Canada is among the countries that are far off track from delivering on their emissions-reduction pledges, as global temperatures are set to rise alarmingly by at least 2.4 C above preindustrial levels by the end of the century, according to an international analysis.

Despite new national commitments announced during the first week of the United Nations climate conference in Glasgow, the world is slated to blow past the Paris Agreement goal of limiting warming to 1.5 degrees – the threshold many scientists say would avert the most devastating effects of climate change.

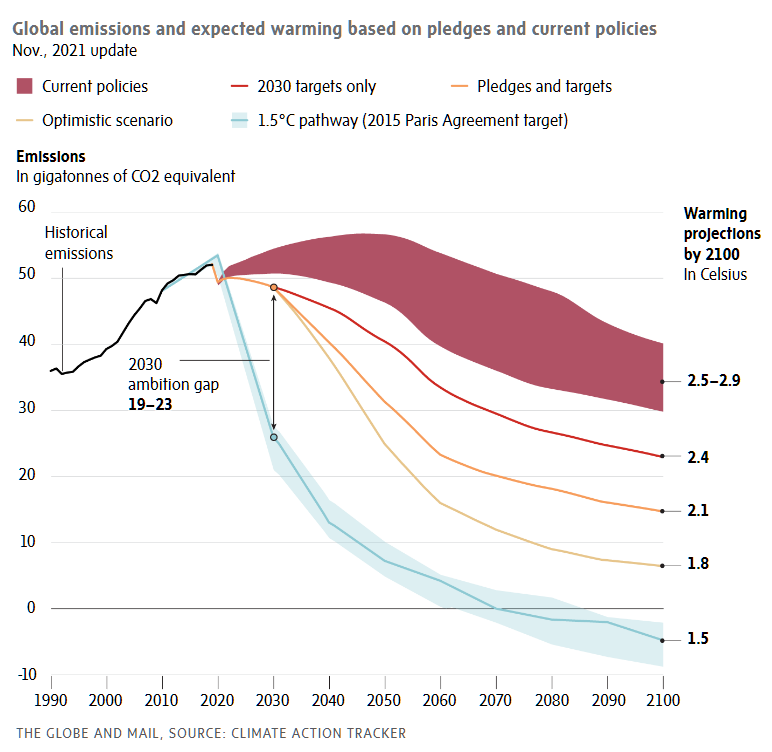

The Climate Action Tracker (CAT) analysis, presented at the COP26 summit on Tuesday, says global greenhouse-gas emissions in 2030 will still be roughly twice as high as necessary to meet the Paris goal. It warns that even in the best-case scenario, in which every government fully implemented all of their emissions-reduction targets, the Earth will still warm by 1.8 degrees.

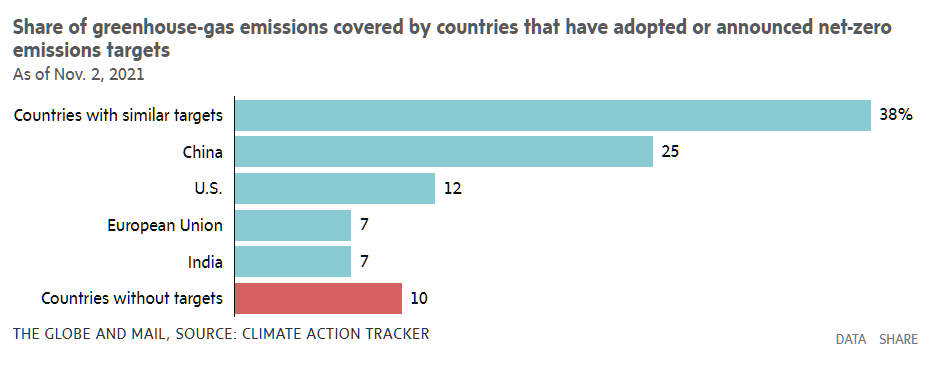

More than 140 governments, including Canada’s, have announced net-zero commitments. Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi surprised world leaders last week when he said his country will aim to reach a net-zero emissions target by 2070.

But such headline-making pledges risk creating false hope and threaten to overshadow widespread government inaction, according to representatives from the two groups behind the CAT analysis.

“Glasgow is meant to keep the Paris Agreement’s 1.5-degree limit in sight, but the 2030 emissions gap is still so huge that we can’t really see that being possible at the present,” Bill Hare, CEO of Berlin-based non-profit Climate Analytics, said via video link at a press conference in Glasgow.

“It’s all very well for leaders and governments to claim they have a net-zero target, but if they don’t have plans for how to get there, and if their 2030 targets are not aligned with net zero, then frankly these net-zero targets are just paying lip service to real climate action.”

