Little sign of lengthy battle over old-growth logging letting up, and the RCMP says it is losing against a sophisticated, well-funded movement.

Watch: Police arrest more than 70 people at the Fairy Creek blockade near Port Renfrew, B.C., on Sept. 9, part of an ongoing standoff over old-growth logging on Vancouver Island.

The battle over old-growth logging in British Columbia shows no signs of abating, as protesters keep on coming back to Fairy Creek, in one of the largest acts of civil disobedience in the country.

In four months, RCMP have made close to 1,000 arrests on the blockades in a remote section of rain forest on southern Vancouver Island. Protesters are defying a forestry company’s logging plans, the provincial government’s efforts to broker a solution and orders of the court.

This week, the RCMP will be asking the B.C. Supreme Court for greater enforcement powers of an injunction prohibiting blockades in the area. Police say they are losing against what they describe as a sophisticated and well-funded protest movement using increasingly risky tactics.

Last Thursday, when a fleet of RCMP vehicles pulled up at the bottom of the Granite Mainline forestry road, officers faced more than 70 people sitting on the damp gravel with limbs intertwined to form a giant human knot that barred the only route to the approved logging sites on the mountainside above them.

This protest tactic is called a blob and is now familiar to the police who have spent months enforcing the court-ordered injunction on behalf of Teal Cedar Products Ltd. It took four hours for officers to tug and pry apart 71 blockaders for arrest, the largest mass arrest in a single day since enforcement of the injunction began on May 18. By the end of the day, the total number of arrests under the injunction had climbed to 962 individuals.

Granite Mainline road would not stay clear for long. The next day, another 20 people were arrested.

“Protesters have deployed increasingly extreme and dangerous methods to thwart the RCMP’s enforcement,” states an Aug. 31 application to the B.C. Supreme Court, filed by the federal Attorney-General. The tactics include individuals burying themselves under boulders and rotting logs, or suspending themselves on tripods with nooses around their necks. They’ve embedded themselves to the ground with complex devices dubbed “sleeping dragons” using concrete, chains and metal rods.

The protests are now in their second year, and supplies and supporters keep coming: During the week there are typically between 100 and 200 protesters, while the numbers climb on the weekends to more than 500.

“The present situation on the Granite Mainline is unsafe and untenable,” the application on behalf of the RCMP claims. Without the ability to set up checkpoints and search people, “the RCMP will have to re-evaluate its ability to continue to conduct enforcement operations.”

Sitting on the ground last Thursday morning amid the human blob, Shawna Knight scoffed at the notion that the police are at a disadvantage in this fight.

“That’s so funny,” Ms. Knight said as she awaited arrest for the third time. “Sophisticated? Man, it’s like, we’re using Google Maps. We just have each other. And we are persistent.”

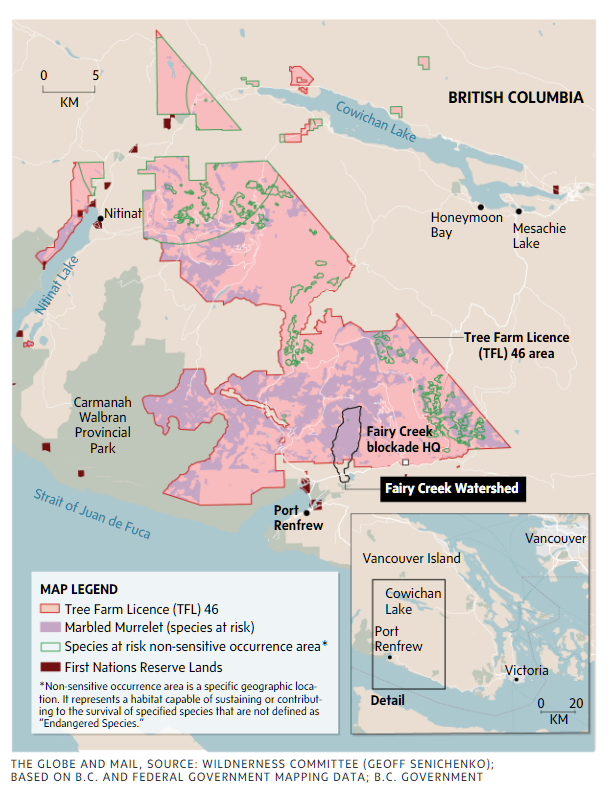

The Fairy Creek protests began in August of 2020, organized by a grassroots group called the Rainforest Flying Squad that has maintained a series of forest camps, tree sits and road blockades, northeast of the coastal town of Port Renfrew, within Teal Cedar’s Tree Farm Licence (TFL) 46, which boasts some of the largest trees in Canada and rare, intact watersheds.

