Veronika Irvine graduated from university with a master’s degree in computational chemistry, but she ended up in computer science. It was the mid-1990s, and she was armed with one course in the field and a relative in the industry.

“At that time, there weren’t that many computer science graduates, so it was much easier to find a job,” said Ms. Irvine, who is now studying for a PhD in the subject at the University of Victoria. She landed at Bell-Northern Research (BNR), which eventually became part of Nortel Networks.

“We used to call BNR the training ground. … They had amazing courses internal to the company. When I started, there was a whole new paradigm of object-oriented [computer] programming that was not covered by many courses in university. But BNR wanted to use it and they trained us,” Ms. Irvine said.

The world where Ms. Irvine worked for more than a decade, where firms invested heavily in educating employees, has been in decline, says a new report from the Council of Canadian Academies to be released on Thursday morning. It cites figures showing that, since 1993, Canadian employers have decreased investment in basic training per employee by 40 per cent. And in recent years, industry and governments have said Canada’s trailing global performance in innovation and productivity is due to shortages of skills in science, technology, engineering and math, commonly known as STEM fields.

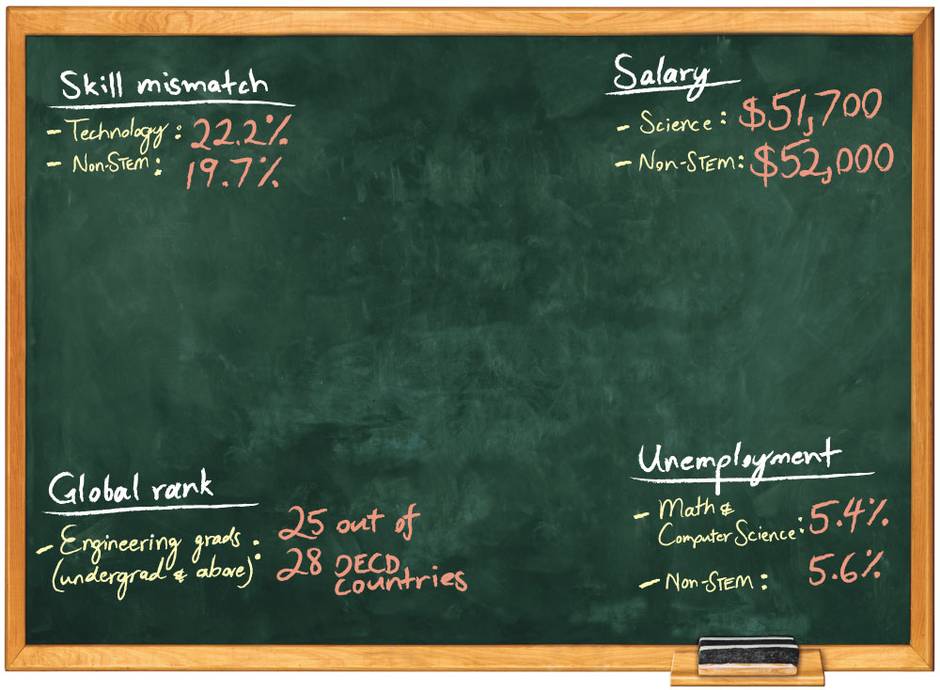

Yet the panel finds little evidence of a shortage of such skills nationally. And after reviewing hundreds of national and international studies on innovation, it also finds that science and tech are not magic ingredients.

“Having the right technical skill capacity is very important for innovation, but there is no evidence that the lack of STEM skills is constraining our innovation. What we don’t know is what the right formula is to get innovation,” said David Dodge, chair of the 11-member panel that studied the issue for Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC).

While the report contains few specific policy prescriptions, it has profound implications for a range of initiatives, including investing more in early science education and less in postsecondary science training. Rather than pump out highly trained minds to fill temporary or regional labour market gaps, governments and the education system must ensure students have a foundation in math and science skills from an early age, the report says.

“The right thing to do is to build skills from the ground up, so that the whole economy is nimble. As the next big technology comes along, we are part of developing that,” said David Green, an economics professor at the University of British Columbia who was on the panel.

Governments that try to read the economic tea leaves to create employees for today are likely to fail, he said. Private firms, which are what the report calls the “agents of innovation,” will know what gaps in knowledge they face.

“In the direct post-war period, it seemed somewhat easier to see what it is that you were trying to do in terms of developing heavy industry and so on,” Dr. Green said. “…As the rate of innovation increases, it becomes even more of a mug’s game trying to be the one choosing what the next trend is going to be.”

Last week, a report by the United States National Science Board made similar recommendations.

Ms. Irvine, who has taught elementary and high-school students how to make digital art through computer programs, agrees. She says the world is at an educational juncture as important as the rise of mass literacy.

“Once upon a time, generations ago, not everybody could write. If you couldn’t write, you couldn’t have your ideas expressed wider than to just the people you talked to, and have your idea spread. I feel the same thing is happening in the world with technology. If you can’t write a computer program, then you are heavily dependent on someone else.”

Building fundamental science and tech skills is crucial because graduates with those degrees are increasingly working in non-STEM fields and vice-versa.