For that reason, he said, COP26 has “a very big credibility gap.”

Niklas Hohne, founding partner of the other CAT research group, NewClimate Institute, said not a single country has short-term policies in place to put itself on the path to meeting its own net-zero targets. (Net zero means a country either emits no greenhouse-gas emissions or offsets its emissions by employing carbon-capture technologies or through natural climate solutions, such as tree-planting.)

“This COP has only moved a small step forward,” he said.

Canada initially committed to reducing emissions to 30 per cent below 2005 levels by 2030, but earlier this year, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau upped the target to at least 40 per cent. Mr. Trudeau’s Liberal government has also passed legislation enshrining in law Ottawa’s emissions-reduction targets, including a commitment to reach net zero by 2050.

The CAT report said that while passing a net-zero accountability act is a positive step for Canada, the country’s targets still fall short of 1.5-degree compatibility.

“Canada has updated its [Nationally Determined Contributions] but needs to focus on implementing the policies to achieve it as it is currently far off track,” the report says, referring to Canada’s emissions-reduction targets, which are known under the 2015 Paris Agreement as NDCs.

“It continues to fund fossil-fuel pipelines, exceeding the capacity need. Raising transport emissions are also a concern.” The CAT report deemed Canada’s contribution to international climate finance, aimed at supporting developing countries as they work to mitigate and adapt to climate change, as “highly insufficient.”

In an e-mail to The Globe and Mail, a spokesperson for federal Environment Minister Steven Guilbeault defended Ottawa’s emissions-reduction plans as “detailed and concrete” and said recent commitments will help the country meet its 2030 target.

“With new 2030 mitigation targets this year from the U.S., Japan and Canada, combined with strong action from the E.U. and U.K., countries accounting for more than half of the world’s economy have now committed to the pace of emission reductions required globally to limit warming to 1.5 degrees,” spokesperson Joanna Sivasankaran said.

Last week, Mr. Trudeau told world leaders at the summit that Ottawa will impose emissions caps on the oil-and-gas industry, in a bid to meet the country’s climate goals. The federal government has also committed to reducing methane emissions, which account for about 13 per cent of Canada’s total greenhouse-gas emissions, by at least 75 per cent below 2012 levels by 2030.

Maria Jose de Villafranca Casas, a climate policy analyst at the NewClimate Institute, said at the press conference in Glasgow that many countries still rely on coal and gas. “These are two things that need to be dealt with in the next decade, if we’re going to stay on track for 1.5 degrees,” she said.

Last week at COP26, more than 40 countries agreed to transition away from coal power, but the global pact was compromised by the decisions of the world’s biggest emitters not to sign on.

The host British government made it a primary goal of the conference to “consign to history” the fuel currently responsible for about 30 per cent of the world’s carbon emissions, and succeeded in getting some coal-friendly or coal-reliant countries to join the agreement. But the United States, China and India – which together account for roughly 70 per cent of the world’s coal consumption – were among those that did not sign on.

Also Tuesday, the United Nations Environment Programme issued an addendum to its 2021 Emissions Gap report, which was released in late October and predicted a global temperature rise of 2.7 degrees by the end of the century.

That report, which is partly based on CAT analysis conducted ahead of COP26, was based on commitments made before Aug. 31. The addendum takes into account the impact of new or updated emissions-reduction pledges made since the cut-off date, including those announced in Glasgow.

“These estimates remain very similar to the estimates published in the Emissions Gap report 2021, due to limited changes to 2030 emissions,” UNEP said in the addendum. “Even considering the recent updated pledges for 2030, annual global greenhouse-gas emissions would need to be roughly halved by 2030 to become consistent with a 1.5 degrees least-cost pathway.”

The CAT and UNEP forecasts are in line with a Nov. 4 statement from International Energy Agency head Fatih Birol, who said pledges made in Glasgow last week would put the Earth on track for 1.8 degrees of global warming, if fully implemented.

Speaking in Glasgow on Tuesday, COP26 president Alok Sharma acknowledged that several reports have come to similar conclusions regarding the pace of global warming. “There has been some progress but clearly not enough,” he said.

He added that before the Paris Agreement in 2015, analysts said the world was heading toward 6 degrees of global warming; that fell below 4 degrees after Paris and is now down to about 2 degrees.

“But of course that isn’t good enough,” he said. “What we’ve always said is that we want, at this COP, to be able to say with credibility that we are keeping 1.5 degrees alive, 1.5 within reach. And that is what we are going to be working towards over the coming days.”

KATHRYN BLAZE BAUM

ENVIRONMENT REPORTER

The Globe and Mail, November 9, 2021