As central banks outside of the United States race to the bottom on interest rates, the flight to the U.S. dollar on the promise of rising rates by the Federal Reserve is creating a new risk: That the healthy American economy could catch cold from the global rate-cutting frenzy.

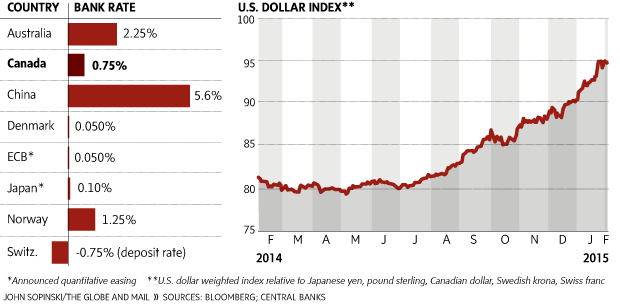

Australia added to the fast-growing list of countries easing their monetary policy, cutting its key rate to 2.25 per cent from 2.5 per cent Tuesday. Since the Bank of Japan surprised financial markets with an increase to its monetary stimulus program in late October, nine prominent central banks, including the heavyweight European Central Bank and the People’s Bank of China, have eased their policy in the face of sluggish economic growth and oil-fuelled disinflation. Canada joined the list last month, trimming its key rate to 0.75 per cent from 1 per cent – with the markets betting on another cut from the Bank of Canada by spring.

As the rate-cutting snowballed in recent weeks, market watchers say “competitive devaluation” is playing a growing role. Countries appear to be lowering rates at least in part to discourage investors from buying their currency, as they jockey for position with trading partners doing the same. A lower currency improves price competitiveness of exports, and countries are looking for any edge to protect their share of the global trade market and keep their sluggish economies moving.

“I don’t want to say ‘currency war,’” said Mark Chandler, head of Canadian fixed-income and currencies strategy at RBC Dominion Securities. “But it’s hard to say this isn’t being motivated by a need to get that stimulus moving through the foreign exchange.”

This has left the Federal Reserve, presiding over a healthy and accelerating economy, as the world’s sole significant central bank looking to raise rates rather than cut them. (Even the Bank of England, which makes its next policy announcement on Thursday, is seen moving away from a rate-hiking direction to a more neutral, hold-the-line stance.) This widening rate gap has sparked a stampede to the U.S. dollar in search of higher returns, driving the currency up 17 per cent against a basket of other major currencies since the middle of last year. That, experts say, is creating a headwind for the U.S. economic expansion.

Signs of the currency drag appeared in the recent U.S. fourth-quarter gross domestic product estimates, showing that economic growth slowed to an annualized rate of 2.6 per cent in the fourth quarter from 5 per cent in the third quarter. While strong growth earlier in the year was highlighted by booming goods exports, those exports slowed to a crawl in the fourth quarter. Meanwhile, imports surged, as the strong dollar made foreign goods cheaper.

New economic indicators this week added to the evidence. Factory orders slumped 3.4 per cent in December, on top of a 1.7-per-cent fall in November. And the Institute for Supply Management’s Manufacturing Purchasing Managers’ Index fell to its lowest level in a year for January, indicating that manufacturing growth has slowed.

U.S. corporate earnings are also showing scars of the inflated currency, as S&P 500 profits for the fourth quarter look to have grown at only about half the pace of the third quarter.

“The latest results and tone from the corporate sector tend to confirm what the economic data are saying – the surging U.S. dollar is going to be a drag on economic growth in the year ahead,” said Bank of Montreal senior economist Robert Kavcic in a research report.

With economies outside the United States struggling and the U.S. dollar surging, economists believe U.S. growth in the coming months will have to depend more on demand from U.S. consumers, who are getting a break both from the sharp drop in energy prices and from the strong currency reducing the cost of imported goods. New data released Tuesday showed that U.S. personal disposable income grew by 0.5 per cent in December, the strongest month in two years, indicating that consumers are poised to spend; but disappointingly, personal spending fell 0.3 per cent in the month.

The currency- and oil-related price breaks for U.S. consumers are also taking a big bite out of U.S. inflation, a key determinant of the Fed’s interest rate policy. Many economists are now projecting that inflation in the United States could barely top 1 per cent this year, far below the Fed’s goal of about 2 per cent – although the Fed has indicated that it considers oil’s impact, responsible for much of the slowdown, as a transitory effect. While the Fed so far has continued to indicate a midyear rate increase, financial markets have their doubts – current pricing in the markets suggests an expectation for perhaps only one Fed rate increase late in the year.

Meanwhile, the rate-cutting trend outside the United States likely isn’t over, including in Canada, where the oil shock threatens to take a big slice out of economic growth. With crude still well below the $60 (U.S.) a barrel assumption the Bank of Canada used for its January economic forecasts, economists and financial markets see another quarter-percentage-point rate cut as increasingly likely. Based on the pricing of interest-rate swaps, traders see a 60-per-cent likelihood that the Bank of Canada will make another cut at its next meeting, in early March, and a 90-per-cent chance it will cut by the mid-April meeting.

DAVID PARKINSON – ECONOMICS REPORTER

The Globe and Mail

Published Tuesday, Feb. 03 2015, 7:20 PM EST

Last updated Tuesday, Feb. 03 2015, 11:25 PM EST