In one of her high-school math classes of 18 students this semester, teacher Karen Ebanks has time to glance over shoulders, guide stragglers back onto the path of understanding fractions, lead them to comprehending equations and, in some cases, help shepherd teenagers to graduation.

With her other classes of 28 and 30 students, she feels pressed for time. And if the classes were to expand further – as the Ontario government is proposing – she is nervous that the numbers would start to work against her.

“I would not have the time to work at that level of detail with each student in a larger class,” said Ms. Ebanks, a teacher at St. Elizabeth Catholic High School in Thornhill. “If these class averages increase and I’m dealing with around 40, instead of walking around and helping with math, I expect to be walking around and doing crowd control.”

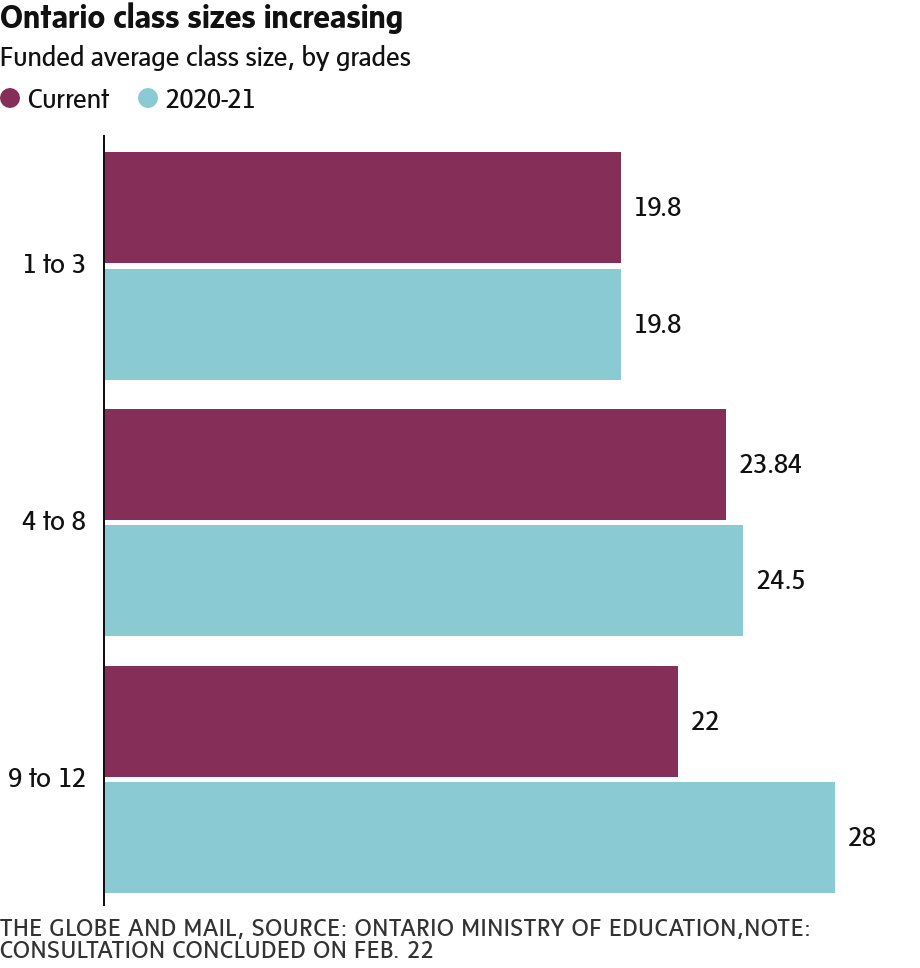

Education Minister Lisa Thompson recently announced average class sizes in high school would increase to 28 students from 22, at one point saying that it would make students more resilient and better prepare them for university and work.

Ontario’s class size increases, which will lead to a loss of teaching positions, come as the government tries to trim a deficit it pegs at $11.7-billion this year. Ms. Thompson has said Ontario’s high schools have one of the lowest class-size averages in the country and the change would align the province with others.

A survey of several provinces showed that British Columbia and Alberta have similar averages to Ontario. Nova Scotia has a “soft” cap of 30 students in Grades 10 to 12, but the flexibility to add two students. Provincial class-size averages are not available. Quebec, meanwhile, has a class-size average of 30 students, but that’s for “regular groups” of students, as noted in an Ontario Ministry of Education document. Quebec has “significantly lower” class-size requirements for students who, for example, may be economically disadvantaged or have special education needs, the document stated.

Research on the effects of reducing class sizes has been concentrated in the primary grades because that’s where governments have devoted most of their attention. One study from the 1980s showed that reducing class sizes in the early years improved academic achievement for young students, especially those from less advantaged backgrounds. Other research has shown that while it has helped improve achievement slightly, the key to quality education is also training teachers to deliver a high-quality curriculum.

Thomas Dee, a Barnett Family professor of education at Stanford University, argued it’s equally beneficial to lower class sizes in the later grades, because it improves certain skills, such as students’ motivation to learn and their engagement in lessons, all of which leads to graduation.

Prof. Dee and his colleague researched the effects of class sizes in the middle-school years, and found that exposure to smaller classes in Grade 8 led to improvements in student engagement that were still detectable, though smaller, two years later. He acknowledged it was an expensive venture, but he said his research found “there’s still quite a reasonable and positive return on those investments.”

Ontario’s move to increase class-size averages, while it would save money on teachers, “I would expect that it would lead to some skill reduction among students as well as reductions in their motivation and engagement that would ultimately translate to poorer labour market outcomes in adulthood,” Prof. Dee said.

“That’s a pretty substantial cost to pay,” he added.

The Ministry of Education said in a recent memo that an estimated 3,475 teaching positions will be lost in the province through attrition over the next four years because of changes to the average class sizes in some elementary grades and in high schools. The government estimated that it would save $851-million over four years.

Harvey Bischof, president of the Ontario Secondary School Teachers’ Federation, warned that the cost to student achievement would be greater.

Ontario’s trend to lower class sizes, mostly done through teacher bargaining, has led to improved graduation rates, he said.

“There’s no world in which the classroom experience is improved for students by increasing the average by six, which will result in increasing some classes up to 40 and 45,” Mr. Bischof said.

Paul Bennett, an education consultant based in Halifax, said research shows smaller classes have not yielded substantial gains in student achievement and what should be taken into consideration is the composition of larger classrooms, where a growing number of students come with unique learning needs.

Class size does not matter “in and of itself,” he said, “but in conjunction with the aggregation of other challenges teachers face, it compounds the difficulty of teaching high school.”

Ms. Ebanks, who has been teaching for almost two decades, said her largest class over her career had 33 students, which she described as “extremely challenging.”

In her Grade 11 class of 18 this semester – one of her three math classes – she has, among others, several students who require accommodations and two students who are a math credit shy of graduation. She said she has time to focus on individual needs in a smaller group and work one-on-one with students to help get them where they need to be.

“I can do that in a class of 18. I can give that kid the attention he needs,” she said. “Where in a class of 33, sadly a lot of those students will feel lost in the crowd because I don’t have that kind of time to personally check in on every single one of them.”

CAROLINE ALPHONSO

EDUCATION REPORTER

The Globe and Mail, April 18, 2019