“In the most productive firms and across the economy, it is the interaction between the people with the specific training, working with people who are working in other areas that seem to contribute to productivity,” Dr. Dodge said.

For Ms. Irvine, that has meant combining the skill of a childhood hobby – lace-making – with math. She has created a computer program that chooses possible lace patterns from millions of possibilities. From the results, she produces bobbin lace by hand, which she has exhibited in art shows. A similar type of computer alogorithm could have applications in designing secure networks online.

Kyle Cameron, who has a degree in chemistry from Dalhousie University and considered doing graduate work in the field, says he carried his science training into his acting career.

“The science served me well, and it was also to my detriment,” said Mr. Cameron, who is rehearsing for the premiere of Trouble Cometh at the San Francisco Playhouse. “I had the kind of mind that allows me to be a scientist and I brought that approach to the theatre. I would break down a scene and a character. It was very critical, very analytical. It took me a long time to let a piece of art, a poem or a sculpture just wash over me,” he said.

Science graduates working outside STEM fields, however, can mean lost earnings and economic potential, some say. According to a report on underemployment this winter from the Ontario Society of Professional Engineers, only about 40 per cent of Canadian-educated male engineers actually were working in the field.

The report succeed if it helps develop graduates who have technical and complementary skills such as sales and entrepreneurship, said Susan Holt, president and CEO of the New Brunswick Business Council, also a member of the council panel.

“What’s in Canada’s best interest is the long-term view where we provide critical, fundamental skills at the earliest levels, entrepreneurial skills to unlock their potential, and create flexible people that are ready for an unpredictable labour market.”

REACH, RETAIN UNDERREPRESENTED GROUPS

Rather than stress efforts to increase the number of science graduates, governments and industry need to work together to bring in more underrepresented groups, who, even when they have science credentials, are less likely to see the same returns from their education as white male graduates, says a new report from the Council of Canadian Academies.

Women and aboriginals are two of the groups identified in the report.

“We have to find ways to tap into that human capital stock that is here but has not been invested in,” said David Green of the University of British Columbia.

Steady and early intervention in drawing more members of these groups to science and tech have yielded results. This fall, for example, one-third of the University of Toronto’s first-year engineering class is female. Engineering dean Cristina Amon says that number – an increase from 20 per cent a decade ago – is partly due to outreach. The university offers courses in basic engineering to elementary and middle-school students, and has female students visit high schools.

“We hear from our applicants that they like to see strong female role models,” she said.

Other groups have engaged young children by allowing them to explore a science topic in which they are interested before they are exposed to formal concepts.

“By starting with the premise of innate interest, it becomes a lot easier to keep kids engaged in learning,” said Bonnie Schmidt, the founder of Let’s Talk Science, a national non-profit that delivers science courses and workshops to children, including in the North. “In the Arctic, it’s working with the local communities to identify some of the issues and getting the kids involved in things that would be of relevance to them,” Dr. Schmidt said.

Starting early is particularly important for reaching and retaining underrepresented groups, David Dodge said.

“If you had to pick one thing to do to enhance our longer-term growth, it would be to put more emphasis on enhancing the building of mathematical, technical and creative skills of folks at the level of the schools. … That would be particularly true for aboriginal [children]. Without the background and education, they can’t even get onto the first rung of the ladder.”

LESSONS FROM THE DOT-COM BOOM

What are the drawbacks of trying to time the labour market? To answer that question, the Council of Canadian Academies report repeatedly refers to the dot-com boom and bust as an example. Facing what were believed to be permanent shortages of labour, IT industries advocated for and won the entry of workers from abroad. Universities expanded their programs in computer science and increased enrolment.

When the bubble burst, it was individuals who had to adapt.

Tim Lam, who graduated from Ryerson University in computer science in 2004, first found part-time work at his alma mater.

“I knew that I would have to work my way up, but the prospects were few and far between. Employers wanted at least two years of experience.”

Mr. Lam, who is now an independent consultant, had always planned to go to graduate school, and he completed a master’s degree while working.

“The extra credential won over more employers, and I was able to land a job that paid 40 per cent more,” he said.

Others left computer science after experiences in the depressed job market. In 2001, the only job Shamus Pikk could find was in a call centre. It was a far cry from what he expected before graduation, when it looked like he would have his pick of employers.

In the 1990s, “large Silicon Valley-based companies came to our campus and showcased themselves, hoping that the best graduates would apply for positions at their firm,” Mr. Pikk said in an e-mail. “We … were even pursued by credit card companies during pregraduation on-campus job fairs to open large credit lines to buy expensive toys (cars, electronics) as graduation gifts for ourselves.”

He moved from the call centre to a job in the financial industry, and says he uses few of his technical skills.

Such stories are precisely why the report stresses the importance of complementary skills such as communication, teamwork and leadership alongside scientific know-how.

“Innovation and productivity, those are long gains. If you turn your efforts sideways to go after each regional or industrial disequilibrium that comes along, you are going to miss the long game. That’s what happened in the dot-com boom and bust,” said David Green of the University of British Columbia.

SIMONA CHIOSE – EDUCATION REPORTER

The Globe and Mail

Published Thursday, Apr. 30 2015, 5:00 AM EDT

Last updated Wednesday, Apr. 29 2015, 9:48 PM EDT