Canada’s latest gross domestic product numbers show an economy that ended 2016 on a roll, topping even the most optimistic expectations. But the one weakness it still can’t shake – moribund business investment – remains a nagging threat to economic growth in 2017 and beyond.

Statistics Canada reported that real gross domestic product grew at an annualized pace of 2.6 per cent in the fourth quarter, beating the consensus estimate among economists of 2 per cent, and far above the Bank of Canada’s most recent estimate (published in January) of 1.5 per cent. The growth was propelled by solid exports of both goods and services, strong household consumption and a brisk pace of residential construction and renovation.

It was an encouraging follow-up to the strong third quarter, which Statscan revised upward, to 3.8-per-cent growth from the originally reported 3.5 per cent. While the third quarter was an entirely predictable bounce-back from the temporary slowdown in the second quarter, largely related to the Alberta wildfires, economists had thought the fourth quarter would see a return to the more sluggish growth that has typified the Canadian economy in the wake of the late-2014 oil shock.

They were pleasantly surprised.

“Canadian real GDP ended 2016 in surprisingly healthy shape,” Bank of Montreal chief economist Douglas Porter said, as the bank raised its 2017 growth forecast to 2.3 per cent from 2 per cent in the wake of the GDP report. “The evidence continues to mount that the growth landscape is shifting for the better.”

For December, seasonally adjusted real GDP growth came in at a solid 0.3 per cent month over month, following up on November’s 0.5 per cent – another upward revision, from Statscan’s originally reported 0.4 per cent. The growth was led by strength in construction, manufacturing and wholesale trade, although retail trade took a step back after brisk sales earlier in the quarter.

GDP for all of 2016 was up 1.4 per cent from the prior year – a far from spectacular pace, but it did exceed 2015’s even more lacklustre 0.9-per-cent growth. Most economists expect growth of 2 per cent or more in 2017, as the lingering damage from the oil shock continues to fade, and exports benefit from the improving U.S. and global economies.

The stronger-than-expected growth will raise new questions about the Bank of Canada’s decidedly cautious stance on future interest-rate increases, as the economy outperforms its expectations. The central bank has stressed the divergence between the strong economic conditions in the United States, where interest rates are on the rise, and Canada’s comparatively weak economic state. Yet Statistics Canada noted that Canada’s fourth-quarter growth was well ahead of the U.S. pace of 1.9 per cent.

“Over the past four quarters, Canadian GDP has risen 1.9 per cent year over year. Over the same period, U.S. GDP was up – wait for it – 1.9 per cent year over year,” Mr. Porter wrote in a research note. “Is the ‘divergence’ between the U.S. and Canada really so large any more?”

However, one of the Bank of Canada’s biggest concerns – the continued lack of business investment, which has been the bane of the Canadian economy ever since the 2014 oil shock sucked the life out of energy-sector spending – remains a disturbing fly in Canada’s economic ointment.

Business gross fixed capital formation slumped 8.2 per cent on an annualized basis in the fourth quarter, marking the ninth consecutive quarter that the gauge of business spending declined. Investment in machinery and equipment – a key ingredient for business expansion and productivity growth – fell nearly 11 per cent annualized.

Falling business investment has a direct effect on GDP growth, as it subtracts from a key source of spending and economic activity. But as the investment slump has continued to drag on, a less direct but more profound concern is arising: that the economy is being starved of the tools and productive capacity it will need for future growth.

Craig Alexander, chief economist at the Conference Board of Canada, noted that machinery and equipment investment in the past several quarters hasn’t even kept pace with the rate of depreciation on existing machinery and equipment. “The capital stock in the economy is declining,” he said.

“If you’re not investing in capital, it seriously constrains your long-term growth potential.”

Earlier this week, Statscan’s annual survey of business-spending intentions showed that private-sector businesses plan to reduce their capital spending by 1.6 per cent this year, their third straight decline. This despite rising corporate profits (up 13 per cent year over year in the fourth quarter), and evidence that some non-resource export sectors are already running close to full capacity.

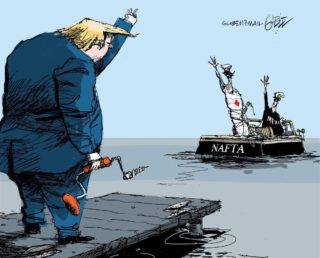

The Bank of Canada has expressed concern that Canada has already lost export growth opportunities because of a loss of capacity to meet new demand. But with fresh uncertainties arising from new U.S. President Donald Trump’s desire to renegotiate trade deals and promote made-in-the-U.S.A. production, companies already reluctant to invest have another strong reason to sit on their wallets again this year.

“I don’t know if I would be willing to invest if I don’t know the rules of the game,” Mr. Alexander said. “But if we don’t change the path we’re on, our potential for growth is going to fall.”

DAVID PARKINSON – ECONOMICS REPORTER

The Globe and Mail

Published Thursday, Mar. 02, 2017 8:39AM EST

Last updated Thursday, Mar. 02, 2017 6:26PM EST