Indigenous-managed conservation areas are key to Canada’s pledge to designate nearly one third of its land and ocean waters for biodiversity protection by the end of this decade, according to a new report.

The report from World Wildlife Fund (WWF) Canada stresses that protected areas should be “co-developed and implemented with Indigenous consent” as part of Canada’s reconciliation process.

Its release on Tuesday coincides with efforts by a group of world leaders, including Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, to press their counterparts on biodiversity preservation ahead of international negotiations in Montreal later this year.

Mr. Trudeau is set to speak at an event on Tuesday evening occurring on the margins of the UN General Assembly, now under way in New York. The event was co-organized by the High Ambition Coalition for Nature and People, a group of more than 100 countries that have all formally endorsed the target of protecting at least 30 per cent of the world’s land and oceans by 2030.

Ottawa has previously committed to the coalition’s 30×30 target as well as an intermediate goal of designating 25 per cent of the country for protection by 2025.

Canada is playing a pivotal role in the global discussion around conserving nature as the host of the next meeting of signatories to the UN Convention on Biodiversity, set to take place in December. The conference, co-chaired by China, was originally scheduled to take place in Kunming in 2020 but delayed by the COVID-19 pandemic and then moved to Montreal. A successful meeting is widely regarded as essential if the world is to avert a looming biodiversity crisis.

In addition to hosting the meeting, Canada faces a significant task with its own commitments.

To date, only 13.5 per cent of Canada’s land area has been given some form of protected status, along with a slightly higher portion of its marine and coastal waters. That leaves the federal government, together with the provinces and territories, only a few years in which to meet the new targets.

“I think, increasingly, we are on a global stage and so the leadership, the action that we are taking matters in many ways, just as much as the announcements that we’re making,” said James Snider, WWF Canada’s vice-president of science, knowledge and innovation.

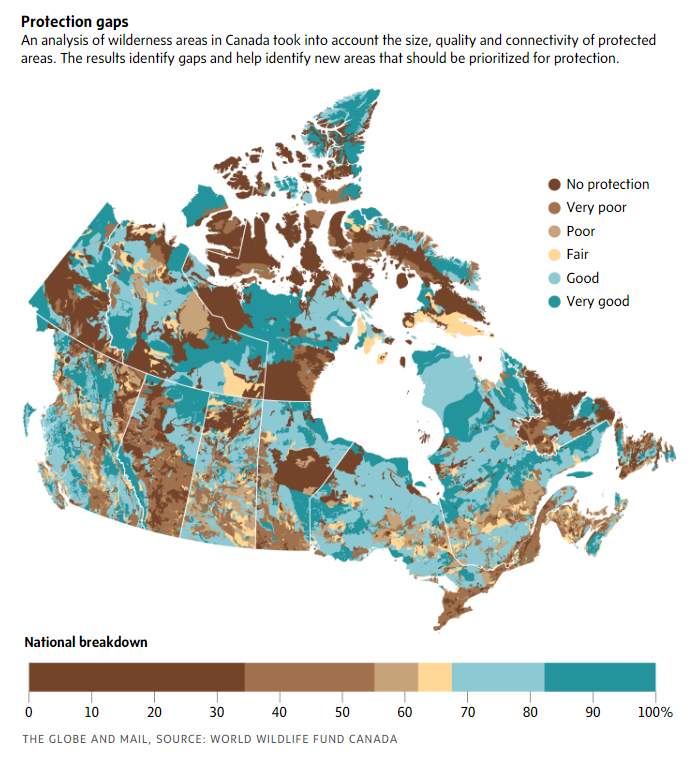

Scientists and conservation groups have long emphasized that what matters is not simply the amount of territory protected but precisely where it is and how it is managed in order to meaningfully safeguard threatened species and ecosystems.

The WWF Canada report is the latest attempt to identify which wilderness areas to prioritize for designated status.

The report identifies several gaps where ecologically sensitive regions are inadequately protected. It then considers where additional protection can be most effective by prioritizing areas that provide multiple benefits. These include preserving habitat for species at risk, storing carbon in forests and soil, providing ecological refuges and corridors to help species deal with climate change and allowing connectivity across the landscape.

Above all, however, the report stresses that Indigenous protected and conserved areas, or IPCAs, should be given high priority for protected status. These are areas where Indigenous peoples play a primary role in conserving ecosystems.

As examples, the report highlights four IPCAs in Canada. They include the Saskatchewan River Delta, the largest inland delta in North America, northern Manitoba’s Seal River Watershed, Nunavut’s Aviqtuuq region, also known as the Boothia Peninsula, and a sprawling transitional zone between forest and tundra, called Thaidene Nene, in the Northwest Territories.

Steven Nitah, an Indigenous conservation leader and a managing director for Nature for Justice, an environmental advocacy organization, said he agrees with the report. Studies show that Indigenous-managed lands are ecologically healthier, he said. Natural areas are also emerging as a key defence in the global response to climate change. Noting that Canada could be looking to international carbon markets as a way to help support conservation on Indigenous lands, Mr. Nitah said. “Why not tie them together as an opportunity?”

The WWF report also prioritizes new areas for protection by looking for overlaps in conservation values to see which geographic locations provide the greatest returns.

Among the areas that emerge from the exercise are large swaths of Labrador, peatlands west of Hudson Bay and much of Baffin Island. Areas with high numbers of species at risk, including B.C.’s Okanagan Valley and the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence River lowlands, also register prominently.

The results dovetail with ongoing work by scientists to provide a more precise and universal means of recognizing high-value ecological sites, called key biodiversity areas, or KBAs. In Canada, a registry for such areas is set to be launched next month.

Peter Soroye, a researcher and outreach co-ordinator for the Wildlife Conservation Society of Canada, praised the report’s focus on protecting and supporting the rights of Indigenous peoples as part of Canada’s approach to conservation.

In the area of species protection, he added that the approach could be broadened to incorporate not only threatened species but entire ecosystems that face elimination.

He said the KBA approach “summarizes all the things that we want to protect most, from a purely biological perspective, into a single tool.”

IVAN SEMENIUK

SCIENCE REPORTER

The Globe and Mail, September 20, 2022