After a slump in consumer prices during the pandemic, they’ve come roaring back as demand increases and supplies of some goods get scarce. Here’s what you need to know.

WHAT IS DRIVING INFLATION?

Probably the biggest factor in this year’s inflation surge is simply the reality that consumer prices fell to unusual lows last year, and it’s against these low prices that we are measuring the current price environment. This is what economists are talking about when they refer to “base effects.”

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, huge swaths of the global economy were shut down and consumers were told to stay home; demand for many goods and services plunged and prices slumped. Since inflation is typically calculated as a year-over-year change, it’s against these lows that we have been comparing the current prices, which have increased substantially as pandemic restrictions have eased. The pronounced weakness of the year-earlier comparisons have magnified the price gains in the annual inflation rate.

But there’s more to it than just a statistical quirk. The rapid reopening of many sectors of the economy has unleashed a flood of demand from consumers, which has been exacerbated by the unusually large stockpiles of household savings that built up during the pandemic.

Around the world, manufacturers, transporters and retailers have had tremendous trouble keeping up with demand. In addition, the pandemic has shifted consumer preferences to different products – home office equipment, bicycles, bigger houses in the suburbs, just to name a few – and suppliers haven’t been able to keep pace with these rapid shifts. The result has been supply shortages in numerous consumer goods as well as the raw materials to make them – driving up prices.

HOW DOES THE CURRENT CANADIAN INFLATION RATE COMPARE HISTORICALLY?

The August consumer price index (CPI) inflation rate is 4.1 per cent, up from 3.7 per cent in July. The last time the rate was higher was in March, 2003 (4.2 per cent), during a temporary surge that was another case of base effects – namely, a slump in year-earlier gasoline prices.

But from a broader historical perspective, 4.1 per cent is, comparatively, nothing. Inflation was north of 10 per cent in the mid-1970s and again in the early 1980s. In the early 1990s, when the Bank of Canada formally adopted maintaining low and steady inflation as its primary monetary policy objective, inflation still hovered around 5 per cent. But since the central bank set its inflation target at 2 per cent in 1995 – using interest rates to help steer inflation toward that rate – inflation has averaged very close to that target.

WHAT TYPES OF PRODUCTS OR SERVICES ARE MOST AFFECTED BY INFLATION?

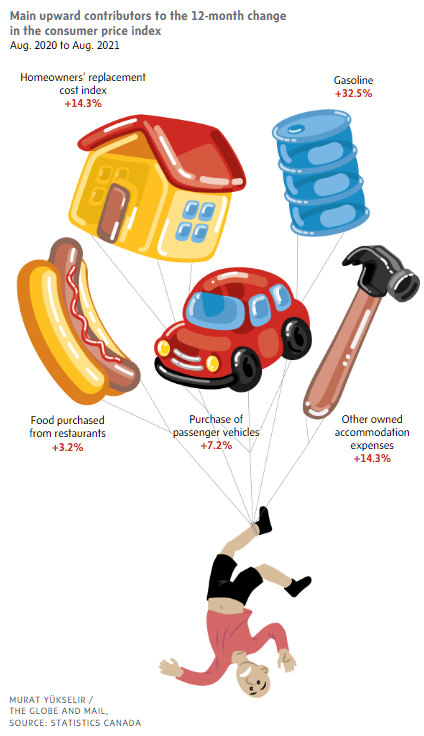

The August CPI data from Statistics Canada show that goods (up 5.8 per cent year over year) have seen much higher inflation than services (up 2.7 per cent). The big contributor has been gasoline, up more than 32.5 per cent from a year earlier, when prices were severely depressed by pandemic shutdowns. Home replacement costs were up almost 14.3 per cent, reflecting the surge in prices for homes in the past year.

