When Donald Trump took the stage after his decisive victory over Nikki Haley in the New Hampshire primary, he was in no mood to celebrate. Rather than cheering the seemingly inexorable momentum of his bid for the Republican presidential nomination, he spent most of his speech complaining that his last remaining opponent hadn’t dropped out of the race.

The former U.S. president called Ms. Haley an “imposter,” disparaged her dress and claimed without evidence that she has mysterious scandals “she doesn’t want to talk about.”

While the anger was vintage Mr. Trump, it was also telling of the sense of inevitability that permeates his campaign. After driving a dozen competitors out of contention before the vast majority of ballots have even been cast, Mr. Trump clearly expected New Hampshire to finish the job. Ms. Haley had other plans. She vowed on Tuesday night to keep fighting, even as her already narrow path to the nomination has all but closed off.

Here are five questions hanging over the nomination battle and the answers we might glean from the result in New Hampshire.

Does Ms. Haley have any shot at all?

As the former United Nations ambassador and onetime South Carolina governor pointed out, only two small states have voted so far. Her home state holds its primary on Feb. 24, and 15 more contests will take place on March 5, including populous California and Texas.

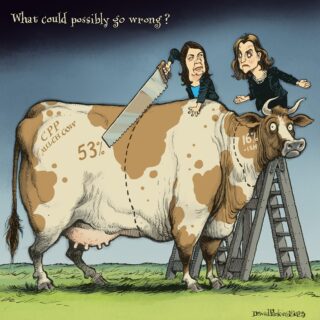

The problem for her is that she faces significantly harder races in many of these places than she did in New Hampshire. Recent polling in South Carolina, for instance, found Mr. Trump with more than 60 per cent support and Ms. Haley with around 25 per cent.

A key factor is that most states allow only Republicans to vote in their Republican primaries, which wasn’t the case in New Hampshire. Famously moderate and independent-minded, nearly 40 per cent of New Hampshire voters are registered as “undeclared” – supporters of no party – and the state makes it easy for them to vote in whichever primary they choose. According to CNN’s exit polling, about 70 per cent of Ms. Haley’s supporters in New Hampshire were undeclared voters.

The bottom line: If she couldn’t beat Mr. Trump in New Hampshire, it is hard to see how she could do so in more conservative states where independents can’t help her.

Why do these small states matter?

The first two states to vote, Iowa and New Hampshire, have a combined population of less than five million people and demographics that skew far whiter than the country as a whole. But they have outsized importance in picking presidential candidates (or at least winnowing the field by eliminating lower-performing contenders.)

Part of it has to do with money. Doing poorly in Iowa and New Hampshire can cause wealthy donors to walk away, depriving candidates of the ability to continue on to larger states. Much of it is also a question of momentum. Performing well in early states can create a perception of strength that attracts voters later on.

How will Trump’s legal battles factor in?

The former president’s Republican rivals calculated that his 91 criminal charges and multiple civil suits would work against him. Either voters would be turned off, the thinking went, or he would find it too difficult to continue his campaign.

That has not been the case. Not only has Mr. Trump’s polling among Republican voters improved with the indictments, but he managed to repeatedly skip campaigning in Iowa and New Hampshire to attend court dates without apparently affecting his performance.

There is also nothing that bars a convicted criminal from serving as president. Attempts to get Mr. Trump off the ballot under the 14th amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which blocks insurrectionists from holding office, have so far succeeded only in Colorado and Maine, two states that won’t play much role in deciding the presidency. Mr. Trump has appealed those decisions to the Supreme Court.

How do the Democrats feel about this?

President Joe Biden won in 2020 by assembling a wide-ranging voting coalition united only by their desire to defeat Mr. Trump. He’s hoping to do the same in November, and this week’s results give him some cause for optimism.

The large number of independent voters who went for Ms. Haley suggests that Mr. Biden may be able to persuade those same voters to hold their noses and support him if Mr. Trump is the Republican nominee.

Voter turnout was high for a primary, with more than 300,000 people casting ballots in the Republican contest, a record total for the state. Both parties will no doubt read this positively: Mr. Trump for his ability to draw support from people who don’t ordinarily vote, and Mr. Biden for Mr. Trump’s ability to drive turnout from people who oppose him.

What’s happening with Nevada?

Typically the third state on the primary calendar, Nevada’s Republican contest is not really a competition this year, owing to a dispute between the state legislature and the local GOP.

The legislature passed a law replacing the state’s caucus system – in which everyone gathers to vote simultaneously at a specific time – with a regular primary, where voters cast secret ballots. But the state Republican Party is going ahead with caucuses anyway.

The party is banning any candidate who runs in the primary from taking part in the caucuses. So Ms. Haley is a candidate in the Feb. 6 primary, but not the caucuses, while Mr. Trump is a candidate in the Feb. 8 caucuses, but not the primary. Only the caucuses will assign delegates to the Republican National Convention. Consequently, Ms. Haley is effectively not bothering to campaign in Nevada.

It means she will be focusing intently for the next month on South Carolina. What remains to be seen is whether she can gather any momentum, or whether the lengthy interval will simply make her run out of steam.

ADRIAN MORROW

U.S. CORRESPONDENT

The Globe and Mail, January 24, 2024