seeks to uphold constitutional rights.

“Journalists shouldn’t be seen as a threat but treated as part of the ecosystem,” he said.

NEHA BHATT

The Globe and Mail, May 2, 2021