Canadian universities are reporting a rise in academic misconduct cases in recent years, a trend that was exacerbated by the pandemic.

In March, 2021, a student at the University of Toronto found a tutor online and hired him to surreptitiously write an exam on his behalf.

In return for a $60 fee, the tutor used the student’s ID and password and joined the exam, which was being conducted online. The 90-minute test was worth 20 per cent of the grade in a first-year accounting class. The student didn’t want his stand-in just to squeeze by, though. He wanted an A. “I need at least 80+ to achieve my goal, so please make sure you have the ability to do that,” the student wrote.

The tutor took the exam without anyone noticing. When the marks came back, however, the professional stand-in had scored only 62 per cent. His client wanted better than that. If he was going to hire the tutor for the final, he wrote, he had to promise a grade of 85 or higher. “Otherwise I can’t even get into my major next year,” the student wrote.

A few days later, the tutor, perhaps irked by the complaint, revealed his fraud in an e-mail to U of T Mississauga accounting professor Catherine Seguin. When Prof. Seguin confronted the student, he apologized and begged for leniency, blaming the strain of the pandemic.

Five days later, though, he hired someone to write his environmental science exam for $400, only to be caught by a teaching assistant. Over the next few months he was put through a tribunal, which is the standard practice at universities when students are accused of serious misconduct. His communication with the tutor and Prof. Seguin, neither of whom responded to requests for comment, was described in the case record.

The student, identified in tribunal documents as H.M. (names of students accused of cheating are kept secret under university rules), was found guilty on two counts and suspended from the university for five years.

His case is just one of thousands of examples of a large and troubling trend exacerbated by the pandemic. More students appear to be breaking academic integrity rules than in the past, and more are getting caught.

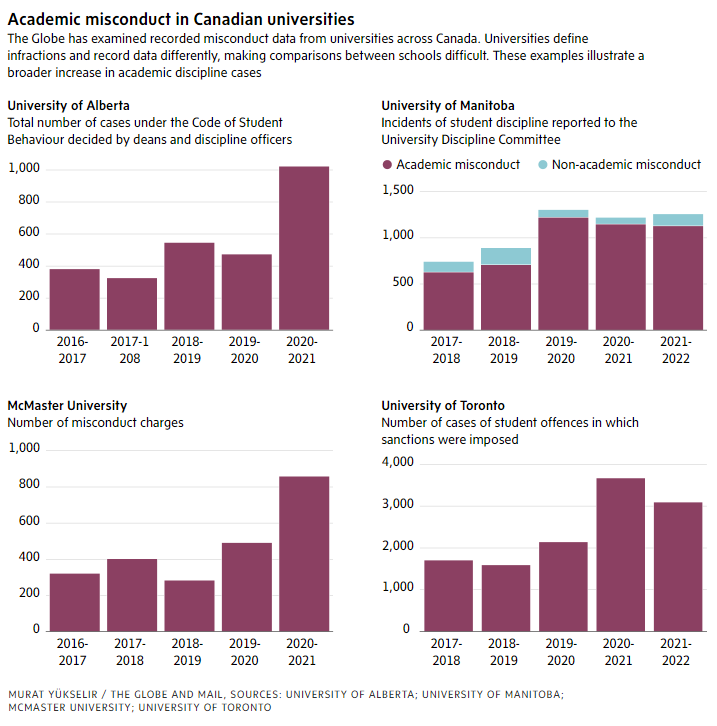

At the University of Alberta, the number of academic discipline cases doubled in 2020-21 compared to the previous academic year, to more than a thousand. The number of cases also more than doubled at the University of Saskatchewan, and nearly doubled at McMaster.

At the University of British Columbia, more than twice as many students appeared before the president’s advisory committee on student discipline than in the year before. And at the University of Toronto and Queen’s University, cases doubled over the two-year period from 2019 to 2021.

Comparisons across institutions can be difficult in Canada because cases are categorized differently, but the general trend is clear: allegations of academic misconduct – meaning unauthorized help, cheating, plagiarism and other acts of dishonesty or misrepresentation – have risen sharply at many schools.

Some blame the pandemic for the increase. COVID-19 forced exams and other evaluations online and may have offered more opportunities for discipline breaches. A spike in academic misconduct occurred in other countries as well, suggesting a broader social trend.

