Fentanyl has become the leading cause of opioid deaths in Ontario for the first time since Canada’s prescription painkiller crisis began more than a decade ago, new figures show.

Preliminary figures from Ontario’s Office of the Chief Coroner obtained by The Globe and Mail show that fentanyl overdoses accounted for one of every four opioid-related fatalities in 2014.

Medical experts say the scope of the problem is still unknown because the coroners’ figures are more than a year out of date. They worry that Ontario is on track to emulate British Columbia and Alberta, where 2015 figures show an alarming spike in deaths linked to fentanyl, which is up to 100 times more potent than morphine and often mixed with heroin and other illicit street drugs.

“There’s a good chance that we’re on the leading edge of a ruinous surge in heroin and fentanyl-related deaths in Ontario,” said David Juurlink, head of clinical pharmacology and toxicology at Toronto’s Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre.

The Alberta government announced last week that it is addressing fentanyl’s “devastating impact” by making naloxone – a first-aid drug that reverses the symptoms of an opioid overdose – available free of charge to Albertans with a prescription. Fentanyl overdoses claimed 272 lives in Alberta last year.

In British Columbia, where fentanyl was detected in nearly one-third of all illicit drug overdose deaths last year, medical experts have called for expanded access to naloxone and health-care coverage for it.

Health-care workers suspect a bootleg version of fentanyl was behind a recent surge in Ontario of overdoses that were initially believed to be caused by heroin. Fentanyl was developed as a prescription painkiller, but gained popularity as a street drug after OxyContin, a widely used brand-name version of oxycodone, was removed from the market in Canada in 2012.

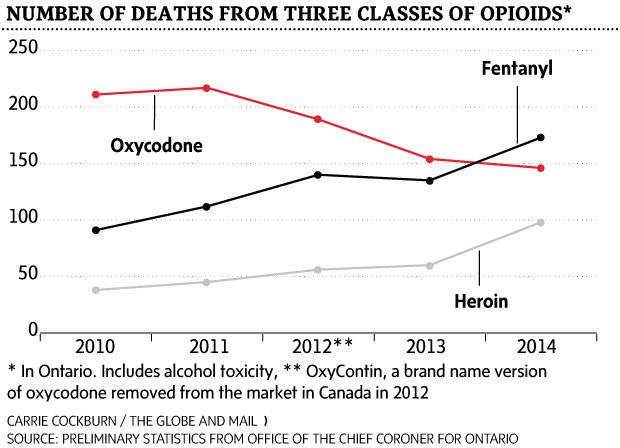

The most recent coroners’ statistics reveal the mounting toll of both fentanyl and heroin. Fatal overdoses linked to fentanyl in Ontario climbed 28 per cent to 173 in 2014, supplanting oxycodone, which was traditionally the major cause of opioid overdose deaths, the coroners’ figures show. Heroin overdoses accounted for 98 deaths, an increase of 63 per cent. In all, 663 people died of opioid overdoses in 2014, including 136 where alcohol was also a factor.

“That trend is startling and a clear message for action,” said Kieran Michael Moore, associate medical officer of health for KFL&A Public Health, an agency representing Kingston and neighbouring communities.

Medical experts said Ontario is ill-equipped to address the opioid crisis, which ranks as a leading cause of accidental deaths in the province. They are calling for pre-emptive measures to manage the outbreak, including wider availability of naloxone.

Michael Parkinson, a co-ordinator of the Waterloo Region Crime Prevention Council, which recently launched an alert system to monitor the opioid crisis in the local area, criticized Ontario for an “absence of leadership and a paucity of resources devoted to overdose prevention.”

Every province should follow Alberta’s lead in making free naloxone kits available, Mr. Parkinson said.

In British Columbia, opioid users with a naloxone prescription can pick up kits for free at 146 locations in British Columbia under a pilot program. Launched in August, 2012, the program has trained more than 6,300 people and distributed more than 5,500 kits. It is credited for reversing at least 434 overdoses.

Outside the program, naloxone costs $2 to $14 a dose and can be prescribed only to the user. Most extended health-care plans will cover it, but not B.C. PharmaCare, the basic coverage most British Columbians have.

Earlier this month, firefighters in Vancouver and Surrey became the first in British Columbia to carry the antidote.

KAREN HOWLETT AND ANDREA WOO

TORONTO and VANCOUVER — The Globe and Mail

Published Sunday, Feb. 21, 2016 9:25PM EST

Last updated Sunday, Feb. 21, 2016 10:41PM EST