Statscan’s latest release of census data paints a clearer picture of a Canada where single-person households, same-sex marriage, language diversity and bilingualism are on the rise. Gloria Galloway explains the highlights.

More Canadians are opting to live alone as the country’s population ages and as women become better able to foot the household bills by themselves.

Those are the findings of the latest data from the 2016 census, which looks at the number of people who live under the same roof, the types of families Canadians are forming and the range of languages they can speak.

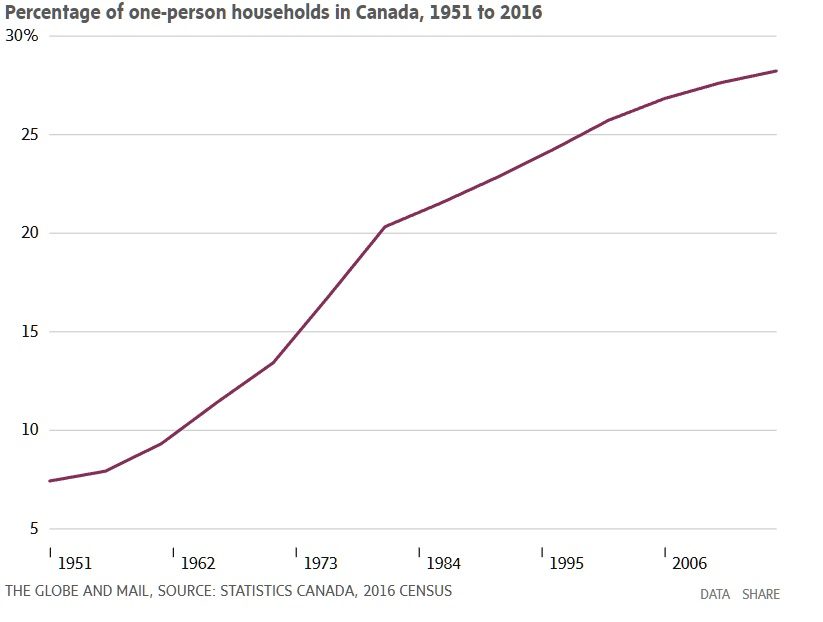

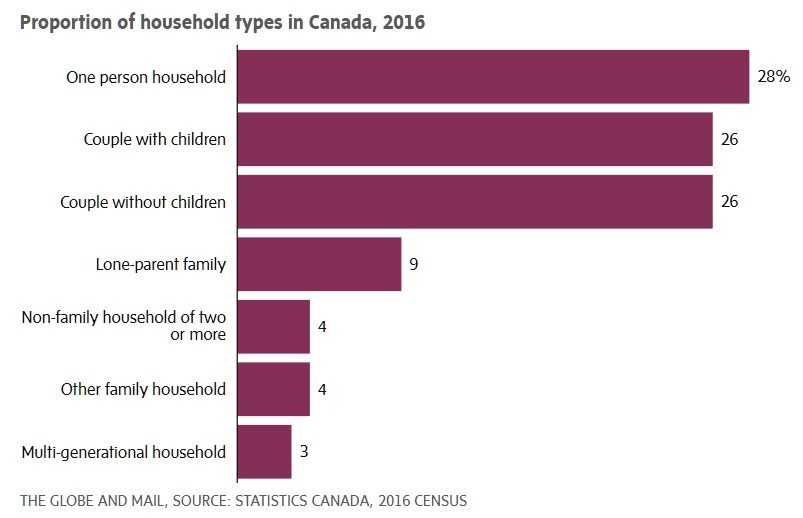

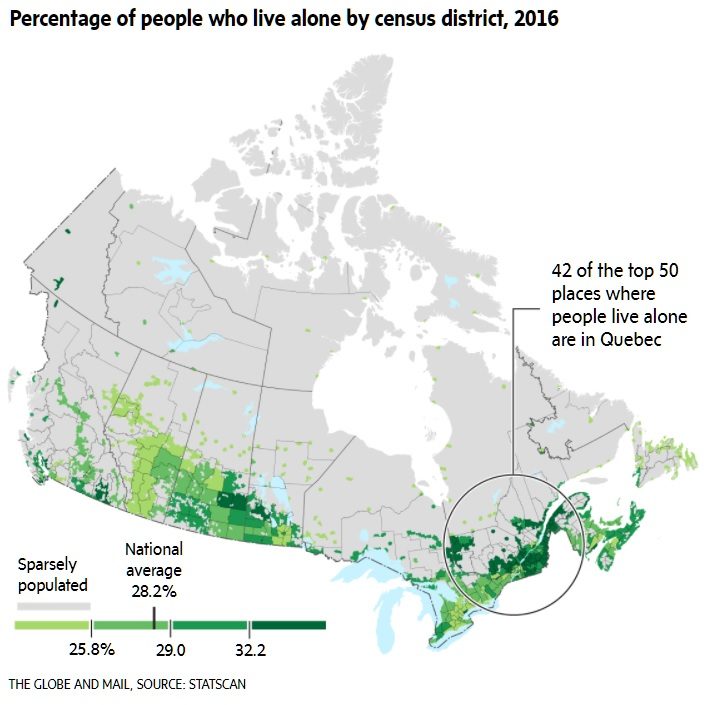

For the first time in the country’s history, the number of one-person households has surpassed all other types of living situations. They accounted for 28.2 per cent of all households last year, more than the percentage of couples with children, couples without children, single-parent families, multiple family households and all other combinations of people living together.

That mirrors trends in the United States and Britain, but is still significantly lower than that in other developed countries. In Germany, for instance, 41.4 per cent of people lived alone in 2015.

