Despite fears that students would balk at courses held primarily online, enrolment at Canadian universities rose slightly in the fall term driven mainly by an increase in part-time students.

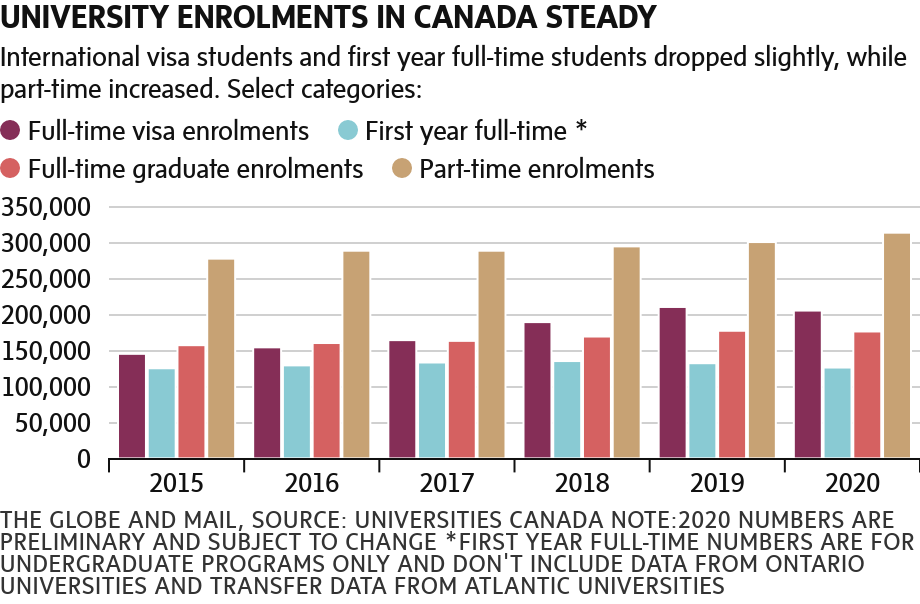

But the national data gloss over smaller, significant trends. First-year enrolment appears to be down and the number of graduate students and international students fell after years of steady growth, which could have an impact that extends over several years.

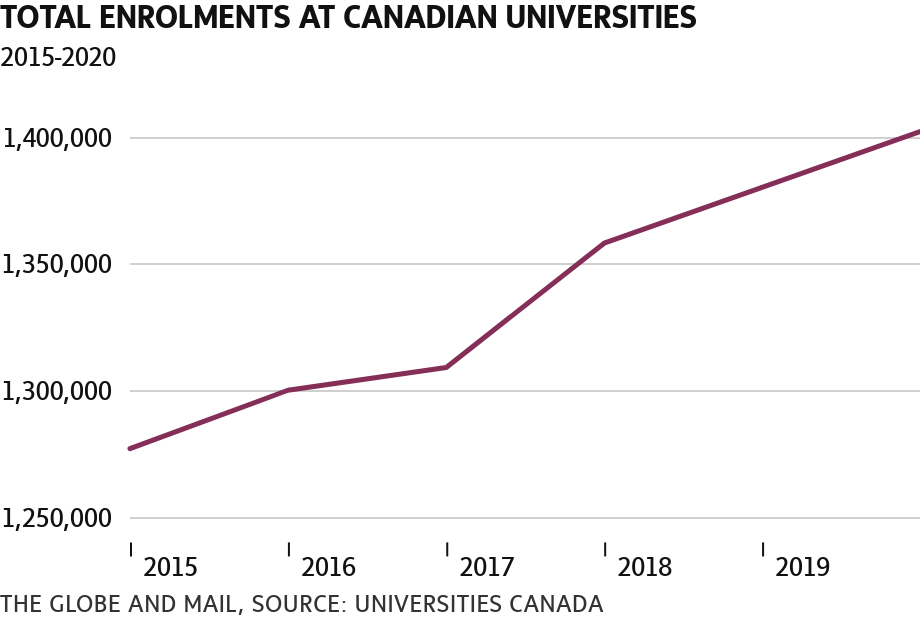

Data from nearly 100 Canadian universities show total enrolments rose by a little more than 1.5 per cent across the country, from 1.38 million students in the fall of 2019 to 1.4 million in the fall of 2020, according to a preliminary survey from Universities Canada, a national umbrella group. The figures are based on data supplied by its members in their annual fall enrolment survey.

