More than 2.3 million have escaped Ukraine and fled to neighbouring countries, filling train stations and border towns.

Anna Serdechna travelled from the United States to reach the central train station in Bratislava, Slovakia, where she waited to catch her train to Kosice, a city in the eastern part of the country. From there, she will take a bus to Uzhhorod, Ukraine, which is just on the other side of the border, where her mother and 11-year-old niece are waiting for her.

Ms. Serdechna has lived in the U.S. for nine years, working in North Carolina as a photographer, but felt she needed to return.

“My mom is older, she’s never been abroad, she doesn’t know English and I don’t feel like it is safe even for both of them just to be alone, so I wanted to help them out,” she said.

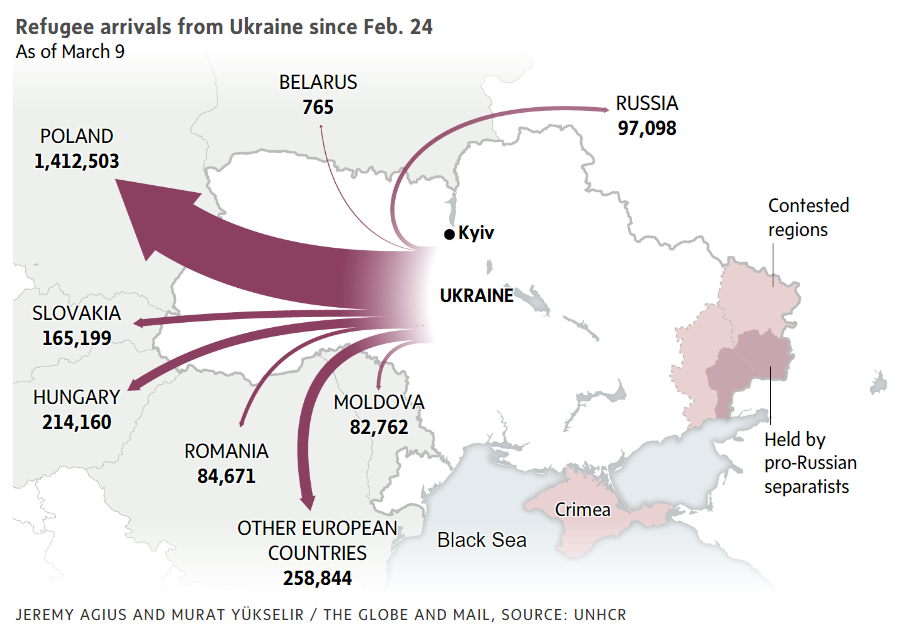

Since Russia invaded Ukraine two weeks ago, the escalating war has led more than 2.3 million people to flee Ukraine to neighbouring countries, according to United Nations data. Officials expect the number to increase as thousands of refugees continue to cross over their borders every day.

So far, more than 165,000 people have arrived in Slovakia, and 1.4 million in adjacent Poland. At the borders of those countries, loved ones and members of the Ukrainian diaspora, along with volunteers from across Europe, are crossing into Ukraine to bring out relatives and strangers, and to offer help to those in need.

Ms. Serdechna said she is originally from Eastern Ukraine; her family lived in Luhansk before moving to Dnipro eight years ago because of the war in the Donbas. They left their home there after Russian forces attacked the Zaporizhzhya nuclear power plant last week.

“For now at least I can take the child out from there,” said Ms. Serdechna, whose sister has decided to stay in Ukraine with her husband. (Most men between the ages of 18 and 60, who could be conscripted, have been prevented from leaving the country.)

“It’s horrible what happened. … I’m happy that I can help at least somehow, but still my heart will be there.”

It took her mom and niece about four days to reach the Ukrainian side of the Slovakian border, as they dealt with traffic inching slowly and several police checkpoints. Sometimes they stopped to sleep in schools along the way.

“Nobody would expect that would ever happen. Like for my family … we already had a bad experience running away from the bombs. But this big, this much, nobody would ever imagine.”

While Ms. Serdechna was heading toward Ukraine earlier this week, nearly everyone else at Bratislava’s central train station had fled that country.

Thousands of refugees have transited through the station since Russia invaded. And while most have continued on to other countries, some have stayed after being welcomed by Slovakia, a country of 5.4 million.

The government is granting temporary protection to Ukrainian citizens and their relatives, providing them with health care and social protection including benefits, and giving access to the labour market and the education system.

The government said it will also give money to those who provide refugees with temporary protection and shelter. Slovak households and organizations will receive €210 ($295) a month for each adult and €105 ($147) for every child they house.

According to the Kto pomoze Ukrajine initiative, 39 organizations and more than 1,000 volunteers are supporting Ukrainians who have fled to Slovakia. And so far Slovakian NGOs have raised €3,228,879 ($4,530,000) from donors, according to Darujme, the country’s largest donation system.

ZSSK, the national rail line, recently introduced daily emergency evacuation trains from Chop, Ukraine, to Kosice, and all train tickets on the system are free for Ukrainian citizens.

Next door in Poland, volunteers are working to help people cross the border by whatever means possible.

When Nadim Butierrez heard that someone in Basel, Switzerland, was looking for a friend from Ukraine who was trying to get across the border, he didn’t think twice about jumping in his car and driving down from his home in Zurich.

Mr. Butierrez, who works in insurance, had joined a WhatsApp group that exchanges news and offers of help for Ukrainian refugees. After he spotted the appeal, he drove 15 hours to Przemysl, a city in eastern Poland that’s close to the boundary with Ukraine. “I told my wife I have to go,” Mr. Butierrez said.

And he didn’t hit the road empty-handed. He loaded his car with medicine and other supplies and dropped everything off at a giant refugee shelter in a vacant shopping plaza outside of Przemysl.

But finding the friend proved challenging. He spent hours searching in Przemysl without any luck. “It was pretty chaotic there,” he recalled. Finally he got word that the person could be at a shelter in Radymno, close to another border crossing about 40 minutes away. The tip paid off. Mr. Butierrez found the friend, along with her dog and cat.

As he prepared for the return journey to Basel on Monday, Mr. Butierrez was asked whether he’d do it again. “I might, for sure,” he said. “I like to drive.”

In Oleszyce, a small Polish town near the border with Ukraine, a group of around 60 locals have banded to run a convoy of food, medicine, blankets and other essentials to people still on the other side who are trying to cross over. The group also drives across the boundary and picks up people who are too ill to make the journey on foot.

“We are not an organization, we are just volunteers,” said Martin Piotrowski, who has helped organize the effort. “We’re making more sandwiches than McDonald’s. We’re feeding 10,000 people a day.”

Mr. Piotrowski said his group – which includes 10 drivers who make as many as six trips a day – has built shelters and erected heated tents for people waiting in line on the Ukrainian side. They’ve also set up a medical centre and have been sending food and other supplies to communities along the border in Ukraine.

“They are starving in some places, really it’s so bad,” he said. His main focus is helping Ukrainians get across as quickly and safely as possible, sometimes using wheelchairs or buggies. “Our job is to feed the people, keep them warm and keep them moving.”

THE GLOBE AND MAIL

JANICE DICKSON

PAUL WALDIE, EUROPE CORRESPONDENT

The Globe and Mail, March 11, 2022