But while single living is becoming more common, there are some demographic groups in Canada that are bucking that trend. The proportion of women over the age of 65 who are living alone fell to 33 per cent last year from 38.3 per cent in 2001, while the ranks of those who were married or living common-law increased.

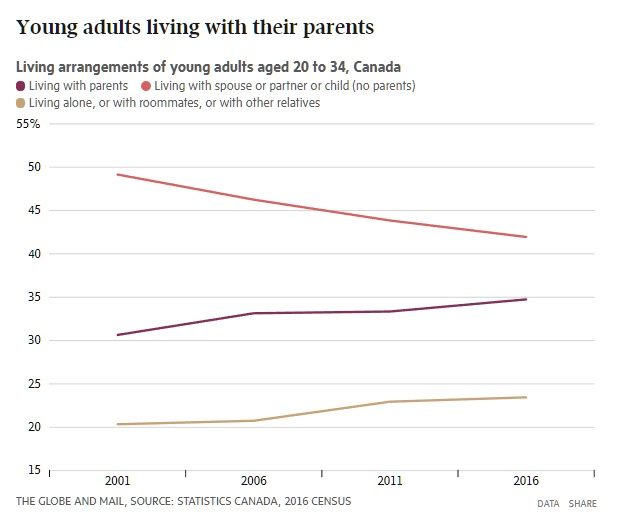

And the number of young adults between the ages of 20 and 34 who are living with at least one parent is also on the rise.

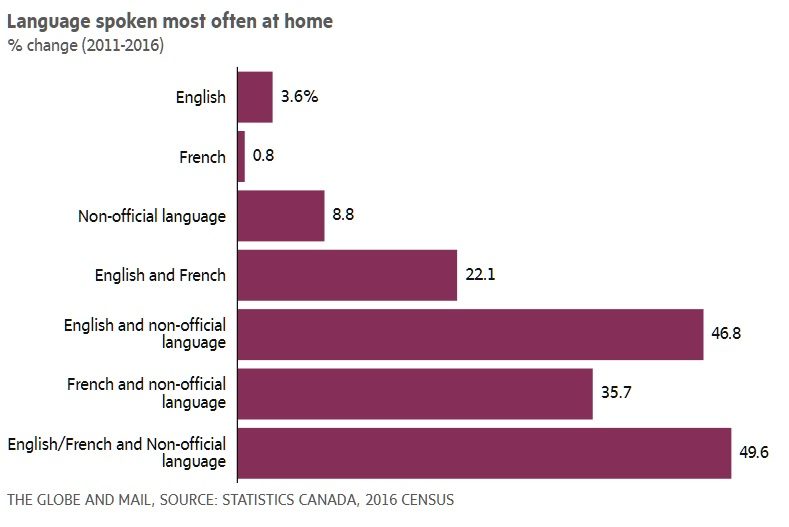

In terms of language, the census finds that Canadians are becoming increasingly diverse. The influx of immigrants has created a country in which increasing numbers of us speak a language other than English or French at home, but the number of Canadians who can speak both of Canada’s official languages is also rising after a decade of levelling off.

Why are so many living alone?

Although it is easy to assume that more people living alone means Canadians are lonely and unhappy, experts say that is not necessarily the case. They key difference between a happy and an unhappy single-person household, they say, is whether the independence is a choice.

Barbara Mitchell, a professor of sociology and gerontology at Simon Fraser University in British Columbia, said much of the trend toward living alone can be attributed to greater individualism and changing gender roles.

