A slice of foodie culture has arrived at Metro Inc.’s newest supermarket, which features a lush wall of veggies, dozens of exotic cheeses, a slow-cooking rotisserie, a sushi bar and organic offerings.

Think Mimolette D’Isigny cheese from France for $99.99 a kilogram.

It’s Metro’s version of the gentrified grocery store, a bid to tempt urban consumers and boost business by focusing on a smorgasbord of fresh foods – with some higher prices and fatter profit margins – even as shoppers are courted by a growing array of discount retail options.

Masterminding the Metro makeover is Carmen Fortino, a former executive at arch rival Loblaw Cos. Ltd. whose heritage is the Fortinos supermarket chain that bears his family’s name and was bought by Loblaw in 1988.

Now Mr. Fortino, a second generation member of Fortinos founding family, is fighting the grocery wars from the other side of the battle field.

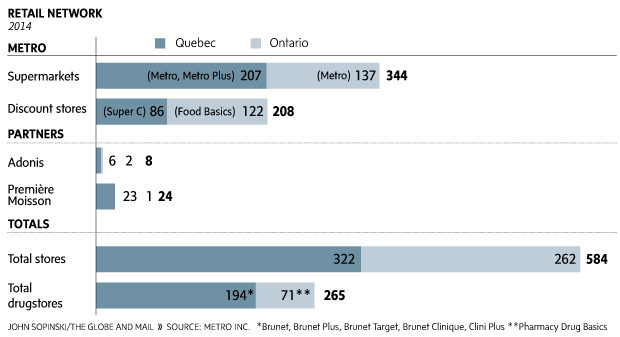

“It’s intensely competitive, that’s what makes it fun,” Mr. Fortino said in an interview on the eve of Thursday’s launch of the new Metro prototype store surrounded by condominiums in Toronto’s west Lakeshore area. Over the next three to five years, the company will update most of its 137 Ontario Metro stores with an emphasis on fresh foods, he said.

Mr. Fortino, who started six months ago as head of Metro’s Ontario division, needs to win. Metro’s Ontario business underperforms operations in its home province of Quebec.

Metro is now betting on Mr. Fortino and his deep experience at Loblaw, including the fresh-food strength of its Fortinos, to give Metro a boost.

“Carmen is a veteran of that market and understands the dynamics of it and what needs to be done,” said Peter Chapman, president of grocery consultancy GPS Business Solutions and a former Loblaw executive.

But Loblaw and Sobeys Inc. are both focusing on improving their fresh premium offerings as well, making the mainstream market a crowded one, Mr. Chapman said. Upscale U.S.-based Whole Foods Market also has an ambitious expansion plan for this country. And the Weston family that controls Loblaw is believed to have the licence to operate the Italy-based food emporium Eataly in Canada and is looking for sites. (An Eataly spokeswoman said Canada is “of interest” but “no decisions have been made yet.”)

“For sure foodies are a big part of what we’re trying to attract to these stores,” said Jason Potter, who heads a division of Sobeys that is rolling out its next-generation Sobeys Extra format, which also touts more fresh and healthy offerings.

At the same time, the estimated $121.2-billion-a-year grocery market has been shifting to discount formats, including titan Wal-Mart Canada’s added food aisles. In the 52 weeks ended Dec. 27, the share of the industry’s discount segment rose 4 per cent to 40.5 per cent per cent from a year earlier, while the conventional market dropped 1 per cent to 59.5 per cent, according to researcher Nielsen.

But the tide is beginning to turn as retailers invest in premium flagship stores, said Carman Allison, a Nielsen vice-president. They’re being dubbed “grocerants” for taking on restaurants with ready-to-eat fare whose sales jumped 9 per cent in 2014 from a year earlier, he said.

Metro doesn’t break out its Ontario and Quebec results, but its overall same-store sales are improving from the tough days in 2013 and 2014 when U.S. discounter Target Corp. was expanding in Canada. Those sales at outlets open a year or more, an important retail measure, grew 3.8 per cent in Metro’s last quarter, mostly driven by inflation.

Retail analyst Perry Caicco at CIBC World Markets called out Metro’s Ontario operations as “a serious problem” late last year, noting it probably makes “very little actual operating profit,” excluding funds it gets from suppliers for prominent shelf space and other initiatives.

More recently, with Target’s impending exit, Mr. Caicco has struck a brighter tone: “Their Ontario stores seemed in need of a massive refresh, but just by waiting out the terrible 2013-2014 grocery market, the stores are now poised for solid same-store sales growth.”

Mr. Fortino, whose first job as a teenager was stocking shelves part-time at Fortinos, is catering in the new Metro store to condo-dwelling young professionals with disposable incomes to splurge on fresh and take-out food. The uncluttered look of the store is also a departure, with brushed concrete floors, stainless steel accents and dark-wood produce tables. Another new element is a Starbucks café, underscoring the upmarket environment. And to drive home the community flavour, it has put Humber Bay Park on the store sign.

The new store devotes 60 per cent of its space to fresh foods, including prepared fare, compared with 40 per cent in regular Metro stores, Mr. Fortino said. For instance, it carries 63 varieties of chilled dips, about twice the number at a standard Metro.

But the new store stocks fewer large family packs because local condo residents have little storage space, he said.

Fresh food is important because it can generate up to 20 per cent higher gross margins than packaged goods, he said. But it can spoil more quickly and need to be tossed, as well as require more labour to handle the goods.

Metro is spending $300-million overall on its stores in 2015, much of it to upgrade conventional stores. That’s up from $250-million last year when investments were more heavily directed to improving the retailer’s Food Basics discount outlets.

Already elements of the new offerings are in various Metro stores, he said. “You’ve got to be awake in this business, otherwise you’re not going to be around,” Mr. Fortino said. “We’re not afraid to invest. We just want to do it properly. … We’re going to go as fast as we can.”

MARINA STRAUSS – RETAILING REPORTER

The Globe and Mail

Published Wednesday, Mar. 25 2015, 7:03 PM EDT

Last updated Thursday, Mar. 26 2015, 6:48 AM EDT