The B.C. Supreme Court issued an injunction this spring that prohibits road blockades in an area that roughly mirrors the boundaries of the TFL; most of it lies within B.C. Premier John Horgan’s constituency, a not-coincidental detail that demonstrators had hoped would provoke a change in the government’s forestry practices.

Since the protests began, Mr. Horgan’s NDP government has promised to reform old-growth logging, but aside from some relatively small areas where logging has been temporarily suspended, little has changed and the province is still working on its new policy.

The Premier says his government, which has committed to implement the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, must defer to the wishes of the local First Nations, who have asked the protests to cease in their territories.

“There is a better way for B.C. to manage old-growth forests – and our government is working collaboratively with all our partners to do this,” Forests Minister Katrine Conroy said in a statement last week.

The Huu-ay-aht, Ditidaht and Pacheedaht First Nations all have a financial interest in the logging operations in their territories and reject the interference of the Rainforest Flying Squad. But the protesters maintain that their actions are supported by individual members of those communities, including Pacheedaht elder Bill Jones, who has played a prominent role in the demonstrations.

In August, the federal Liberals stepped into the fray, promising to establish a $50-million B.C. Old Growth Nature Fund if they’re re-elected. However, the protests that started in Fairy Creek now have broader aspirations, with financial implications that would easily outstrip the promised fund.

The protesters say their demands are not limited to the boundaries of Fairy Creek and the traditional territories of the Huu-ay-aht, Ditidaht and Pacheedaht. They want all industrial logging of old-growth forests in British Columbia stopped.

“It feels like we’re at the desperate point, where we are just throwing bodies between industry and the trees,” said Rachel Grigg, who was arrested on Thursday and released without charges. She said her legs were stomped on by police and that the force used against many during the arrests was unnecessary. “None of us resisted. We just held on to each other; we were holding that space.”

Ms. Grigg, who has been helping birders locate endangered species in the areas slated for logging, said she will return to the protest lines. “I feel like we don’t have a choice. This is what we have to do, to slow industry down.”

Police have rejected complaints of excessive force. In a statement Thursday, National Police Federation president Brian Sauvé said his union is considering legal action against the protesters and their supporters, saying his members have been professional despite the hazards they face enforcing the injunction.

However, the court has rebuked the RCMP over its enforcement tactics. In his written reasons published in early August, B.C. Supreme Court Justice Douglas Thompson ruled that the RCMP had overreached its authority by creating checkpoints and exclusion zones in the injunction area. “I have found that the police actions interfere with important liberties of members of the public and members of the media. … These RCMP blockades are unlawful.”

In response, the RCMP was forced to ease enforcement strategies, but now wants some of those powers explicitly laid out. The federal Attorney-General is asking the court to amend the injunction to confirm the RCMP’s powers to control access to those areas where enforcement is taking place. Specifically, that would include police authority to search people and vehicles and to deny entry to anyone carrying material that could be used to breach the injunction, and to limit vehicle and pedestrian traffic on roads leading to enforcement sites.

Teal Cedar will also be in court this week seeking to extend the injunction, which is set to expire later this month. “Unfortunately, and despite the RCMP’s considerable efforts, the blockades are ongoing,” the company says in its application to the court. “In the absence of an injunction and enforcement by the RCMP, anarchy will reign in and around TFL 46, a situation which cannot be tolerated in a society governed by the rule of law.”

The company has managed to conduct some logging throughout the blockades, but only with significant police resources. The RCMP spent two weeks actively enforcing the injunction to dismantle one blockade in the Caycuse watershed before the company could log there. But the blockade at Fairy Creek was more persistent, and every time it was cleared by police, the protesters returned in numbers and reclaimed the road.

Diana Mongeau, a senior who has been part of the blockades since the first day, noted she and others have been invited to stay by Mr. Jones, the Pacheedaht elder. “We show up because we want something bigger than ourselves,” she said. People are willing to be arrested because they want to save the ancient forests, she said as she stood at the foot of Granite Mainline.

“We thought it would force change. We thought the NDP would keep their promises,” she said. That hasn’t happened yet; and she is still welcoming new recruits, and supporting those who are arrested. “They know we need this for our planet to survive. I don’t know why the NDP government isn’t listening to us,” she said. “But we are not going away.”

JUSTINE HUNTER

The Globe and Mail, September 13, 2021