“A lot of women now have the economic means to afford to live on their own,” said Dr. Mitchell, and many senior women want to have a home to themselves after a lifetime of taking care of other people, she said.

“A lot of the research seems to suggest that living alone confers a lot of negatives in terms of health outcomes,” Dr. Mitchell said. “But I think it is really dependent upon whether it is a choice or whether it is forced upon you.”

Roderic Beaujot, a professor emeritus of sociology at the University of Western Ontario in London, said innovations such as microwave ovens and the convenience of fast foods have made it easier to maintain a household as a single person. And social media, he said, means single dwellers can stay connected with friends and family.

“So the technology, both to make it possible to live alone and the technology to continue to be an interacting human living alone, is making it less of a negative,” Dr. Beaujot said.

Families, households and marital status

The percentage of one-person households has quadrupled since the middle of the 20th century as the country became increasingly urbanized and large rural families were no longer the norm. In 2016, nearly 14 per cent of all Canadians over the age of 15 lived alone, compared with 1.8 per cent in 1951.

Statistics Canada attributes the trend to an increase of women in the work force, higher separation and divorce rates, and longer life expectancies – seniors are more often single than people in younger age groups.

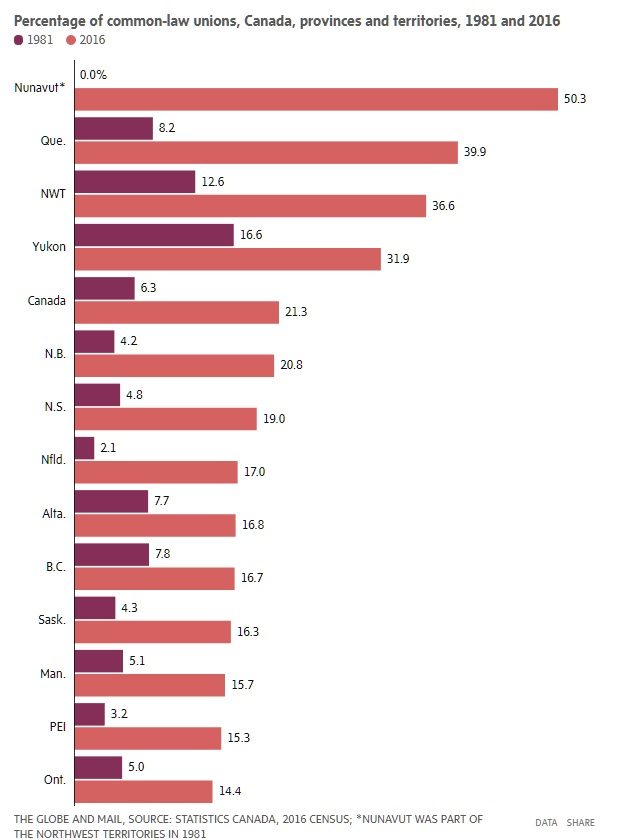

Meanwhile, the family dynamics of Canadians are changing. While married couples still account for the majority of unions, more than a fifth of Canadian couples lived in a common-law situation in 2016 – up from just 6.3 per cent in 1981.

The number of couples without children increased faster between 2011 and 2016 than those with children – a function of an aging population with parents becoming empty-nesters.

And the arrival of large numbers of immigrants from countries where grandparents, parents and children traditionally live in the same home made multigenerational households the fastest growing type of household between 2001 and 2016.

Céline Le Bourdais, the Canada research chair in social statistics and family change at McGill University in Montreal, cautions that the statistics on one-person households can be misleading.

In cases where couples have separated or divorced and share custody of children, Dr. Le Bourdais said, the father or mother who did not have the children on the night before the census was completed would be registered as living alone even though they have their kids with them much of the time. And it is important to remember that the census, in this case, is counting households, not people, she said. Multiperson households, by their nature, account for more individual Canadians.

Like the others, Dr. Le Bourdais said it would be wrong to assume to most people who live alone are poor and lonely. Often, she said, it is just a matter of what a person wants and can be managed financially.

Single-parent families are becoming more frequent and children in those situations are increasingly living with their dads.

