Climate change, tourism and industrial development are changing the waters of the Pikialasorsuaq, which separates people linked by history and bloodlines.

The Inuit of the western edge of Greenland call the tip of Baffin Bay that lies between them and their distant relatives in Canada the Pikialasorsuaq, or “the great upwelling,” because the water is open all year round and teems with the wildlife that has been the staple of their diet for thousands of years.

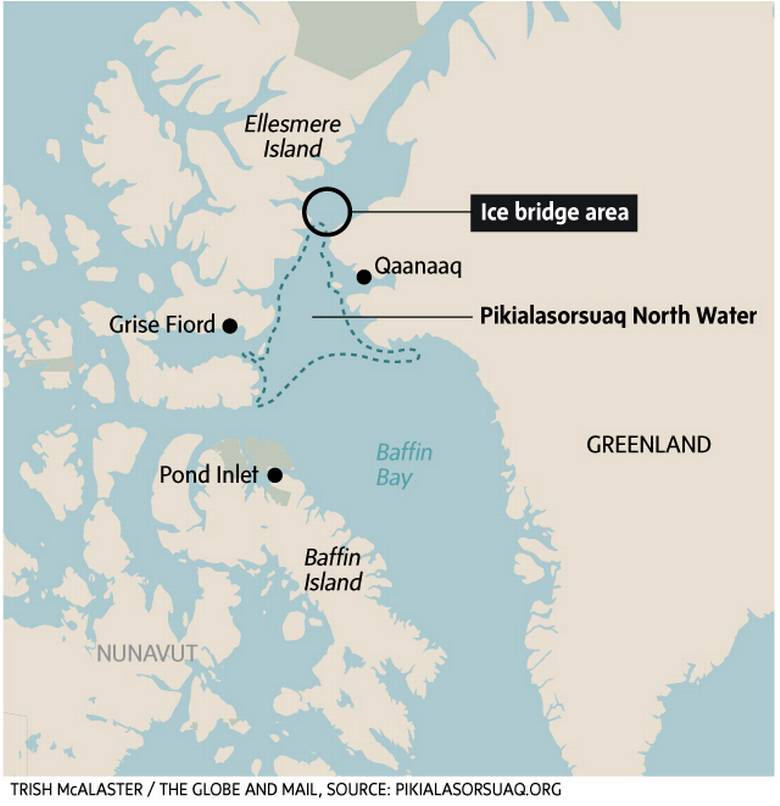

Along the northern edge of the Pikialasorsuaq is an ice bridge that was the migration route from North America taken centuries ago by the ancestors of the Inuit who now live along Greenland’s coast.

It was also the path trekked by the storied Inuit shaman named Qitdlarssuaq around 1850 as he fled Canada with 50 of his followers to escape the vengeance of the family of a man he had murdered.

But climate change, tourism and industrial development are changing the Pikialasorsuaq and threatening the marine mammals that continue to be a primary food source for hunters on both shores. At the same time, the ice bridge, which is the physical link between the northern Indigenous people of the two countries, is becoming less stable and well-defined.

It is an ecological transformation that could eventually deprive the Inuit of both Canada and Greenland of their traditional way of life and their connection with each other.

So they have decided to do something about it.

On Thursday in Copenhagen, a commission that was established last year by the Inuit Circumpolar Council will present a report called People of the Ice Bridge.

It calls for the Pikialasorsuaq to be managed by the communities on or adjacent to the open waters that span 20,000 square kilometres in the winter and expand to 80,000 square kilometres in the summer.

The report says the Inuit want control over such things as shipping, tourism and oil and gas exploration, and hope to create a massive protected area that will encompass the Pikialasorsuaq.

In addition, the report asks for an easing of the travel restrictions – including passport requirements, security checks and customs rules – that, since the terrorist attacks of 2001, have made it difficult for Inuit to cross from one country into the other.

“The most important goal must be to secure the area for the coming generations,” Kuupik Kleist, the representative from Greenland on the Pikialasorsuaq commission, said in a telephone interview on Wednesday. “Historically,” he said, “the sea area and the sea ice have played a very central role for the nomadic way of living and the inhabitation of Greenland.”

The commissioners spent months visiting the communities on both sides of Baffin Bay and asking the Inuit about the changes they have observed in the Pikialasorsuaq. Their recommendations require significant diplomatic sign-on. Canada, Greenland, and Denmark – because Greenland is an autonomous country within the Kingdom of Denmark – would have to give its approval. Nunavut may also have a say.

The first step will be to compile a list of all regulations the jurisdictions have in place to govern the region, Mr. Kleist said, and then to determine what kind of control could and would be exerted by a new management body made up of local Inuit.

The Pikialasorsuaq, known to generations of European whalers as the North Waters, is a polynya, which is ocean that remains free of ice as a result of special air and ocean currents. It takes in waters from the Pacific and the Atlantic as well as freshwater runoff, and is the site of a massive bloom of plankton that attracts Arctic cod. The fish draw marine mammals, including seals and narwhals, which the Inuit hunt.

The ice bridge prevents the icepack from moving into the open water. And it it has allowed the passage of the Inuit from one shore to the other, including that of Qitdlarssuaq. The shaman reintroduced technologies, including bows, fish spears and kayaks, to a small population of Inuit in Qaanaaq whose survival was threatened before his arrival. His descendants still live in the Greenland village.

Chris Debicki, the vice-president of policy development for Oceans North Canada, which promotes conservation in the Arctic Ocean, said the people of the Pikialasorsuaq have a strong political desire to maintain the links they have forged with each other and to manage the area together.

“It doesn’t make sense to protect only one part that falls within one nation’s boundaries without doing the other. You have to look at this thing as a whole ecosystem,” Mr. Debicki said. “We’re looking to see some Canadian leadership on this initiative and hoping that Canada and Nunavut will take some proactive first steps and encourage their partners in Greenland and Denmark to follow suit.”

Paul Crowley, the director of the Canadian Arctic program of the World Wildlife Fund, said the Inuit on both sides of the Pikialasorsuaq are the people “who know the geography, who live it intimately, who have generations of information about it handed down” to them and are in the best position to manage the region on behalf of the rest of the world.

In the process, the report of the Pikialasorsuaq commission says, they want the international boundaries that now divide them to become more porous.

It is difficult to make any distinction between the Inuit of Greenland and the Inuit of Canada, Mr. Kleist said. “The communities that we visited are very, very similar, probably because of their dependency on the area and the wildlife,” he said. “We have so many connections. It’s the same people and it’s the same family.”

GLORIA GALLOWAY

The Globe and Mail, November 23, 2017