Relatively stable enrolment is a promising sign for a sector that feared pandemic-induced drops of 10 per cent or more, which would likely have forced budget cuts.

“In the spring, people were very worried about a significant drop-off,” said Paul Davidson, president of Universities Canada. “Over all, enrolment appears to be up slightly, and that’s really good news.”

Part-time enrolments had a big jump, as people took advantage of the flexibility of online learning, but there were fewer international students, which has a disproportionate impact on postsecondary funding in Canada.

First-year enrolment dropped by nearly 5 per cent across much of the country (although data from Ontario universities were not included in this measure), suggesting that at least some prospective students were put off by the changes to campus life brought on by the pandemic. Mr. Davidson said it’s unclear whether all those students will eventually return. Some may have taken a gap year and will enrol in future. Others may move on from the possibility of university entirely, he said.

A year from now, it’s possible institutions will be dealing with a kind of double cohort, as a bulge of applicants tries to enter at the same time. That could create problems of its own because of limits on spaces and provincial funding. Also, the smaller 2020 cohort will mean reduced income for institutions over its three or four years of study. Still, the situation is less severe than in the United States, where first-year enrolment dropped 16 per cent this fall.

But it’s not the same everywhere. Institutions with prestigious brands and those in major cities tended to fare well. The University of Waterloo, for example, had a 16-per-cent increase in new admissions, Dalhousie’s full-time enrolments increased 3.8 per cent, the University of Calgary increased international enrolments by 8.4 per cent, McGill saw domestic enrolment climb 4.4 per cent and the University of Manitoba had an overall increase of 2.4 per cent.

Smaller schools outside the big urban centres were more likely to see enrolment drop, Mr. Davidson said. In Atlantic Canada, which publishes data for all its institutions in the fall, full-time enrolments were down slightly, at 1.3 per cent, but part-time enrolment was up nearly 20 per cent. Acadia, St. Thomas and St. Francis-Xavier are among those that had small drops among full-time students.

Cape Breton University, which increased its international student population to nearly two-thirds of the student body, saw part-time student numbers jump, but full-time enrolment drop by more than 25 per cent.

Bryn de Chastelain, a fourth-year student at Saint Mary’s University in Halifax and chair of the Canadian Alliance of Student Associations, said students seem to have decided to stay in school through the pandemic. With high unemployment and travel nearly impossible, there weren’t many better options, he said.

“The reality of deferring for a year and trying again next September, we had no way of knowing if the situation was going to be much better,” Mr. de Chastelain said.

The strength of Canadian enrolments may have been affected by significant funding boosts from the federal government. In April, the government announced it was doubling grants and expanding loan eligibility at an estimated cost of $1.9-billion over two years. It also provided income support over the summer through the Canada Emergency Student Benefit.

The number of graduate students at Canadian universities fell for the first time in six years. Some had thought that a difficult job market would have encouraged more students to pursue graduate work, but that proved not to be the case.

Part-time enrolments, which grew by nearly 4.5 per cent, were a particular success at many schools. At Memorial University in Newfoundland, the enrolment office e-mailed students who were halfway to a degree but had been out of school for a year or more. Within a day, dozens had responded, often replying with explanations for not completing their degree, university registrar Tom Nault said. In some cases it was illness or finances that got in the way, or they’d started a family, or left for work in the oil sands only to have the job disappear.

The university said more than 100 decided to return, often as part-time students, which contributed to what it described as its largest annual growth since 2003.

JOE FRIESEN

POSTSECONDARY EDUCATION REPORTER

The Globe and Mail, November 24, 2020