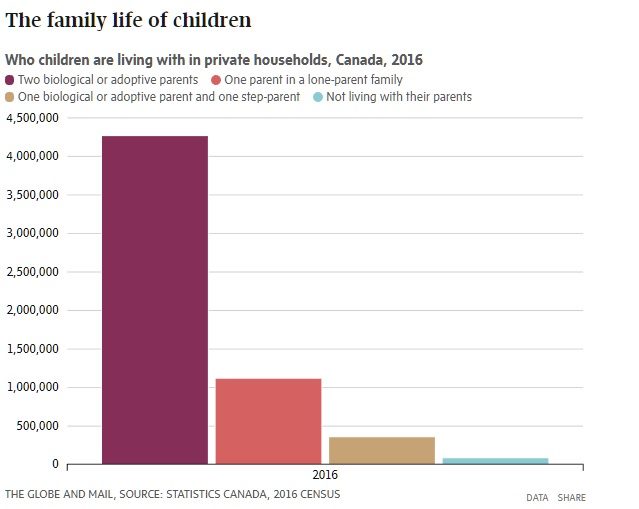

In 2016, more than a million Canadian children – about two in every 10 – lived in a single-parent family.

While the percentage of kids living with a mom or a dad has been increasing for decades, and single-parent moms are still the majority, the proportion of children who were living with their father climbed by 34.5 per cent between 2001 and 2016, while the proportion who were living with their mother increase by just 4.8 per cent.

The number of people who get their own place when they reach their 20s is decreasing and, in 2016, more than a third of Canadians between the ages of 20 and 34 lived with at least one parent.

For years, women have been more eager than men to obtain their independence. In 2016, there were five young men for every four young women who were living under a parental roof. But the gender differences are becoming less pronounced. Between 2001 and 2016, the proportion of young women living with one or both parents rose twice as quickly as the proportion of young men choosing the same. This also means that proportionately fewer young adults have their own families than was the case in previous years. The percentage of young adults living with their own children declined to 25.5 per cent in 2016 from 32.9 per cent in 2001.

Same-sex couples

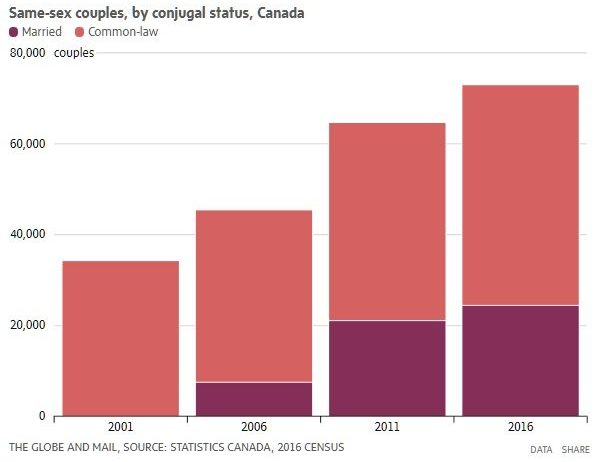

The number of gay and lesbian couples is still just a small fraction of unions in Canada, but their proportion is growing. A decade after same-sex marriage became legal in this country, a third have chosen to tie the knot.

There were 72,880 same-sex couples in Canada in 2016, which accounted for less than 1 per cent of all couples. But, between 2006 and 2016, that increased by 60.7 per cent, compared with an increase of just 9.6 per cent for heterosexual unions.

Although there were more male than female same-sex couples last year, a slightly higher proportion of the female couples were married.

