The Shanghai Creek fire burns in the Yukon on July 30, 2019, triggering evacuation alerts for nearby Keno City and Elsa areas. YUKON PROTECTIVE SERVICES

As summers get drier and warmer, infernos such as those in Alaska and Siberia could become more common – and push traditional firefighting methods beyond their limits.

Unusually aggressive wildfires in the Arctic are releasing waves of greenhouse gases, lasting longer, reaching deeper and burning at higher latitudes than in previous years, and experts say this is fuelled by climate change.

Canada’s territories have been spared the worst of this year’s fire season, but alarming wildfires in Alaska and Siberia underscore how vulnerable this country’s Far North is to a warming climate. Fires in those areas, where the landscape is made up of peat and permafrost, are especially bad for the environment.

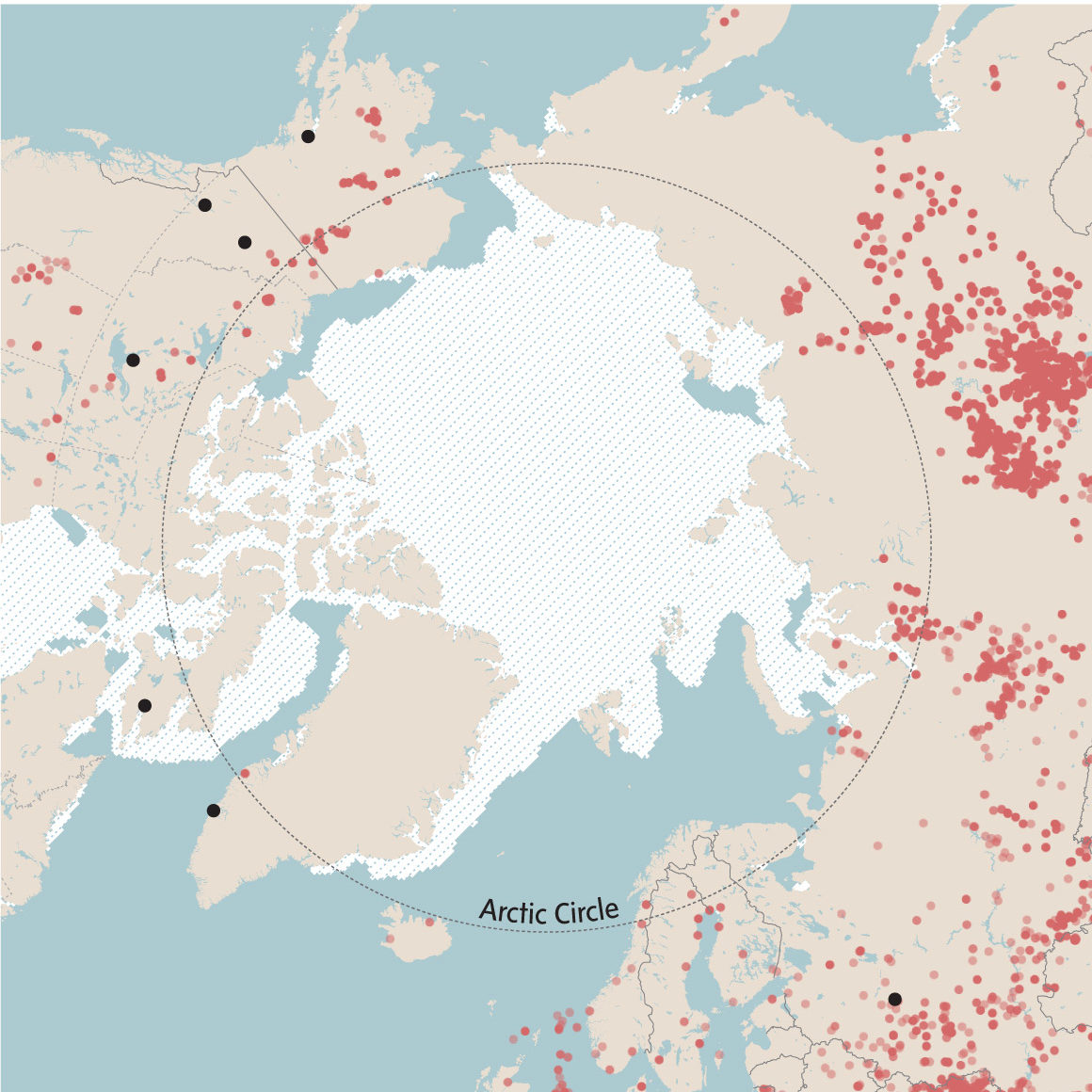

The fires follow an extended stretch of warm weather in Alaska and Siberia. The European Union’s Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service estimated fires inside the Arctic Circle in June emitted more carbon dioxide – 50 megatonnes – than the previous eight Junes combined. Experts say the volume of other gases, such as methane, is unknown.

