University of Manitoba research shows about two-thirds of North American bird species changed their behaviour as humans stayed close to home during the pandemic’s early months.

Birds are just not that into us.

That’s the inescapable conclusion scientists have reached after combing through millions of observations made by thousands of birders across North America before and during the first COVID-19 lockdown last year.

The results are striking because of the depth of human effect on birds, as revealed by our absence, as well as the breadth of species affected, from bald eagles to hummingbirds. Even very common birds, such as the American robin – which is well known in urban areas and seemingly habituated to our presence – had a field day (literally) during the time people were staying close to home.

“About two-thirds of the species that we studied changed the way they used the whole continent,” said Nicola Koper, a professor of conservation biology at the University of Manitoba and senior author of a new study that looked at the effect of the 2020 lockdown on birds. “It was very obvious that it benefitted a lot of species.”

The study, published on Wednesday in the journal Science Advances, is the most comprehensive yet to use the unique circumstances presented by the pandemic to measure the effect on wildlife when human-caused disturbance is reduced. Researchers said the results can be used to inform future conservation measures at a time when many native bird species are in decline because of a multitude of pressures.

Dr. Koper, who specializes in the effects of roads and noise on birds, said she got the idea for the study early on in the pandemic when she had to run an errand in her car and was stunned at the absence of traffic.

“Before I got to the first light, I knew I had to study this,” she said. “It felt immediately like it was going to be a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity – hopefully – to study questions that I’ve been asking for decades.”

The challenge was figuring out how to do it. Biologists were constrained in their movements along with everyone else. And while many casual observers thought they saw more birds while they waited out the lockdown, this could have been because they had more opportunities to notice them.

To counter these effects, Dr. Koper and her colleagues turned to eBird, a massive electronic database of bird observations maintained by the Cornell University Lab of Ornithology. By working with the database – which has continued accumulating records throughout the pandemic – the Manitoba team was able to establish a consistent record of observations for 82 bird species. The team also chose to concentrate on large urban centres with international airports, where the change in activity during lockdowns was likely to be most pronounced.

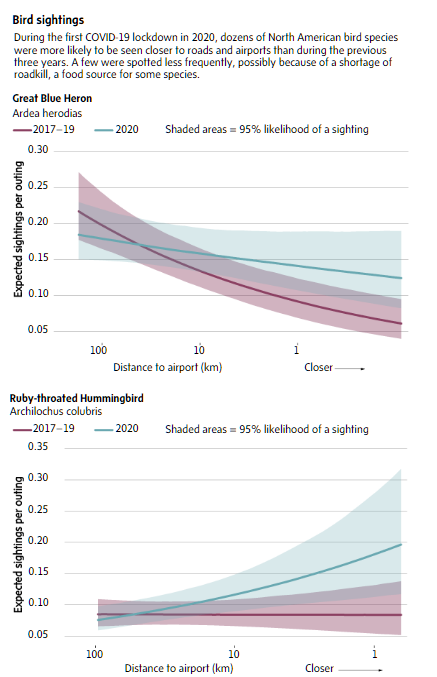

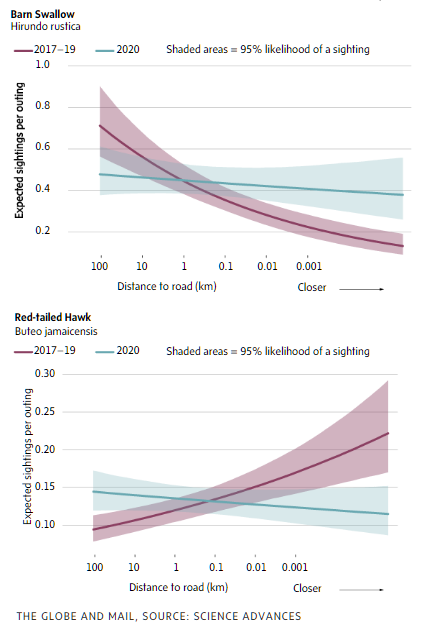

A computer-aided analysis of the data, which took months to prepare, encompassed some four million observations to produce statistically reliable comparisons between what was seen during the lockdown and in the previous three years. For each species, researchers calculated an expected likelihood of a sighting based on previous observations and the change in that likelihood once the lockdown was in effect. These probabilities were also compared at different distances from roads and airports – typically major sources of noise and disturbance.

The results show that during lockdown, many birds shifted their distribution to take advantage of the reduced disturbance, especially species that were in the midst of spring migration. Only a few species were seen less frequently near roads when human traffic was low. One of those, the red-tailed hawk, may have been responding to the absence of roadkill during the lockdown period.

Sightings of some species nearly doubled during the lockdown, including species not previously thought to have been overly affected by certain types of disturbance.

“I never would have thought that the activity at an airport would affect hummingbirds, but that’s what we found,” said Michael Schrimpf, a post-doctoral researcher at the University of Manitoba who led the analysis.

In a separate study published last year, Pierre Legagneux, a biodiversity scientist at Laval University in Quebec, documented improved nutrition and health during the lockdown period among greater snow geese, a species whose annual migration route includes the St. Lawrence River estuary. He praised the team led by Dr. Koper for its rigorous methodology and said the researchers had managed to demonstrate a similar effect at the population level for many more species.

Dr. Legagneux added that one of the most striking details about the results is how quickly birds responded to the change imposed by the lockdown. This suggests that future efforts to reduce the effects of traffic and other forms of disturbance could yield similarly rapid results.

“Any conservation method could have immediate impact,” he said. He added that his latest research has shown that this year, the snow geese appear to be more stressed, as they were before the pandemic began.

Patrick Nadeau, president of the conservation group Birds Canada, said that as people return to their previous patterns of movement, an important takeaway from the study is that day-to-day human activities have a measurable effect on birds.

“It’s all the more reason to address those threats that we can address… because there’s a baseline impact that we can’t do much about,” he said.

IVAN SEMENIUK

SCIENCE REPORTER

The Globe and Mail, September 22, 2021