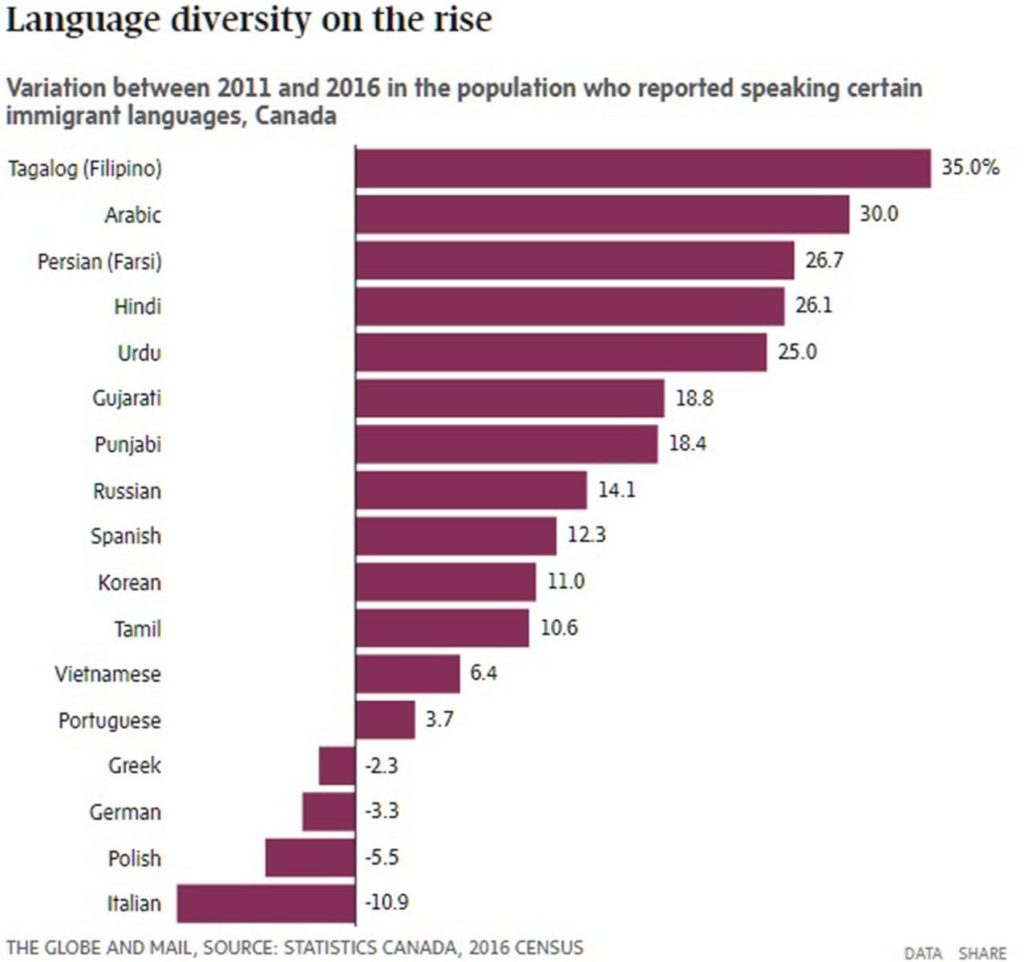

It is still necessary to speak English or French to integrate into Canadian society, but other languages are on the rise – especially those from the Philippines, the Middle East and India.

Meanwhile, the proportion of Canadians who say English or French is their mother tongue dropped to 78.9 per cent in 2016 from 82.4 per cent in 2001.

The overall number of English speakers was up from 2011, while the number of people who said they spoke French at home declined across Canada and in Quebec.

Mandarin and Cantonese remained the most common non-official languages spoken in Canadian homes last year. But, for the second consecutive census period, Tagalog (the language of the Philippines) was the fastest growing with the number of people who speak it rising by 35 per cent between 2011 and 2016. The number of Arabic speakers climbed by 30 per cent during the same period, while Farsi speakers rose by 26.7 per cent, Hindi speakers were up by 26.1 per cent and Urdu speakers were up 25 per cent.

European languages, with the exception of Spanish, were down.

Among Indigenous people in Canada, Cree was the most common language – 83,985 people reported that they spoke Cree in their homes in 2016. That was followed by Inuktitut, Ojibway, Oji-Cree, Dene and Montagnais (Innu).

The number of people who reported that they spoke an Indigenous language at home was higher than the number who said it was their mother tongue, which reflects the growing interest in learning the languages spoken by Indigenous forebears.

Bilingualism grows

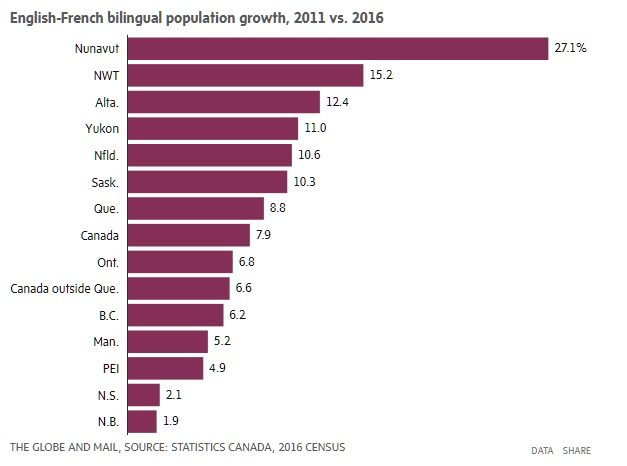

More Canadians say they are bilingual than at any point in Canadian history.

Between 2011 and 2016, the English-French bilingualism rate rose to 18 per cent from 17.5 per cent. That climb occurred after a decade of levelling off.

But bilingual Canadians remain concentrated in Quebec, where 42.6 per cent reported being able to speak both official languages in 2016, and the growth in bilingualism over the past five years largely took place in that province. The majority of bilingual people say French is their mother tongue.