The Globe and Mail explores some key questions as Canadians endure weather that one climatologist described as ‘almost biblical’.

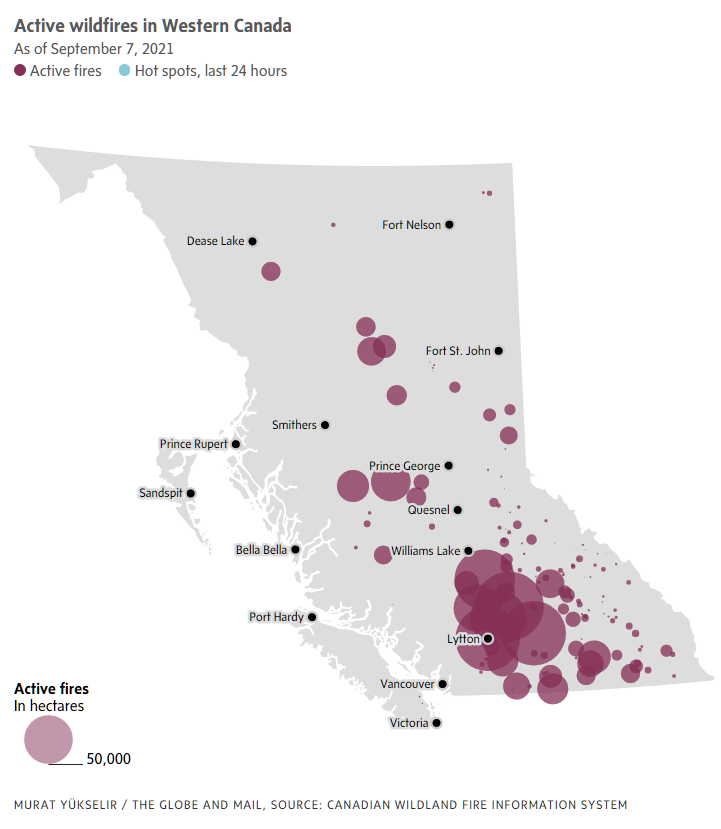

The B.C. village that set a Canadian heat record last week, at a scorching 49.6 C, went up in flames beneath a high-pressure weather system wreaking such havoc that one climatologist described the situation as “almost biblical.”

First came extreme heat in the Fraser Canyon town of Lytton, then came the wildfires – a cascade of climate-change disasters that has captured international attention. “Heat records are usually broken by tenths of a degree, not 4.6 C,” Swedish climate activist Greta Thunberg tweeted, referring to the previous Canadian high of 45, set in Saskatchewan in 1937. “We’re in a climate emergency that has never once been treated as an emergency.”

In the Pacific Northwest, wildfires are burning, power grids are failing, transit systems are melting and people are dying. Between June 25 and June 30 alone, the BC Coroners Service received 486 reports of sudden and unexpected deaths – a 195-per-cent increase over the approximately 165 deaths the service would see in a typical five-day period. Once locked over the West, the system has moved eastward, with Environment Canada heat warnings in effect in parts of Ontario and severe thunderstorm warnings in southern Quebec.

“People ask, ‘Is this the new normal?’ ” said Courtney Howard, an emergency physician in Yellowknife and former president of the Canadian Association of Physicians for the Environment. “It’s not the new normal. It’s going to continue to get worse for the next few decades.”

While weather is naturally variable, this kind of heat event is made ever more intense – and will occur with increasing frequency – because of climate change. Here, The Globe and Mail explores some key questions as Canadians confront the loss of life and landscape.

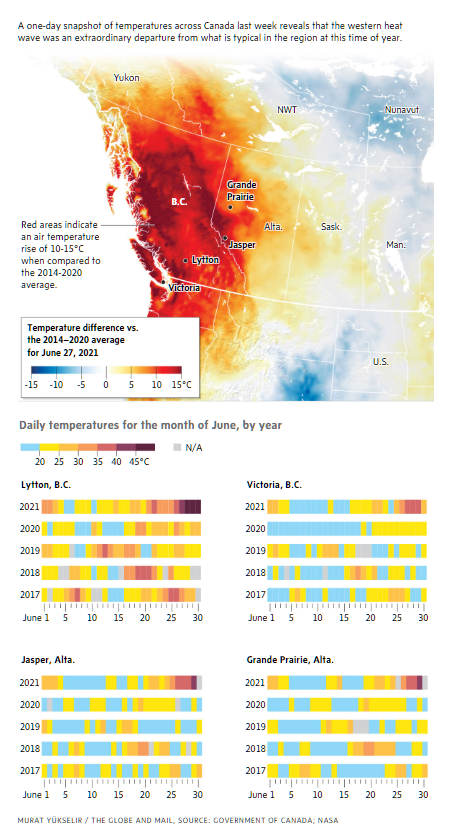

How hot did it get in B.C.?

Why was it so hot?

Several factors conspired to keep a massive ridge of warm air parked over the Pacific Northwest last week. Meteorologists call this effect a “heat dome” because the warm air is trapped in a circulation pattern that prevents cooler air from moving in.

This year, an unseasonably dry spring in the region has served to amplify the high temperatures. With so little moisture in the environment, solar energy that might otherwise have gone into evaporating water has instead been making hot air even hotter. And while the giant weather system is heading eastward, its movement was slowed by a wavy pattern in the jet stream called an “omega block,” which allowed temperatures to soar in the same locations each day with little or no relief at night.

