The American immigration ban that is the subject of a battle between Donald Trump and the country’s courts has mobilized universities around the world because it strikes right at the heart of the principles of higher education, Canadian universities say.

Under an executive order signed by the U.S. President, citizens of seven predominantly Muslim countries were temporarily barred from entering the United States. A federal judge has suspended the President’s order for now, but the ban has led Canadian universities to rapidly mobilize to open admission or research labs to students and faculty left stranded by Mr. Trump’s actions. Many say the measure is a fundamental threat to the free exchange of ideas and compels them to help those affected while raising their voices to oppose the order.

“Education transcends borders, it’s where you share ideas, you develop research together,” said James Mandigo, the vice-provost for enrolment management and international at Brock University in St. Catharines, Ont. “Excluding people from that discussion, particularly the most vulnerable, sets us so far back.”

Like other Canadian university leaders, Dr. Mandigo began trying to understand the effects of the ban on campus the weekend it was announced. The first task was to find out how many students belonged to one of the nationalities the order identified. Brock, he discovered, has close to 70 undergraduate and graduate students from the seven countries. (At the University of Calgary, it is 300 students. At Simon Fraser, it’s 450 students. Nationally, roughly 3,500 students from the seven countries have been issued visas for the last three years, with the majority coming from Iran.)

After the shooting in Quebec City last week, in which six people died while praying in mosque, the concerns over the impact of the immigration ban grew to worries about how to extend psychological support to Muslim students on campus.

“We had concerns about their safety on campus and around their belonging,” said Dru Marshall, provost at the University of Calgary. “What are the concrete things that universities and us are doing to combat Islamophobia?”

One of the most important ways universities have stressed they will uphold the values of openness and tolerance is by making it easier for those affected to come to Canada.

On Monday, Mitacs, the national non-profit that connects graduate researchers with industry, announced that it would fund 100 students from the affected countries to take up four-month research awards at universities across the country.

Law schools at McGill University and the University of Toronto have reopened their window for application. U of T’s law school contacted applicants from the affected countries who had been accepted to U of T but went to the States to offer them a transfer to Toronto. Other schools, such as the University of Alberta and the University of Calgary, have waived application fees.

“These students have worked hard, they’ve applied to U.S. institutions and now they’ve learned they can’t go,” said Dr. Mandigo at Brock, which is offering students from affected countries a $1,000 transition grant. “We wanted to provide alternatives to them; we wanted to make it just a little bit easier.”

Universities are also working on how to help professors and researchers who may be affected. Transfers to Canadian universities are one possibility. According to numbers obtained by The Globe and Mail from Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada, over the last two years, approximately 350 visas were issued to visiting professors and postdoctoral researchers from the seven countries, with most taken up by Iranian citizens.

For Canadian academics, the need to express solidarity was immediate.

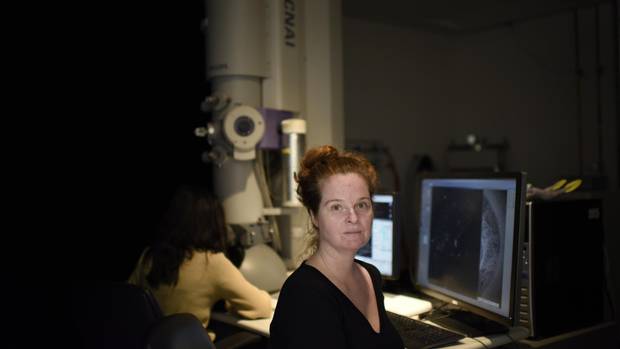

“Science is an international pursuit. You walk into a lab and people are from all over the world. We’re uprooted from our families so our lab becomes our home,” said Eden Fussner-Dupas, a postdoctoral fellow at the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto.

For years, Dr. Fussner-Dupas and an Iranian-born colleague have been working on one of the puzzles of genetics: how genes are silenced. Working with engineers and computer scientists, they designed an electron microscope technique that helped them show that proteins associated with DNA may be responsible. They were planning to present their findings at a conference in the States this spring.

But because her colleague – who wanted to remain anonymous to protect her career – would not be able to attend, Dr. Fussner-Dupas decided she could not go alone.

“If I had to present the paper without her, it would be like presenting without a relative,” she said.

Dr. Fussner-Dupas and her colleague will still submit their research for publication. Missing the conference, however, means that they will not have a chance to meet with top editors from journals such as Nature and Science. For the academic science community, Dr. Fussner-Dupas said, “the damage has been done.”

SIMONA CHIOSE – EDUCATION REPORTER

The Globe and Mail

Published Monday, Feb. 06, 2017 5:39PM EST

Last updated Monday, Feb. 06, 2017 6:38PM EST