The numbers have decreased as schools have restored in-person learning and assessment, but they remain elevated in some places. At the University of Toronto, there were 3,092 cases in which sanctions were imposed on students in 2021-2022, a 15-per-cent drop compared to the year before. Still, that’s 95 per cent higher than in 2018-19, the year before COVID-19. And it represents more than 3 per cent of U of T’s student population.

But only 161 of those cases went to tribunals. The rest were resolved at lower levels of the university’s disciplinary system.

H.M.’s case is an example of contract cheating, which is considered one of the most serious types of academic dishonesty. Paying someone to take a test or write a paper requires planning and deception that any student would recognize as wrong. The contract cheating industry was estimated by scholars a few years ago to generate more than a billion dollars annually, worldwide. A more recent estimate by a Canadian academic, Sarah Elaine Eaton, puts the figure closer to US$21-billion annually.

Prof. Eaton, who works in the faculty of education at the University of Calgary, is a leading voice on the study of academic integrity. In 2020, she made headlines with research that estimated 70,000 students at Canadian universities buy cheating services every year.

She based that number on a 2017 meta-study from Australia that pulled data from more than 1,300 surveys around the world. It found that about 3.5 per cent of university students globally would admit to contract cheating. (Various studies place the incidence as low as less than half a per cent and as high as nearly 8 per cent.) But during the pandemic, the same research group found the incidence in Australia was 12 to 15 per cent. Prof. Eaton said Canada likely also saw an increase during that period.

A 2021 study at the University of Lethbridge found that nearly half of students (45 per cent) had witnessed cheating in some form. But a much smaller percentage admitted to doing it themselves. Seven per cent said they had used the same work in more than one class, which is not permitted, while 1.5 per cent said they had turned in work completed by other people. And 0.4 per cent said they had submitted work they had paid other people to produce.

One of the issues that arises in academic integrity cases is that it’s almost always up to the professor to detect the cheating and decide how to proceed.

Five decades of research in Canada and the U.S. have shown that only about one in two professors will report academic misconduct, according to Prof. Eaton.

They might hold back for fear of jeopardizing a student’s career, or they might not want the unpleasantness of a potential conflict, or the work involved in taking an academic misconduct charge to a dean.

They might suggest a student withdraw from a course or just redo an assignment, saving everyone the trouble – or that they take a zero on an assignment and continue without a formal disciplinary process. In those cases, the incidents might not be captured in university statistics.

Of professors surveyed at Lethbridge, only 50 per cent said dishonesty should always be reported. And while 92 per cent of faculty said they had witnessed dishonesty, only 81 per cent said they had reported it. About 10 per cent of faculty said that they didn’t make reports because doing so was too time-consuming or required too much work on their part.

The cases that are certain to be captured in statistics are those that get referred upward to a dean. Most cases are decided at the dean’s level, where penalties for students can include failing grades, or referral to remedial programs on academic integrity.

One such program, run by the library at UBC Okanagan, had 335 per cent more referrals in 2020-21 than it did in the previous year, according to a report to the university’s senate. Of the new referrals, 43 per cent were for issues such as cheating and collusion, and 56 per cent were for plagiarism.

When UBC’s Kelowna campus began its academic integrity program a few years ago, it initially served only about a dozen students a year, said Leah Wafler, who has worked in the program since 2016. But she said the program has grown quickly since it became a diversion option for discipline cases. Last year was a record year, but it’s on track to surpass those totals this year.

Ms. Wafler, like many who work in the academic integrity field, has a great deal of sympathy for students accused of wrongdoing. She said students who turn to cheating are often simply unprepared for university. They fall victim to poor time management and feel family pressure to achieve certain marks.

Instructors and university staff who work on academic integrity issues describe a trio of factors that can lead a student to commit an integrity offence: pressure, opportunity and rationalization. The pandemic certainly offered more opportunities to cheat, and, when there’s a sense that everyone else is doing it, it can be easier for students to rationalize, Ms. Wafler said.

But what seems an easy way out often ends up costing the students dearly, she added. “It’s never as good as they might think. The stress of an accusation of misconduct is so much worse than possibly getting a lower grade on an assignment.”

Summaries of academic misconduct cases published by the University of Manitoba read like a litany of misguided attempts to outsmart the system. A student caught accessing his exam from two different IP addresses was given an F in a course and suspended for a year. A contract cheater lied when confronted about submitting another person’s work, was betrayed by his collaborator and expelled. A student hired a freelancer to complete an assignment, got an F in the course and was suspended for a year.

