The Bank of Canada is shifting its focus to NAFTA’s possible demise as it ponders what comes next after pushing its key interest rate to the highest level since the last recession.

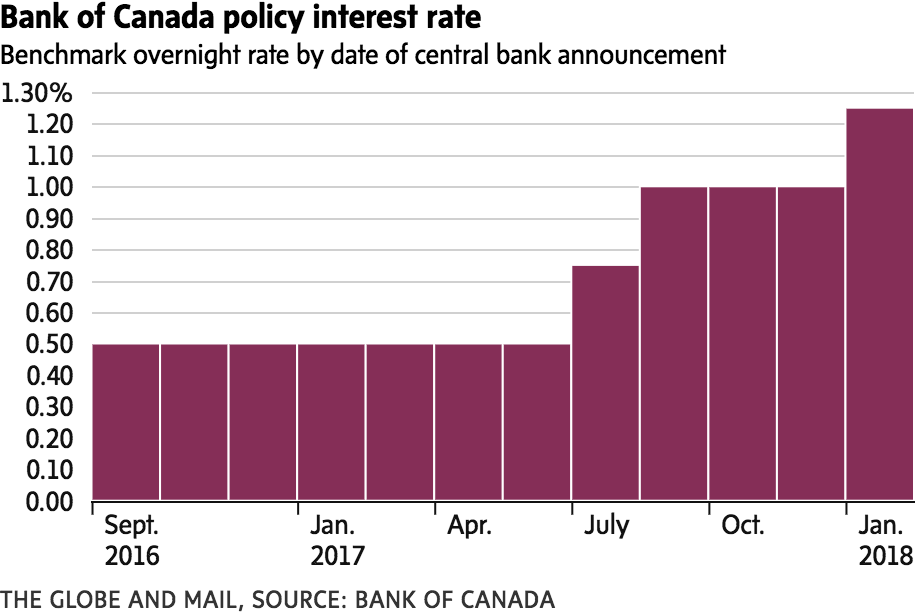

The central bank hiked its benchmark rate by a quarter-percentage-point to 1.25 per cent on Wednesday, citing a string of upbeat news, including an economy that’s running flat out, healthy job gains and the lowest unemployment rate since 1976.

It was the Bank of Canada’s third rate hike since last summer and is the first time the overnight rate has been above 1 per cent since 2009.

But good economic news may be mainly in the rear-view mirror.

The economy is expected to slow significantly this year and Canada’s vital trading relationship with the United States is under threat as talks to renegotiate the North American free-trade agreement resume next week in Montreal.

“Uncertainty about the future of NAFTA is weighing increasingly on the outlook,” the bank said in a statement on the rate decision.

The NAFTA talks could now affect the pace and timing of the central bank’s next rate hike. Investors are currently betting the bank will do nothing at its next meeting in March and then move again in April, although the odds of a spring hike have slipped a bit since Wednesday’s move, according to Bloomberg.

“By making NAFTA risks so prominent in this statement, rate hike odds will now ebb and flow with the negotiations,” Bank of Montreal chief economist Doug Porter said in a research note.

Many economists expect the central bank to raise rates at least two more times this year.

In an interview Wednesday with Business News Network, Bank of Canada Governor Stephen Poloz said high levels of household debt have made the economy more susceptible to the effects of rate hikes – and that high debt is constraining the pace of increases. “It’s a force acting on the economy that would prevent us from getting interest rates all the way back to what people consider to be neutral,” he said.

The end of ultralow interest rates is already squeezing Canadian borrowers. Most major lenders raised their rates on mortgages and other loans in the days before Wednesday’s widely expected central bank rate hike. That has pushed the posted rate on a five-year fixed rate mortgage above 5 per cent for the first time in roughly four years. Under new federal stress-test rules, higher posted rates make it harder for homeowners to qualify for mortgages.

Canada’s economy, which remains highly dependent on debt-fuelled spending and real estate activity, could be upended as interest rates move higher, argued David Madani, an economist at Capital Economics in Toronto. He said the Bank of Canada is underestimating the hit to borrowers from higher rates and tighter mortgage rules. These factors could eventually force the central bank to roll back its recent rate hikes.

Canadians are among the most indebted people in the world, carrying an average of $1.68 of credit for every $1 of disposable income.

Some analysts say trade uncertainty could lead Mr. Poloz to hold off on additional rate hikes until the summer. But if the NAFTA talks are extended beyond Mexico’s July 1 presidential elections, Mr. Poloz could also opt to move sooner, Mr. Porter said.

The Bank of Canada’s base-case assumption is that NAFTA will survive. But the bank has put a NAFTA discount on its growth forecast because the uncertainty is already putting a chill on investment in this country.

Mr. Poloz told reporters that companies are already investing less in Canada for fear of being caught on the wrong side of a higher tariff barrier.

“That’s already happening today,” Mr. Poloz said. “It’s being delayed or redirected to the U.S.”

Senior deputy governor Carolyn Wilkins added that the central bank would “adjust monetary policy in a timely way,” depending what happens to NAFTA.

Trade uncertainty is already affecting investment by U.S. and European companies in Canada, which have been making fewer new investments here since mid-2016, the central bank said in its latest Monetary Policy Report, also released Wednesday. The bank said the uncertainty will cut business investment over the next two years by as much as 2 per cent. That translates into a drag of 0.3 per cent a year on economic growth – a slightly larger hit than the bank estimated in October.

The central bank’s latest forecast, also released Wednesday, predicts economic growth will slow significantly to 2.2 per cent this year and 1.6 per cent in 2019, down from an estimated pace of 3 per cent in 2017.

The bank pointed out that roughly half of Canada’s exports to the United States benefited from preferential NAFTA tariffs in 2016. The United States buys roughly three-quarters of what this country exports.

The Bank of Canada said it remains “cautious” about raising rates further. “While the economic outlook is expected to warrant higher interest rates over time, some continued monetary policy accommodation will likely be needed to keep the economy operating close to potential and inflation on target,” according to the statement.

Beyond the NAFTA worries, most economic pieces are falling into place for the Bank of Canada. Inflation has inched up to near the bank’s 2-per-cent target and should stay close to that level over the next two years, in spite of “temporary” volatility in energy prices over the next few months, the bank said.

Going forward, the engines of growth for the economy will be business investment and exports, rather than consumers and home construction, according to the bank. That’s largely because of higher interest rates and the tighter mortgage rules put in place this month.

BARRIE MCKENNA

The Globe and Mail, January 17, 2018