Canadians can expect to spend more than $350,000 to raise a child from birth to the age of 17, according to new estimates by Statistics Canada. And that figure climbs by a further 29 per cent if parents continue to support the child through postsecondary studies until the age of 22, the data show.

The study, released last Friday, is the first “nationally representative” estimate in more than a decade of how much Canadians spend on children, the agency said. It is also a rare effort to quantify child-rearing costs beyond the age of majority, as more young adults take longer to strike out on their own.

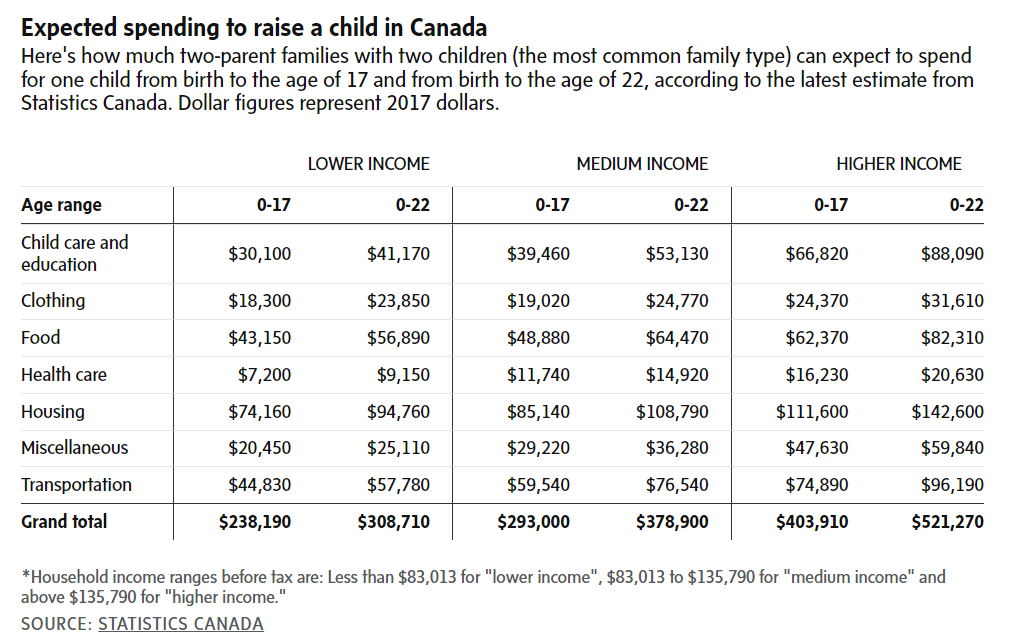

Using data on household spending collected between 2014 and 2017, the report estimates that a medium-income family with two parents and two children would spend an average of $293,000 a child from birth until 17 in 2017 dollars. In today’s dollars, that amount is equivalent to just over $356,000, or roughly $1,745 a month.

The calculations represent an estimate of how much Canadian families typically spend on children. They do not seek to quantify how much parents must spend per child to achieve a minimum standard of living.

The study, which was based on methodology the United States Department of Agriculture uses for similar reports, found that spending per child varies based on variables, including household income, whether there are one or two parents in the family, the number of children in the family and where the family lives.

Among households with two parents and two children, the most common family type in Canada, the average spending to raise a child to 17 is around $404,000 in 2017 dollars (just over $490,000 in today’s dollars) for higher-earning families. That’s nearly 70 per cent more than what the report estimates lower-income families would spend. (The study defines higher-income families as having a household income above $135,790 in 2016. Lower-income families are those with incomes below $83,013 in that year.)

Spending on child-rearing included food, clothing, transportation and health care, as well as housing-related expenditures, which Statscan estimated as the cost of an additional bedroom in the home.

Across income groups, Statscan researchers found that expected spending climbs by around 29 per cent when parents support the child until 22. The increase reflects both the cost of postsecondary education and prolonged spending for other child-related needs. Recent data show 90 per cent of young adults 18 and 19 are living at home with their parents, and 68 per cent of those 20 to 24 are still doing so.

Also, in a finding that might reflect savings from hand-me-down clothes and other cost reductions from having siblings, the study also estimated that spending per child is notably lower for households with a larger number of children. For example, two parents with one child are expected to spend up to 38 per cent more compared with what families with two children are likely to spend per child.

Another source of notable differences is geography. Expenditures for families in the Prairies and British Columbia are up to 15 per cent higher per child compared with those of parents in Atlantic Canada. Families in Ontario and Quebec spent up to nine per cent more compared with parents in the Eastern provinces.

The higher spending levels in the West may be linked to steeper housing-related costs, the authors noted. The report relies on household spending data up until 2017, which predates steep increases in home and rental prices that have since occurred in much of Ontario and parts of Atlantic Canada, as well as B.C.

ERICA ALINI

The Globe and Mail, October 2, 2023