Monster fires at high latitudes are especially concerning for fire specialists such as Mike Flannigan, a professor at the University of Alberta’s renewable resources department and director of the Western Partnership for Wildland Fire Science. Peat is organic material that is at least 40 centimetres thick and acts as a reservoir for carbon dioxide that has been building up for thousands of years. “They’ve always burned, but now there’s more areas burning and they are burning deeper,” he said. “More fire means more greenhouse gases, means more warming, which then means even more fire.”

Smoke from the fires has been visible on satellite images.

Yukon’s Keno City – a village south of the Arctic Circle in Canada’s Far North – was under an evacuation alert due to a nearby wildfire until earlier this week. Joseph Volf, a long-time Keno City summer resident, says he has noticed a change in the way fires behave in recent years. “Climate change makes it worse,” said Mr. Volf, who curates a local mining museum. “The last 15 years up here have been incredibly dry. We’ve had more like the southern summers.”

Emergency officials acknowledge they must adjust their strategy to the changing conditions.

Yukon’s acting director of wildland fire management, Mike Smith, said just fighting the fires will not be enough to protect northern communities as blazes multiply and intensify.

The territorial government is emphasizing preparation: establishing evacuation plans, considering more fuel breaks, evaluating more prescribed burns around communities and investing in fire science.

“We are already at the point where we are stretched too thin,” Mr. Smith said. “We know there are going to be, and continue to be, large fires that we can’t effectively manage.”

So far this year, 108 fires have swept Yukon, which is in line with its 10-year average. The fires, however, have already burned up 249,000 hectares – about 50 per cent more area than in the average year. In contrast, the situation in the Northwest Territories is well below average, with 132 fires so far burning about 75,000 hectares, according to figures from the territorial government. Natural Resources Canada says the 10-year average for the Northwest Territories is nearly 690,000 hectares. The department does not report statistics for Nunavut.

Year-to-year, the situation can fluctuate wildly. In 2017, Yukon had 115 fires that burned up 471,000 hectares – the largest area in a decade. Last year was comparably mild, with 67 fires covering 86,000 hectares.

The danger of more devastating wildfires in the north is amplified by its remoteness.“We don’t have infrastructure,” Bob McLeod, the Premier of the Northwest Territories, said in an interview. “It is a lot easier to fight a fire if you can just drive right up to it.”

The global land temperature in June was the highest in at least 140 years, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Nine of the Earth’s warmest Junes have occurred since 2010, the U.S. agency said in its monthly report.

Alaska recorded its second-warmest June this year since it began tracking temperatures in 1925. Northern Russia also set new heat records, NOAA said. The heatwave continued into July. Further, the Arctic’s surface air temperatures are warming at twice the rate of the rest of the planet, according to NOAA’s 2018 Arctic report. Arctic temperatures between 2014 and 2018 exceeded all records since 1900, the agency said in the report.

Alaska and Siberia this year have experienced an extended high-pressure system, which brings warm and dry weather, Prof. Flannigan said. The jet stream determines where high and low pressure systems go and how long they linger. The phenomenon is powered by the difference between Arctic and equatorial temperatures, so as climate change narrows the differential, the jet streams slow, Prof. Flannigan said.

While scientists are familiar with how Arctic fires affect peat and carbon dioxide, they are less informed about permafrost and methane emissions.

Thawing permafrost releases methane, which is especially effective at trapping heat. Scientists do not know how much methane is being released, Prof. Flannigan said. “It could be quite significant,” he said. “It is uncharted territory.”

Further, scientists’ understanding of the relationship between sea-ice cover, global warming and wildfires is shaky, according to Mark Serreze, the director of the National Snow and Ice Data Center at the University of Colorado. “There’s a lot we know about what’s happening to the Arctic,” he said. “But there’s a lot we still don’t have quite pinned down.”

Sea-ice cover for July 30 was at a record low, Prof. Serreze said on Tuesday. Soot darkens the surface of sea ice, which hastens melting. But scientists are unsure whether this year’s wildfires are a big factor in this year’s melt.

“I suspect that it is playing a role,” he said. “How strong is it right now? I don’t know.”

CARRIE TAIT

The Globe and Mail, August 1, 2019