Low water threatens to cut off waterways more often, and less predictably, than ever before – and the alternatives to river shipping are potentially even worse for emissions

In the late summer of 2018, Ben Maelissa, chief executive and part owner of Netherland’s Danser Group, one of Europe’s largest operators of freight river barges, received a series of rather distressed messages from his captains. The water levels in certain parts of the Rhine River had sunk so low that their ships were trapped.

The problem was particularly dire at Kaub, a town about 80 kilometres west of Frankfurt, where the Rhine sweeps past Pfalzgrafenstein Castle, a formidable 14th-century riverside fortress that served as a toll station and routinely blocked ships from moving upriver or downriver until a ransom was paid.

This time, it was the climate – lack of water – that was doing the blocking.

“The situation was terrible at some points,” Mr. Maelissa said. “For two or three weeks, we had to stop sailings on the Rhine. Low water is a normal experience in the Rhine, but the extreme low water in 2018 was rather new. …It cost us a lot of money.”

It cost Germany a lot of money, too, since the Rhine is Europe’s – and one of the world’s – most important commercial waterways. Economists at the Dutch bank ING estimated that the low-water crisis on the Rhine that year shaved as much 0.4 per cent off the GDP of Germany, the world’s fourth-largest economy, as factories faced delays for the essential commodities and supplies needed to keep products moving out the door.

Their penchant for just-in-time barge deliveries left no margin for error, compounding the problem.

The waning Rhine – the water is low again this year – is a sign that climate change is becoming a potentially catastrophic economic issue. While not all the commercial users and custodians of the Rhine believe that climate change was at fault in 2018, many do, and they urge businesses that depend on river shipments to make contingency plans for more frequent periods of drought.

Ditto for the Danube, Europe’s second-longest river, after the Volga, which winds its way from southern Germany through central and eastern Europe to the Black Sea. It, too, has seen bouts of low water in recent years.

“We believe the low water is because of climate change,” said Karin de Schepper, director of Inland Navigation Europe, a Brussels group that promotes the sustainability of water transport in the European Union. “The Rhine needs more water for its ships.”

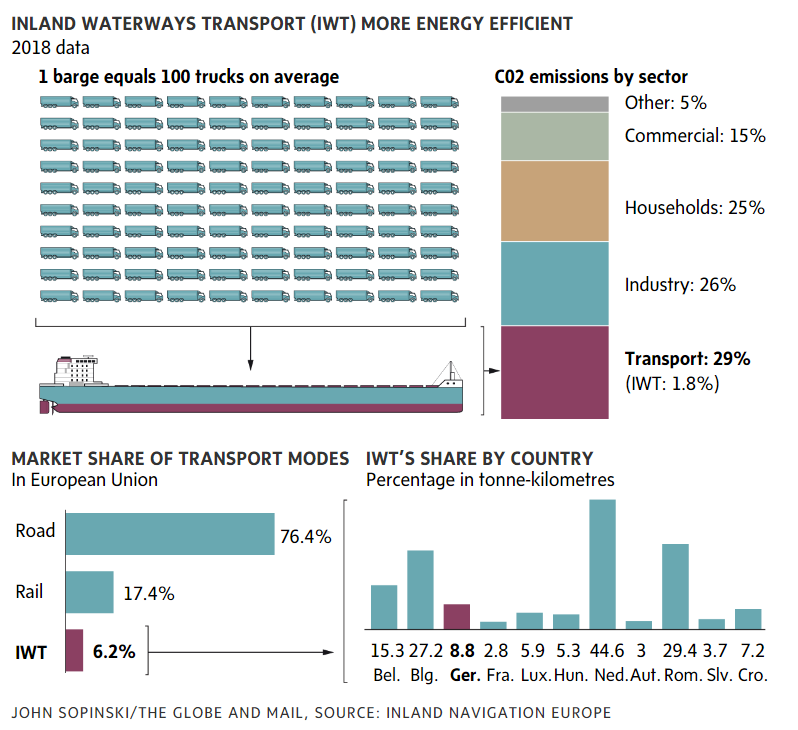

The health of the Rhine is especially important to the EU’s climate goals because barge transport is much more efficient – that is, less energy intensive – than sending the same volume of cargo by train or truck. The Blue Road, a Dutch umbrella group for inland shipping, estimates that a small barge carries as much as 14 tractor-trailer trucks; a medium-sized barge more than 100 trucks; and the largest barges (as long as 185 metres) 240 trucks.

The Rhine extends more than 1,200 kilometres from northern Switzerland, through the industrial heartland of Germany and into the Netherlands, where it empties into the North Sea.

Almost a third of Germany’s coal, iron ore and natural gas are transported along the river, plus a broad range of manufactured goods, from Swiss medicines and cheese to German car parts and machine tools. The Central Commission for Navigation of the Rhine (CCNR), says 600 vessels cross the Dutch-German border on the Rhine every day.