The 40-word tragedies go on for 10 pages. They only capture those who are caught, though. Many likely get away undetected.

“Schools only catch bad cheaters, not good cheaters,” said Alysson Miller, an academic integrity specialist at Toronto Metropolitan University. “If students are not in the classroom to learn, there’s not a whole lot you can do about it. The best thing you can do is try to make an environment where people do want to learn, if you can.”

Jennie Miron, a professor of nursing and chair of the Academic Integrity Council of Ontario, said dishonesty has been around as long as there have been students in school. Studies show students are most likely to run into trouble when they’re under stress, and “on a scale from one to 10, the pandemic put us all at 11,” Prof. Miron said.

The statistical spike at the height of the pandemic may also partly reflect frustration among professors dealing with new online evaluation methods. Out of their element and concerned that students were taking advantage of the situation, instructors may have been more apt to report misconduct than in the past.

In H.M.’s case, remote learning could have been a factor. He was enrolled at U of T Mississauga but attended classes online from his home in China because of travel restrictions. He said he spent much of the year in isolation and struggled on his own without friends, while also coping with the divorce of his parents. Like many students accused of cheating, he was in first year. About half of misconduct cases at the University of Alberta in 2020-21, for example, involved first-year students. At his tribunal hearing, H.M. said he didn’t understand the significance of academic integrity when he chose to cheat.

Today, university bulletin boards and cafeteria tables are regularly festooned with offers of tutoring help. Google any subject area and the words “test help” and the sponsored ads will start appearing from sites offering to write exams for payment. The subtler versions of these sites promise help that stays within the rules, but, once the relationship is established, the offered help can veer into cheating. At that point the tutoring company, which can be anywhere in the world, has the student’s credit card information. What they offer seems so easy. For a student who’s anxious and afraid of failure, the lure of an easy way out can be overwhelming.

Once a student has communicated with a cheating service, they can be extorted, because they often give these companies their names and the names of their schools. The companies may keep charging students for tutoring services every month until their credit cards expire. And if the students try to cancel the payments, the companies can threaten to contact university administrators and expose the cheating. “Blackmail and extortion are part of the business model,” Prof. Eaton said.

The advent of artificial intelligence tools, such as ChatGPT, could make it easier for cheating services to quickly turn out essays and test answers that are difficult to detect as frauds. There are rumblings, Prof. Eaton said, that AI is already being used to cut down on human resource costs in the contract cheating industry.

Recent scandals have cast a spotlight on cheating in Canada and its potentially significant consequences. In June, Ontario’s Law Society received a tip that some candidates taking the online bar exam in November, 2021 had professional help. An investigation found that a tutoring company was helping students cheat. Twenty-one students had their exam results voided or received failing grades, and 126 had their exam results and articling experience voided and were prohibited from reapplying for a year.

Late last year, Ontario’s Auditor-General revealed that more than 300 students were caught cheating on the real estate licensure exam offered by Humber College. In this case, the misconduct appears to have been an organized scheme that took advantage of an online test format that couldn’t detect when a test-taker was allowing a third party to see their screen.

Prof. Eaton said the pattern in Canada has been to treat academic misconduct as something that happens in isolation. Media stories tend to examine one incident at a time, she said, and institutions cross their fingers hoping to avoid being cast as “the bad one.” But the problems are the same everywhere.

Higher education is one of Canada’s largest export industries, valued at over $22-billion. The country has a lot at stake in maintaining a reputation for academic quality and integrity.

Prof. Eaton said Canada’s competitor nations in the industry, such as Britain, New Zealand and Australia, have taken more steps to co-ordinate their approaches to academic integrity.

In Australia, where a major contract cheating scandal broke out a decade ago, the national quality assessment board is responsible for enforcing a law, passed by the national legislature in 2020, that prohibits academic cheating services. The law makes it illegal to provide or advertise a cheating service, and it authorizes punishments of up to two years in prison if money changes hands. New Zealand passed a similar law in 2011, as did Britain in 2022. But Canada still allows contract cheating services to advertise and operate.

“This is something that governments need to tackle,” Prof. Eaton said.

JOE FRIESEN

POSTSECONDARY EDUCATION REPORTER

The Globe and Mail, February 16, 2023