A pair of Barren ground caribou are seen in an undated handout photo from the World Wildlife Fund. BOB BOWHAY/HANDOUT

Species at risk in Canada are facing continued population declines and multiple threats that stand in the way of their recovery, a new report has found.

That assessment, delivered on Wednesday by WWF Canada, is drawn from the latest version of the organization’s Living Planet Report, part of a larger effort to track the state of threatened species around the world over time.

The report combines data on 883 vertebrate species that are native to Canada, most of which are not considered at risk. On the whole, the data show that the combined population trends of those species balance out with about half in decline and the other half with increasing populations since 1970.

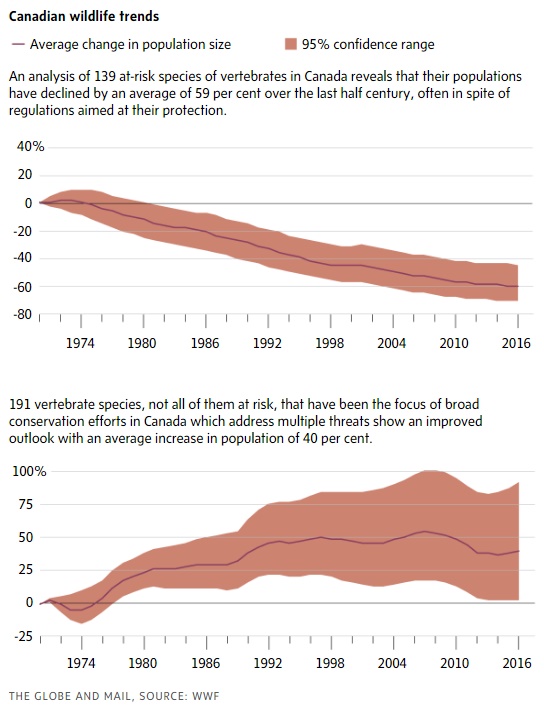

But, when data on 139 species at risk are considered separately, they show an average decline of 59 per cent during that same time period. The report also found that Canadian populations of wildlife, such as the wood turtle or right whale, that are on the “red list” of endangered species maintained by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature, have shrunk by an average of 42 per cent.

The report considered only vertebrate species with more than three years of population size measurements. Of the Canadian species at risk included in the report, two-thirds are birds and fish, while the remaining third are made up of amphibians, reptiles and mammals. Among them are some prime examples of iconic Canadian wildlife that are threatened, such as barren-ground caribou or the Vancouver Island marmot. Invertebrates, including insects, and plant species were not included in the report.

All of the species at risk in the analysis have been assessed by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada, a government-appointed body of scientists and other experts that determines which species should be recommended for protection under federal law. As the results make clear, such a designation alone is not sufficient to stop species decline without more concerted conservation efforts.

James Snider, WWF Canada’s vice-president of science, knowledge and innovation, who led the analysis, said a big part of the problem is that species at risk face multiple threats, including overexploitation, habitat loss, pollution and climate change, among others. On average, they encounter five threats, with combined effects that can be devastating to populations. Regulations aimed at addressing just one threat are therefore unlikely to improve the outlook for any species.

A Vancouver Island marmot is seen in an undated handout photo from the World Wildlife Fund. RYAN TIDMAN/HANDOUT

“We need to take a much more integrated and holistic approach if we’re going to see successful recovery of those species,” Mr. Snider said.

He added that strategies for wildlife recovery should be developed in an equitable way, and with Indigenous participation as a high priority. A range of scientific studies have found that biodiversity fares better on Indigenous lands. The need for more habitat protection can also dovetail with decisions that promote Canada’s response to climate change – for example, by maintaining forest and peat lands that store carbon, or wetlands that provide a buffer against flooding.

One positive result from the analysis showed that for 191 species that benefited from broad measures to improve conservation, population sizes increased by an average of 40 per cent over the past half-century. However, Mr. Snider added, “We have been cautious … since additional factors may also be influencing the trends in abundance for these species.”

The report is issued at a key time for conservation-related decisions in Canada, as the federal government nears the deadline on an international commitment to set aside habitat for protection by the end of 2020 and is considering new targets for the future. The possibility of a federal election in the coming months adds a further layer of uncertainty to the picture. At the same time, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has conservation groups worried about possible moves by the provinces to loosen environmental regulations in the name of economic recovery.

Globally, there has been increasing evidence of the link between species declines and the stacking of detrimental impact. The issue captured global attention last year when officials with the United Nations panel on biodiversity declared that one million species on the planet face some risk of extinction. Many of those species are found in tropical areas where biodiversity is highest.

A North Atlantic right whale is seen in the Bay of Fundy, N.B., in this undated handout photo from the World Wildlife Fund. WAYNE BARRETT & ANNE MACKAY/HANDOUT

Justina Ray, president and senior scientist with the Wildlife Conservation Society Canada, who was not involved in the WWF report, said the analysis makes an important contribution because it draws attention to conservation challenges that are closer to home.

“You could be lulled into some kind of complacency because we have a lot of intact ecosystems and we’re a high-governance country,” Dr. Ray said. “But reports like this make very clear that we have major issues here as well.”

Last year, Dr. Ray co-authored a study published in the journal Conservation Letters that examined how decisions that affect species at risk can be more consequential than they seem because of cumulative effects. For example, a new road or power line running through a stretch of natural landscape may be assessed as producing a modest disturbance for species, but the development that it enables ultimately has a far larger effect.

“We typically don’t regulate smaller changes very well,” said Chris Johnson, a professor of landscape management and conservation at the University of Northern British Columbia. “And we don’t do a good job of summing up all the smaller footprints that we have on these landscapes.”

IVAN SEMENIUK

SCIENCE REPORTER

The Globe and Mail, September 2, 2020