The Rhine is considered a strategic waterway not just in Germany and Europe, but as far away as China. Duisburg, the western German city at the confluence of the Rhine and the Ruhr river, another major German transportation artery, is considered the European terminus of China’s Belt and Road Initiative, China’s global infrastructure network. Dozens of freight trains arrive from, and leave for, China every day from Duisburg.

The Rhine is fed by water runoff from glaciers and melting snow in the Swiss Alps, and by rainwater in its lower stretches. Normally, the combination of the three is enough to keep the mighty river brimming with water – enough to satisfy the needs of cargo and passenger ships and municipal and agricultural use.

But every decade or so, the water levels drop precipitously on the Rhine, also on the Danube, holding up shipping at the bottleneck points – the stretches where water depths are low even when the rivers are running at average depth.

In September, 2003, a severe drought dropped the lower Danube to its lowest level since 1840. Shipping came to a halt and Romania’s nuclear power plant shut for almost a month for lack of water to cool its reactors.

The water levels for much of the last half of 2018 at Kaub reached their lowest level since 2011, perhaps earlier (estimates vary somewhat). Standard container barges need about 2.5 metres of water to travel safely through Kaub with a full load. If the depth drops to 75 centimetres or so, the barges have to lighten their load by about three-quarters to prevent a vessel’s propellers from hitting the river bottom.

According to Energy Intelligence, the water depth at Kaub, near Frankfurt airport, briefly hit a low of 23 centimetres on Oct. 23 that year.

Fuel stocks for airplanes and cars went scarce as tanker skippers idled their engines. Emergency fuel supplies had to be deployed and industrial companies whose factories line the Rhine, such as the German chemicals giant BASF, suddenly had to switch to trains and trucks for crucial supplies. BASF said the temporary move away from barges cost the company €250-million ($389-million). “Road is always huge competition for barges,” said Theresia Hacksteiner, secretary-general of the European Barge Union. “It should be vice-versa.”

The Rhine level recovered somewhat, but remained low until the end of 2018. Mr. Maelissa, of Danser, said that some of his barges could take only 10 per cent to 15 per cent of their maximum load. “We wanted to ensure the boats wouldn’t get stuck,” he said. “Some colleague [skippers] hit the ground.”

The company had to impose a low-water surcharge to make up some of the financial losses. A barge that can only take, say, a 25-per-cent load, has to make four trips to deliver its full cargo.

The Rhine is low this year, too, but not as low as it was two years ago. Early this week, at the Kaub bottleneck, the water was just 90 centimetres deep, less than half the level that barges need to take a full load. Mr. Maelissa was running his eight Rhine barges (he operates more than 80 in other European waterways) at 50-per-cent capacity. Rain was predicted to arrive at the end of the week. If it doesn’t come, the Rhine could face another disaster in the autumn.

While there is some doubt that climate change triggered the 2018 Rhine disaster, and the low water this year, there is no doubt Europe is heating up, suggesting that heightened evaporation and declining snow and glacier cover in the Swiss Alps will boost the low-water incidents in the Rhine, the Danube and elsewhere.

The European Environment Agency says that average temperatures in Europe from 2009 to 2018 were between 1.7 degrees C and 1.8 degrees C higher than preindustrial levels, making that decade the warmest on record. And Europe is warming at almost twice the global rate. Over the same period, near-surface land and ocean temperatures rose between 0.91 degrees C and 0.96 degrees C. Europe is seeing extreme heat waves every two or three years.

This inconvenient truth is not lost on Europe’s river watchers and there is a debate under way in Germany and Netherlands on how to ensure the Rhine can remain open year round as temperatures rise. The options including building a network of new locks and dams that can pour water into the Rhine when its waters recede. That scenario is one endorsed by Martin Brudermuller, CEO of BASF.

But the cost of re-engineering the Rhine would be formidable, and diverting precious water supplies to the Rhine during a drought might come with severe environmental consequences. Inland Navigation Europe would prefer to see gentler efforts that would include launching a new generation of barges that can operate in shallow waters.

Propeller diameters could be reduced, for instance. A more innovative approach would see barges equipped with swing-arm buoyancy tanks on their flanks to raise the hull enough to get a barge through shallow water. Still another option would be the use of lighter materials, such as aluminum, to reduce the weight of barges and hence the draught (the depth of the ship below the water surface).

The effort to find ways to prevent shallow water from crippling Europe’s main commercial waterway has become a top file in Berlin, Brussels and The Hague. Fears about climate change will keep it there, since less use of the Rhine, the Danube and other rivers automatically translates into more use of less-efficient trains and road-clogging trucks. “Waterway transport is crucial to meet Green Deal targets in Europe,” Ms. de Schepper said.

VISUAL GUIDE

How rivers lighten our carbon footprints

The Globe and Mail, September 25, 2020