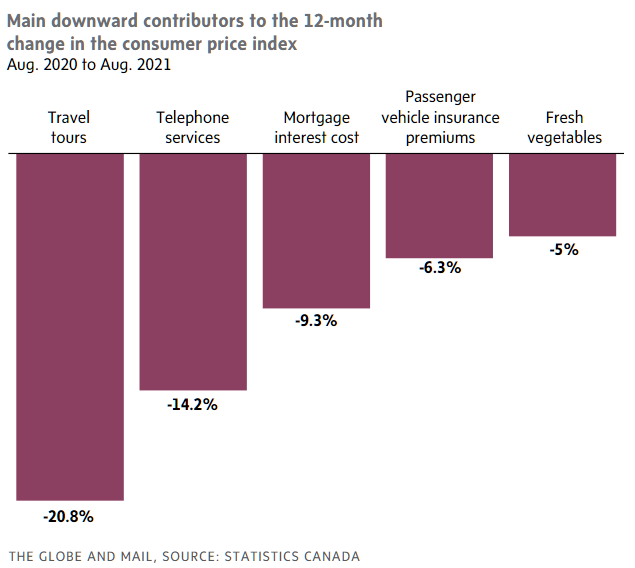

On the other hand, prices for some things have declined significantly in the past year. Mortgage interest costs were down 9.3 per cent in August from a year earlier, reflecting deep rate cuts that the Bank of Canada made last spring to aid the economy in the face of the pandemic. The price of telephone services was down 14.2 per cent. Travel tours are down 20.8 per cent year over year.

If you’re spending, be inflation-aware. Consider planning your renovation for next year or 2023 in hopes prices for building materials ease back. Lumber prices have come back down, but other costs may still be elevated. Prices for new and used cars have been on the rise as people resume driving farther than the local grocery store. Where possible, keep your existing ride for another year or so until the post-pandemic vehicle-buying rush dies down. Grocery inflation is expected to continue through the rest of the year. If you’re able to buy in bulk, you may be able to dodge some future price increases.

IS THERE A ‘WINNER’ IN INFLATION?

There are some investments that have performed well in past periods of inflation. Gold is one example, while others are commodities like oil and metals. Real estate is also considered a good hedge against inflation. You can get exposure to real estate by investing in real estate investment trusts.

WHAT WILL BRING INFLATION DOWN?

Time – at least for a significant portion of the increase. Over the next few months, the year-over-year price comparisons will become less stark, as the price recovery from the earlier COVID-19 shutdowns increasingly works its way into the year-earlier numbers. For example, the average national price of gasoline in August, 2020, was $1.06.6 a litre; by mid-February of 2021, it was $1.20. In addition, we can expect unusual price pressures caused by the sudden reopening of many sectors of the economy to ease, as the initial rush of demand moderates and activity returns to normal.

Many economists believe that the high prices themselves will help solve the inflation situation, as it adds incentive to producers to increase their capacity. This will take time, but as supply catches up with demand, price pressures will dissipate.

From a policy standpoint, the biggest weapon lies with the Bank of Canada. If inflation remains persistently high, the central bank will eventually step in and raise its key interest rate from the current record low of 0.25 per cent. The bank has already taken other actions to reduce the amount of stimulus that its monetary policy is injecting into the economy – specifically, it has gradually reduced the amount of government bonds that it has been buying on the open market since the COVID-19 crisis began.

Interest rates are considered the bigger weapon to slow inflation; but the bank has said that it doesn’t want to turn to rate hikes until the economy has returned to full capacity. Based on the bank’s latest projections, that is unlikely before the second half of next year. In the meantime, the central bank is willing to tolerate inflation in the 3-per-cent range – which actually represents the top end of its tolerance band around its target of 1-to-3 per cent, designed to give it some flexibility when inflation gyrates. But if inflation stays above that band for uncomfortably long, the bank may start leaning toward acting sooner rather than later.

A key question is how much of this is temporary, and how much may be permanent. While economists are generally confident that a substantial portion of the recent inflation surge will pass as things return to something approaching normal in the coming months, it’s clear that at least some of these price pressures may be longer lasting.

The Globe and Mail Staff, September 15, 2021