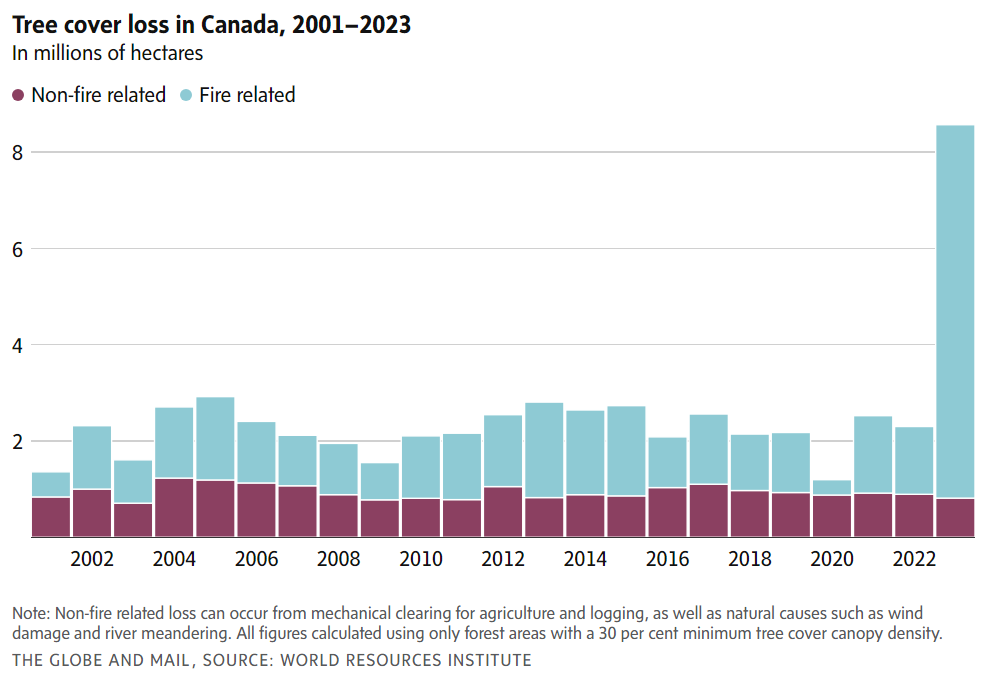

Canada lost a record 8.6 million hectares of forest last year – more than 90 per cent of that owing to wildfire, according to an analysis released Thursday.

The satellite-derived data, produced by researchers at the University of Maryland, showed that the swaths of forest burned in Canada in 2023 represented one of the largest anomalies witnessed since they began collecting the data globally in 2001. They dubbed it the world’s “most concerning fire story” of the year.

The surface area burned across Canada last year “is three, four and five times greater than any individual preceding year,” said Matthew Hansen, a remote sensing scientist who leads a lab at the university that studies changes on the Earth’s surface.

The findings were released by the World Resources Institute’s Global Forest Watch online platform on Thursday as much of the country faced conditions similar to those that exacerbated last year’s punishing fire season, including drought and unseasonably warm temperatures. The latest Canadian Drought Monitor, from the end of February, reported much of Alberta and pockets of Saskatchewan and British Columbia were suffering “extreme” or “exceptional” drought. Nearly three quarters of the country was classified as “abnormally dry.”

Canada is rarely singled out by the World Resources Institute in its discussions concerning forest loss. The organization, which produces a wide range of research and data concerning food, energy, forests and climate, usually focuses on tropical countries with globally significant forests, such as Brazil, Colombia and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Although Canada’s forest loss was more than double the total loss observed throughout the tropics, Prof. Hansen warned against comparing the two. A square kilometre of tropical forest contains more biomass than does an equivalent area of boreal forest, the type which dominates more than half of Canada’s land mass.

Canada’s overall forest loss last year, though widely described as record-breaking, had only a negligible impact on the country’s vast overall forest cover. In the Canadian Forest Service’s latest annual report on the state of Canada’s forests, released last month, Canada had 367 million hectares of forest at the end of 2022, so last year’s burn scars (as calculated by the World Resources Institute) represent more than 2 per cent of the total.

Over the past 50 years, according to federal data, the average area burned has been 2.3 million hectares annually. The previous record was set in 1989, when 7.6 million hectares burned.

The federal report forecast Canada’s forest area will remain stable in the future, as it has been for decades.

The federal government reported a much higher area burned last year than did the World Resources Institute: 15 million hectares, or about 4 per cent of all forested area. Piyush Jain, a research scientist with the Canadian Forest Service, said more than one million hectares of that forest had burned previously within the last 20 years, another first in the historical record.

“There is a question of whether Canada’s forests could sustain many years like what we got in 2023,” he said.

In 2021, at the United Nations Climate Change Conference in Glasgow, 144 countries, including Canada, signed a declaration stating that they would work collectively to halt and reverse forest loss by 2030. The data from Global Forest Watch suggest little progress has been made. Worldwide, tropical forests diminished by 3.7 million hectares – an area slightly larger than the Netherlands. The rate of loss is equivalent to destroying 10 soccer fields per minute.

Deforestation rates decreased significantly in Brazil and Colombia, where new political leaders emphasized forest conservation. But that progress was offset by accelerating losses in several countries, including Laos, Bolivia, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Nicaragua. Last year’s decline was consistent with the range of three million to four million hectares of tropical forest lost annually over the past two decades. Major drivers of tropical forest destruction include expansion of agriculture and fires, including ones deliberately set by people.

With fewer than six years remaining, the World Resources Institute said the world remains far off track to attain the 2030 target for halting forest loss set in Glasgow.

MATTHEW MCCLEARN

The Globe and Mail, April 3, 2024