As climate change disproportionately warms the Arctic, the future looks increasingly bleak for one of the region’s most iconic species, an international team of researchers has found.

Specifically, if greenhouse gas emissions remain unchecked, “then it is highly likely that we’ll lose every polar bear population in the world before the end of the century,” said Peter Molnar, a researcher in global change ecology at the University of Toronto and lead author of a new study that tracks the bears’ fate through time under different emissions scenarios.

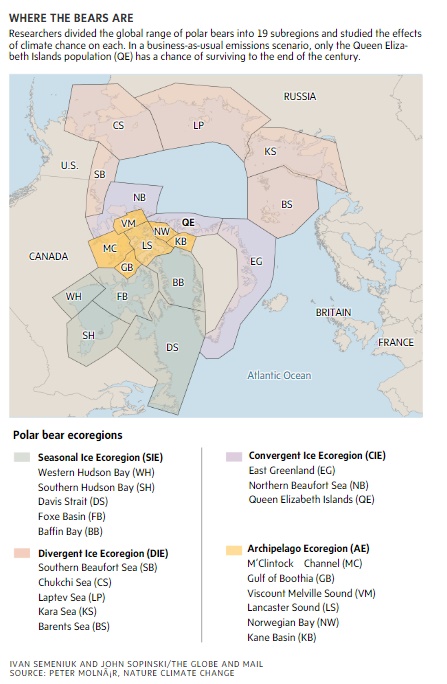

Only one out of 19 polar bear populations identified by the study has a chance at surviving a business-as-usual trajectory, Dr. Molnar said. A vestigial group could still be holding out 80 years from now on the Queen Elizabeth Islands, on the northwest fringe of Canada’s Arctic archipelago.

Alternatively, in an intermediate climate scenario in which carbon emissions peak and then drop after 2040, polar bear populations will experience significant stress at the southern edge of their current range, but the more northerly populations “have a good chance of persisting,” Dr. Molnar said.

While it’s long been known that polar bears are increasingly at risk as the Arctic warms, the study, published Monday in the journal Nature Climate Change, is the most detailed effort yet to establish when polar bears in different areas are mostly likely to cross nutritional thresholds that could trigger population collapse.

Globally, the size of the polar bear population is difficult to assess, but current estimates range between 21,500 to 25,000, Dr. Molnar said. The study did not attempt to track overall population numbers but instead looked at the future viability of the species by combining what is known about polar-bear physiology with climate models that forecast sea-ice extent across the Arctic Ocean over the rest of the century.

Sea ice is crucial to the bears’ continued survival because the powerful carnivores feed off of seals that must periodically come to the surface at breathing holes that they maintain in the ice.

When faced with open water, polar bears are not able to capture seals. In places where sea ice has disappeared for the summer, bears must fast and live off of their fat stores until they can resume hunting.

For the bears, the question is “how full is your tank before you have to get through this period?” Dr. Molnar said.

In the study, the team looked at the maximum and minimum amount of fat that adult bears can store on their bodies and linked this to the viability of populations in different ecoregions as sea ice diminished and periods of open water increased. At various points, the projections showed different populations crossing thresholds in which starvation and loss of young becomes inevitable.

By about the year 2090 under the business-as-usual emissions scenario, the projections showed even those individual bears that are most capable of gathering and storing fat when food is available will be unable to overcome the challenge of increasingly longer fasting periods.

Dr. Molnar said there are two factors that could cement the polar bears’ fate even sooner. One is natural climate variability, which could lead to a faster disappearance of sea ice than the average indicated by the climate models. In that case, a few warmer-than-average seasons could hasten starvation for many bears. Another is the fact that when sea ice is present but relatively thin and fractured, polar bears must burn more calories manoeuvring through the terrain than they would in places where the ice is stable and forms a supportive surface.

Andrew Derocher, a wildlife biologist at the University of Alberta who was among the first to highlight the threat that climate change poses to polar bears but who was not involved in the new study, said the results expand and refine what was previously known about the problem.

“It also covers a broader geographic area than any other previous work,” he said. “So we’re getting a better global perspective on what the fate of polar bears is likely to be.”

The results highlight the fact that meaningful action on climate change is required in the near term to ensure continued survival of the species. The alternative would require extraordinary measures, such as feeding and maintaining a remnant group of polar bears that may be still lingering in Canada’s far north at the end of the century.

Dr. Derocher added that if carbon emissions continue at their current pace, humanity will be facing so many challenges by then that it seems unlikely that polar bears will be given high priority.

IVAN SEMENIUK

SCIENCE REPORTER

The Globe and Mail, July 20, 2020