How unusual is this?

A heat dome is not unusual, but the scale and impact of this latest one has literally been off the charts. That much is obvious from the shattered temperature records the system produced in hundreds of locations. For example, Victoria, which has one of the mildest climates in Canada, has an average June high temperature of 20. On June 28, it reached 39.8 – a full nine degrees higher than the city’s previous record, set in 2015.

Just as striking is the scale of the high-pressure ridge, which stretches from Death Valley, Calif., to the Arctic Circle and has reached altitudes comparable with those of commercial aircraft. What weather experts say is even more astounding, though, is the fact this pattern is occurring now.

“Generally, the warmest moment of the year in a province or city comes much later, in July or August, not in June,” said David Phillips, senior climatologist with Environment and Climate Change Canada. He added that having so many temperature records broken so early in the summer, accompanied by flood warnings because of sudden snow melt on mountain peaks, has put this week in a class by itself in the annals of Canadian weather. “I mean, it’s almost biblical,” he said.

How does extreme heat affect infrastructure?

Amid high temperatures in late June, Calgary Transit shut down its public WiFi service at its light-rail stations to avoid damaging equipment – a minor indication that much of our transportation infrastructure was not built for extreme heat. When extremely hot, rails can bend and buckle to form “sun kinks,” which can cause derailments. In a statement, CN said it “uses advanced rail metallurgy and rail properties, along with a variety of standards, policies, and operating procedures to mitigate risks associated with thermal expansion.”

Power grids are not immune either. A 2015 study by Toronto Hydro noted that high temperatures (particularly above 40) affect power transformer capacity and electrical transmission efficiency. That can cause transformers to fail.

During the latest heat wave in the West, electricity demand skyrocketed when large numbers of people turned on their air conditioners simultaneously. BC Hydro said it was able to meet the record-breaking demand thanks to its hydroelectric dams, which can ramp up quickly. But not all utilities enjoy such flexibility; indeed, BC Hydro said its trading subsidiary, Powerex, exported so much electricity to neighbouring U.S. states lately that volumes approached the system’s transmission limits. Generally, Canada’s own interprovincial transmission capacity is even more limited, restricting provinces’ abilities to assist each other during extreme events.

Meanwhile, when the heat dome moved eastward, the Alberta Electric System Operator asked residents to conserve energy – especially between 4 p.m. and 7 p.m. – although the system has yet to fail during the heatwave.

Utilities, public transport authorities, freight railways and others are beginning to consider how extreme heat will affect Canada’s power grids, transportation networks and other infrastructure. But “I don’t think it’s been a huge focus of adaptation up until recently,” said Joanna Eyquem, managing director of climate-resilient infrastructure at the Intact Centre on Climate Adaptation. The federal government recently launched the National Infrastructure Assessment, an initiative intended to support increasing the resilience of infrastructure across the country to climate change (the public engagement process ended June 30). Extreme heat impacts are among the issues to be considered.

In addition to extreme heat, wildfires can also affect infrastructure – and not just in obvious ways. During unprecedented fires in 2014, Stanton Territorial Hospital in Yellowknife had to cancel elective surgeries for about a week because of air quality concerns in the operating room. The ventilation system, Dr. Howard said, was drawing in air – and smoke – from outside. “They weren’t thinking about that possibility when they built it,” she said. (A new hospital has since been built in Yellowknife. A spokesperson for the Northwest Territories Health and Social Services Authority said the new hospital’s ventilation system is capable of recirculating inside air, if required, to improve air quality.)

If this is bound to happen more often, how do we cope?

There are things individuals can do, and there are things companies and governments can do.

At the personal level, only about a fifth of households in the Vancouver region had air conditioning in 2017, according to the most recent Statistics Canada data. The rates in Calgary and Edmonton are only slightly higher, at 24 per cent and 29 per cent respectively – still well below the national rate of about 60 per cent. That will have to change. Cities will have to ensure they have adequate space at cooling centres, particularly for people experiencing homelessness or without access to air conditioning.

People can also install heat-resistant curtains in their bedrooms and ensure that any outdoor space they may have, including a balcony, has some greenery. Artificial surfaces such as concrete absorb and re-emit the sun’s heat more than natural landscapes – a phenomenon known as the urban heat island effect. The difference in daytime surface temperatures between urban and rural areas can be as high as 15 degrees.

“Even if you stand on your patio versus your lawn, you’ll notice a difference,” Ms. Eyquem said.

This is why cities such as Quebec have created parking lot standards that suggest ways to reduce the surface area of the lot, revegetate the space and use materials with a high solar reflective index. Cities can also protect their natural assets, such as river valleys and tree canopies, which provide cooling benefits. “We need to invite nature into the city more to help cool our urban areas,” Ms. Eyquem said.

In addition to these tangible steps to keep people and spaces cooler, Dr. Howard said Canadians must also take care of their mental health as anxiety around climate change takes hold. “It’s normal for extreme weather events like this to be a trigger for people to take a look at the world, their place in it and what climate change means for their children,” she said. “You can’t just take a yoga breath and hope for the best. You have to take action. That’s where we’re at now.”